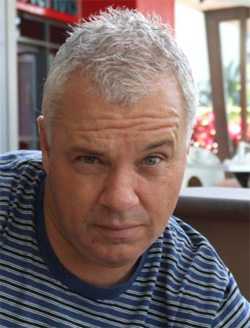

A Conversation With Matthew Condon, Brisbane-based author and journalist

I met with Brisbane-based author and journalist Matthew Condon [pictured right] in late June 2010, to discuss his newest book, Brisbane, for a profile in The Weekend Australian Review. You can read that story here.

I met with Brisbane-based author and journalist Matthew Condon [pictured right] in late June 2010, to discuss his newest book, Brisbane, for a profile in The Weekend Australian Review. You can read that story here.

Full transcript of our conversation is below. As mentioned elsewhere, this was a particularly enjoyable interview, as Matthew is one of my favourite feature writers – I hold his work for The Courier-Mail’s QWeekend magazine in high regard. Brisbane is a great read, too.

Beware: for those who haven’t read Brisbane, there are spoilers.

++

Andrew: I read your book yesterday.

Matthew: Right.

To give you a bit of my background, I grew up in Bundaberg, then came to Brisbane for university in 2006. Although my father’s from Brisbane, I’ve not paid a lot of attention to Brisbane’s history, so I did find it quite an educational experience. I liked the way that you blended it alongside your stories from growing up in this city.

Obviously, I had to include the history, but I wanted the book to move back and forth in time to try and get that effect of – ‘is the past still in the present?’, and so I structured it in that way, no chapters, that it would just meander, and that the present and past would constantly chafe against each other. There were little thematic links; I tried to stitch it through and run a few parallel narratives so that at least rather than a dreary history of a city, that it would have at least a few narrative lines that would pull people through it.

It definitely had a narrative arc, from your experiences as a child through to you telling your children about the history of Brisbane, and them asking questions.

That was organic, really, as the book grew. It was interesting how that line of it sort of came to the surface. I didn’t have an intention to write a book about children; however, maybe writing about Brisbane and my childhood is looking for the child that I was, and then seeing it perhaps in my children.

So, in a way, that too is the shimmering of the past and the present, which I think is unique. Ironically, even though we have very little historical buildings, my point of the narrative line of F.W.S. Cumbrae-Stewart and the monument was this; what does it say generationally about the people of the city that really aren’t that fussed with historical accuracy? What does it mean, and does it flow through?

Even though we had very few historical monuments left in terms of buildings and treasuring our historical sites, it’s still weirdly a city where the past is always somehow present to me. This is just my view, but is that nostalgia? Maybe it is. I don’t know. It’s a city that I think most Brisbane people who go away and come back, it’s a city that puts its claws into your heart, funnily enough.

The recurring metaphor you use, a ‘book without an index’, seems quite apt.

Yeah, a lot of people will get upset with that but I think it’s very true. When I went to look for my relatives in Toowong Cemetery, I’ve since been in touch with them and they’ve said “you can always come to the office and we’ll guide you,” but the point is if you want to wander in and visit your antecedents, it’s a very difficult thing to do. You wouldn’t think it would be that hard.

So to me, the cemetery in the end of the book became a microcosm of this entire city. Funnily enough, topographically, it’s sort of a miniature – it’s the leaders on the hills, the rest of us are down in the valleys, which is very much as Brisbane is now. The ridges are either populated by the church, or the wealthy, and that’s a paradigm that replicates itself in cities across the world. It’s not just Brisbane.

So what was the brief you received for this book? How did Phillipa [McGuinness, New South books’ commissioning editor] bring it to you?

The brief was probably the singular most simplistic, liberating brief that I’ve ever received. She just said “Look, you do Brisbane and approach it the way you wish,” which on one hand is brilliant. On the other, when you come down to practically writing, when you come down to trying to put your arms around an entire city, it was very difficult. It sounded great.

The task was very difficult because I had deliberated for months and months, how does one write and capture a city? How do you go about it? Then I decided it’s impossible, it really is impossible to do it thoroughly. It would be endless. The city is organic. It’s constantly shifting and changing, so I had to not be afraid of giving myself limitations, that it would be my personal view, and after months and months of deliberating and thinking the usual; does one do it by the seasons, or to give yourself this sort of predictable structure?

And then I tossed all of them through my mind and one day I just decided “Look, I’m going to go to where X marks the spot, where Oxley came ashore. That’s the Caucasian history of the city. I’ll start there, and I’ll see where it takes me.” I did that.

