The Weekend Australian Magazine story: ‘The Bone Collector: Dr Carl Stephan’, October 2015

A story for the October 24 issue of The Weekend Australian Magazine. Excerpt below.

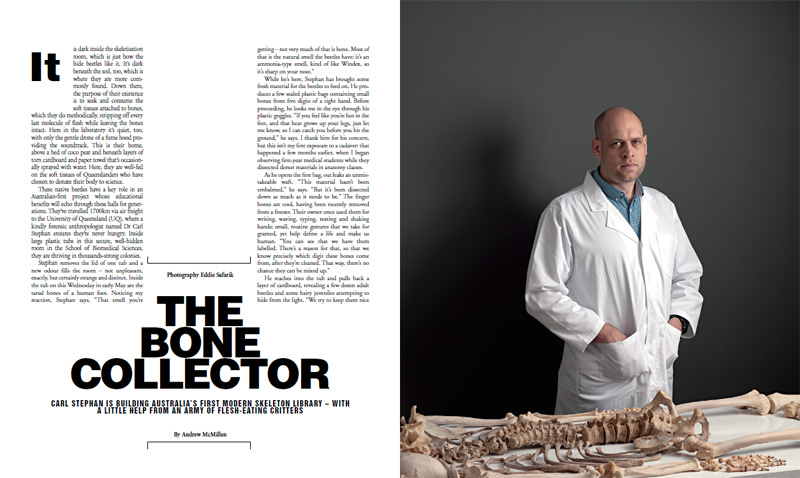

Carl Stephan is building Australia’s first modern skeleton library – with a little help from an army of flesh-eating bugs.

It is dark inside the skeletisation room, which is just how the hide beetles like it. It’s dark beneath the soil, too, which is where they are more commonly found. Down there, the purpose of their existence is to seek and consume the soft tissues attached to bones, which they do methodically, stripping off every last molecule of flesh while leaving the bones intact. Here in the laboratory it’s quiet, too, with only the gentle drone of a fume hood providing the soundtrack. This is their home, above a bed of coco peat and beneath layers of torn cardboard and paper towel that’s occasionally sprayed with water. Here, they are well-fed on the soft tissues of Queenslanders who have chosen to donate their bodies to science.

These native beetles have a key role in an Australian-first project whose educational benefits will echo through these halls for generations. They’ve travelled 1700km via air freight to the University of Queensland, where a kindly forensic anthropologist named Dr Carl Stephan ensures they’re never hungry. Inside large plastic tubs in this secure, well-hidden room in the School of Biomedical Sciences, they are thriving in thousands-strong colonies.

Stephan removes the lid of one tub and a new odour fills the room – not unpleasant, exactly, but certainly strange and distinct. Inside the tub on this Wednesday in early May are the tarsal bones of a human foot. Noticing my reaction, Stephan says, “That smell you’re getting – not very much of that is bone. Most of that is the natural smell the beetles have: it’s an ammonia-type smell, kind of like Windex, so it’s sharp on your nose.”

While he’s here, Stephan has brought some fresh material for the beetles to feed on. He produces a few sealed plastic bags containing small bones from five digits of a right hand. Before proceeding, he looks me in the eye through his plastic goggles. “If you feel like you’re hot in the feet, and that heat grows up your legs, just let me know, so I can catch you before you hit the ground,” he says. I thank him for his concern, but this isn’t my first exposure to a cadaver: that happened a few months earlier, when I began observing first-year medical students while they dissected donor materials in anatomy classes.

As he opens the first bag, out leaks an unmistakeable waft. “This material hasn’t been embalmed,” he says. “But it’s been dissected down as much as it needs to be.” The finger bones are cool, having been recently removed from a freezer. Their owner once used them for writing, waving, typing, texting and shaking hands; small, routine gestures that we take for granted, yet help define a life and make us human. “You can see that we have them labelled. There’s a reason for that, so that we know precisely which digit these bones come from, after they’re cleaned. That way, there’s no chance they can be mixed up.”

He reaches into the tub and pulls back a layer of cardboard, revealing a few dozen adult beetles and some hairy juveniles attempting to hide from the light. “We try to keep them nice and healthy, and happy,” he says with a smile. He gently places the new bones beneath the cardboard and closes the lid.

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: Eddie Safarik.