Bite Magazine story: ‘Here To Help: Refugee dentist Dr Hooman Baghaie’, September 2017

A cover story for the September 2017 issue of Bite, a magazine for Australian dentists. Excerpt below.

In high-achieving refugee dentist Dr Hooman Baghaie, Iran’s loss is Australia’s gain

When he was 12 years old, Dr Hooman Baghaie’s family left their comfortable, middle-class life in Iran behind. This decision by his parents was made out of love and sacrifice: as members of a religious minority, they had experienced discrimination and persecution. The last slight was when their eldest son was denied entry to a college for gifted children after his father, Zia, had volunteered to the school’s administration that the family were followers of the Bahá’í faith. Suddenly, Hooman’s academic gifts were seen in a different light.

There was no place for Hooman there, his parents were told, despite his excellent results on the entry exam. Nor was there a place in Iran for the Baghaie family, who had tired of this persecution. They knew there would only be more hurdles for their bright children in Iran, and they knew that other Bahá’ís had been jailed because of their religious affiliations. The eldest son’s rejection mirrored an earlier disappointment experienced by his mother, Betsy, who was expelled from medical school in 1988 on the basis of her faith. Like mother, like son.

Yet it was in thumbing through her copy of Gray’s Anatomy that the seed for Hooman’s career was planted. Within a decade, the Iranian-born refugee would be safe and secure in Australia while immersed in studying oral health, and later dentistry, while on a path to fulfil the inclusive, community-minded spirit on which his faith was based.

The family’s path to Australia was not simple or easy. They left behind two houses, two cars and his father’s well-established career in refrigeration engineering. The five of them—Zia, Betsy, Hooman and his two younger sisters, Helya and Hasti—spent nine months in limbo at an apartment in Kayseri, Turkey. They were asylum seekers, and on arrival, Zia went to the United Nations office to explain their situation. After carefully reviewing their case and confirming the truth of their allegations, the Baghaie family were awarded humanitarian visas to Australia, since Betsy had family members who lived in Geelong.

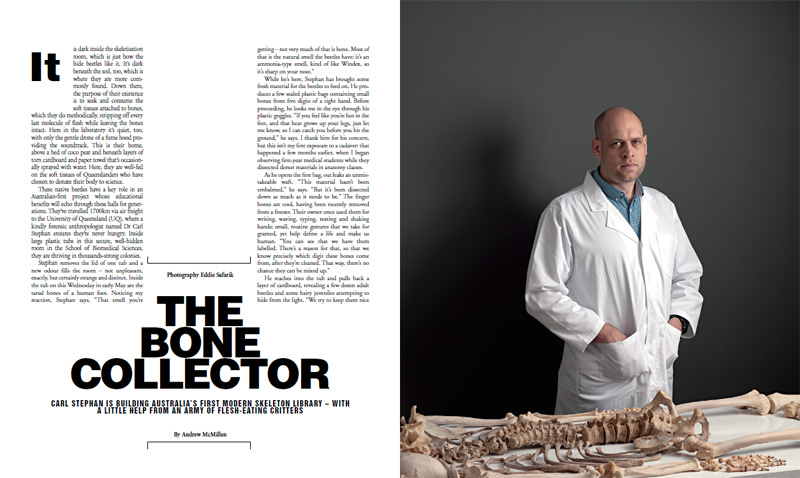

Now 26 and living on the Gold Coast, Hooman Baghaie tells this story over cups of Persian tea and a plate of walnut biscuits. He lives in a high-rise apartment building in Southport that overlooks the ocean, and each morning, his bedroom is lit by a spectacular sunrise. Two days per week, he works as a dentist at a small clinic in Helensvale; during the remaining weekdays, he attends nearby Griffith University while studying his first year of a degree in medicine.

His interest in the oral cavity has widened since he completed a Bachelor of Oral Health at the University of Melbourne in 2011, then moved north to dedicate himself to a Bachelor of Dental Science, which he completed in 2016 as a valedictorian at the University of Queensland. After medicine, he plans to specialise in maxillofacial surgery.

Newly married in 2017, Hooman shares the Southport apartment with his wife, Maya, who works as a nutritionist. The pair share their Bahá’í faith and are devoted to fulfilling its tenet of improving the lives of others: she by advising people on their diet, and he by tending to their oral health needs. Theirs is a service-oriented partnership that looks outward, and asks: how can we help?

To read the full story, visit Bite Magazine. Above photo credit: Richard Whitfield.