One day I just put a notebook in a bag and a camera, and I went down to North Quay, to the dreary granite monument, and I’d never stood before it. I’d seen it a million times, all through my life, and as I wrote. So I stood there with the traffic roaring on both sides, and something about it… [laughs] I don’t know what it was, something about it struck me as wrong. The wording was sort of hesitant. It didn’t feel right. So I thought, “Okay, this is where I start. I’ll investigate the monument.” And that kicked the journey off, really.

I liked how you brought your investigative journalism with Qweekend into the mix. That’s probably what influenced Phillipa in asking you to do it, in that you’d been writing in and around Brisbane since you returned.

That’s a really good point, because I only realised halfway through the book how important it had been to be doing that journalism for five years, and how in fact I’d touched on many, many things across the city – both contemporary and historical – and I wasn’t as removed from it as I actually thought that I was.

That’s a really good point, because I only realised halfway through the book how important it had been to be doing that journalism for five years, and how in fact I’d touched on many, many things across the city – both contemporary and historical – and I wasn’t as removed from it as I actually thought that I was.

I looked at this book personally as a way of trying to write my way back into the city. When I came back, I felt I knew it was the city I’d been born in. In those first couple of years, I’d drive past my childhood house several times. It was me trying to reconnect with a city that I’d lost touch with for 18-odd years. And something deep inside of me told me to do this book, because perhaps it would embed me back into Brisbane. In many ways, it did that.

It required me to concentrate on the geography, the landscape, where I was living, and to open my eyes, basically. So, it served a very important personal purpose for me. Doing the book made me feel more comfortable and relaxed here now, and at home, in a sense.

And along the way you did touch upon some personal experiences, like finding that film canister in your great grandfather’s darkroom.

Yeah; that’s a story from when I was about 12, and it just fitted into this book, in terms of me searching for evidence of myself and hopefully the wider populace of my generation in particular. You’re of a different generation, but as I’d mentioned in the book; when one leaves a city like Brisbane, the longer you’re away, the more the city that it was to you calcifies in your mind, and becomes fixed as ‘Brisbane the city’, your home city. But cities move on. People grow older, things happen, buildings get torn down, landscapes change, cultures change. Brisbane’s culture is phenomenally, vastly different from when I left.

When you come back you’re shocked. It’s not what you thought it was, because you’ve sort of fairytale’d it in your head. I realised only after I’d written it and read through it that the book is a partial examination of memory and the function of memory.

Indeed as you’ve noted, at the end of the book I test my memories against living contemporary people in my life. They say “No, that didn’t happen, that’s not here, no.” So it’s an examination of memory and how we fictionalise ourselves, so there’s that game playing in the book as well.

When that part came up, it was a real shock because it was almost like breaking the fourth wall, I suppose, to say “So this is what I’ve written, but these parts might be false. These might not have happened.”

Exactly, and it’s sort of a spring that unloads in the book, I think. And, when I wrote that little section, it’s not huge, I was trying to be as honest as I humanly could. Maybe I am wrong. Maybe all of that memory I have has altered, changed, mutated over 20 or 30 years. Maybe that’s what we do with memory, we fit it to suit ourselves, and we reinvent lines of family life and history. How do we do that? Why do we do that? Why does that happen?

Maybe it’s like the monument in that we ultimately end up believing that’s really where Oxley came ashore, even though in the back of our mind we know it’s wrong. So maybe that’s a sort of human trait that is obvious to most people, but it’s just something that grew as part of the investigation, and the journey through the book.

I wanted the book to represent a journey as well, because it was a journey for me. It was while I had young children and all of that was kicking in, and looking at my son; he stars in the book to some degree. There were moments when I’d look at him and go “That’s me. I’m time travelling here.” Some things that he would do, I did that, precisely.

And so there’s a way we can travel through time in that sense and I wanted to try, whether it’s even humanly possible to replicate that in literature I don’t know, but I was trying to do that, as best as I could to enunciate the passage of time, which has always been funnily enough a preoccupation with my work. Now that I’m older and have written several things, I see now… you see a recurrent theme. Now, there’s a primary theme.

I like how you dwelled upon the issue of time in Brisbane, centuries ago, when there was no one clock that told the time, and it was driving people crazy.

[laughs] It’s always been a city that has an uncomfortable relationship with time I think. [laughs] I really do think that. To others, for decades, we were always seen as “behind the times” and you know; that’s a part of the fabric of this town, really.

I like the way that you segued into the city hall and the clock tower discussion, how you and your son were sitting in your home and you heard the bell chime from city hall.

Yeah, and that’s happened a few times since. I was just sitting there with my son. I remember my grandmother lives not far, around the corner from where I live now in Paddington, and I remember sitting on the back step of her tiny little old Queenslander and you could hear the clock. To hear it again, through the business of a modern metropolis, raised the hairs on my neck, basically. That might seem uninteresting and minor to some people but it was like reaching your arm back in time 40 years. It was creepy.

And little things like that happened. When writers are doing a book they often go “Oh there was an incredible coincidence while I was writing the book, this happened.” I’ve had that for several books, that things – you go “That’s perfect for my book! I can’t believe that just happened.”

But I think when you’re working on a project, your antennae are so sensitised to what you’re doing that things come in and you notice things specific to your project. You’re more attentive to everything, and sensitive to everything. And they’re not coincidences; it’s just that you have a heightened sense of appreciation when you’re embedded in a project like that. That’s sort of what happened with this book when my son and I were down at the park opposite Suncorp [Stadium, Milton], as I wrote in the book.

I’d just been researching how that was the first major cemetery for the city, and that day after it had rained and he said “Daddy, it smells like skeletons,” and that’s a direct quote from him. I thought “Wow, I can use that!” [laughs]

I hope your son appreciates how much of a star he is in the book when he reads it.

At the moment he’s reading about dinosaurs and spiders, but he may. He narrated to me his first short story the other night. He’s almost five. It was called “The Mantis in the Plane by the Sea”. And so I transcribe it and read it out for him so that one day he might look at that and go “Wow, that’s interesting.” I guess I’m quite a sentimental person, human being as well. I’ll keep them; whether he addresses or not is not important, but I’ll keep them for him.

Phillipa tells me that the series was pitched as “travel books when no one leaves home,” but you’re a bit of an anomaly to the book process because you did leave for the middle part of your life so far. I don’t necessarily think that’s a bad thing because it allows you to step away and describe and outsider’s perspective of Brisbane and how you felt upon leaving and upon returning.

Exactly. I think I was in a unique position, having been born here, and left for important years of my life to come back and see this demonstrable change. On one level, yes, enormous change, but as I’ve tried to portray in the book, a constancy running underneath as well. The Brisbane light, the feel, the weather, the lushness, the vegetation – that’s the same as when I was a kid. Other things change around it and I think to get that perspective was unique in the sense that I did have that time lapse, came back to it with fresh eyes, I guess, and it may have been a very different book if it had been written by a writer who had stayed here.

Exactly. I think I was in a unique position, having been born here, and left for important years of my life to come back and see this demonstrable change. On one level, yes, enormous change, but as I’ve tried to portray in the book, a constancy running underneath as well. The Brisbane light, the feel, the weather, the lushness, the vegetation – that’s the same as when I was a kid. Other things change around it and I think to get that perspective was unique in the sense that I did have that time lapse, came back to it with fresh eyes, I guess, and it may have been a very different book if it had been written by a writer who had stayed here.

I tried to give it justice and to give it fairness. If I’m a critic of the city, I’ve tried to balance it as I would my journalism, or whatever. But there may be some things in there that Brisbane people disagree with or are offended by. That’s great. That’s indicative of a grown up city. We should be debating, questioning ourselves, tilling the soil, and asking these things of each other because that’s what a civilised community is.

I do point out in the book that my supposition is that there are some traits that are in Brisbane people, have been from the start because of the nature of our birth, white birth; it was a very aggressive city, violent. There was death, crime and punishment just over the river there not far from the executive building that the current Premier sits. That’s where the convicts were flogged on the A-frame, the short walk to the Premier’s office 200 years later. Things change enormously, but sometimes they don’t change that much, at the same time.

So, our relationship with Sydney and the colony of New South Wales is always aggressive and we always felt we were poorly treated by them, and so a chip on our shoulder evolved from that. I think if you look and listen carefully enough, we still have some of that. The ghost of that is still around. While I think we’ve moved into the 21st century to a large degree, there are those beautiful generational traits that only your place can give you and I think we still have them. I tried to examine that, but that may ruffle some peoples’ feathers and it may not. I just tried to be honest.

It wasn’t overwhelming, but there was I feel a recurring theme of romanticism that you brought to your experiences in Brisbane, how you said you “keep coming back to the light of Brisbane,” and you describe how that tends to bring people in. That’s “the first thing they notice when they get off the tram,” and so forth. Did you realise that before you started writing it?

I think I did because when I moved away, Brisbane was always my home. It was always where I was born, the place on the planet where I was born. It does have distinct, peculiar characteristics that delineate it from other cities in the world, let alone Australia. And [David] Malouf has written about this, Rodney Hall and others have written about this. They write about it because it’s very true.

The greatest, strongest memories of my childhood are the light, and the pitch blackness of the shadows, and that’s different when you live in other places in the world. It’s distinctively different. The smell, and in summer when a violent storm comes over the ranges, and the steam comes off the bitumen and the plants are breathing out, it’s unique to the city and it strikes you as something new every time. “Oh wow, that’s Brisbane.”

And it’s something that you keep very deep inside of you, I think. I’m a lot older than you. The older you get, these things are like little drawers inside of your person, and nothing will change them.

That may be romantic, that may be nostalgic, but as I said to you earlier; this is a city that from my own experience prompts sort of nostalgia and as a birth place, loss of heritage, mistreatment of the landscape and heritage; as a Brisbane person I feel that very keenly the way the Sydney people probably do about their own environment. This was where I came into the world. Nothing’s going to change that.

This is not so much a question as a comment; when I interviewed John Birmingham the other day, I asked him to comment on the divide between popular fiction and literary fiction. He brought up that he thinks you are one of the finest literary fiction writers in Australia.

God bless him. I’ll have him stuffed and mounted. [laughs]

This was without even mentioning that I was interviewing you for this book. He just came upon that. I thought that was a nice little turnaround.

I’ve known John for years and some of the old dudes are coming back home: artists, painters, writers, musicians, actors. It’s was a very different place when we left. It was very claustrophobic. I won’t say it was parochial… there was an element of parochialism, to be honest with you, but the politics was suffocating, all of that. The assumption, right or wrong, was that “if I’m going to make it I can’t make it here”.

Twenty-five years later you can be in Brisbane and be making it [like you would] in London or New York or Berlin. Everything has changed, and the city has changed too as well, clearly, but the imperative to leave I don’t think any longer exists. We were sort of refugees for a reason that’s no longer here.

Why do we come back? There’s a myriad of reasons for that. I just got tired of Sydney and it just became very hard to live daily. I was freelancing and doing all of that. Where do you go in that circumstance? You drift home and see what happens. Then my partner – now wife – fell pregnant, and now I’ve got two children, and it sort of becomes home again.

I wonder whether this project was more gratifying for you than your fiction work.

It’s very different. I found it exhilarating but very difficult in the respect that I’m not an historian. There are some brilliant historians in Brisbane that have combed the soil over, and over, and over; there virtually wasn’t a corner I could look into that hadn’t been effectively and interestingly covered by a gaggle of local historians. The city has been documented quite well, but I don’t know how they do it, historians.

The freedom of fiction, to me, is so much more pleasurable. That element is part of my journalistic work too. Obviously, I deal with fact every day and I wanted a book that was not mired in dreary history and it wasn’t a history book. But I would hope that someone visiting the city would pick it up and go “I didn’t know that about this place,” get a feel for the city, rather than a raft of facts.

I don’t know how you’ll feel about this, but upon finishing the book; I thought it’d be great and very apt to see that book start appearing on high school recommended reading lists.

I’d be very happy for that to happen! [laughs].

Because as you said, it’s not a dry, factual, historical piece. It mires in your personal life as well, which I feel is more important than ever for the next generation of Brisbane residents to come across.

That’s a really nice idea.

Just to elaborate on what I was saying then; I hope the book gives people a sense of what the city has been like, and what it’s like to live here. I would hope that it gives them that deep connection to their heart, rather than just their head. That’s a huge ambition for a little book. That was underplaying everything that I was trying to do with this piece of work. Whether I achieved it or not, it’s a big question, but that was my aim to do that. The other important element, too, is that I was really loath to actually write about my own life here, because in all honesty it was quite dreary; suburban, unremarkable.

Yet you made it sound remarkable.

I thought, “How am I going to do this?” I didn’t want to be self-indulgent or dull, and then I thought “I’ll employ a fictional technique, and just look at a boy in Brisbane.” That boy is largely based on me. The minute I stood back from that boy, all the details, fine details, the smells, the senses, everything came in. If I’d written just about myself, and I started to do it, it died on the page. When I stood back and looked at myself as a novelist and journalist, and looked back at this separate figure, everything unlocked. All these memories and things that I hadn’t thought about since I was five years old rushed in.

So that’s the liberation of using a fictional technique on fact. It was a really interesting process for me as a writer to do that. I’d played around with it. “Should I try it, should I not?” The minute I started doing it – bang. It just bloomed.

Many elements of this book were a journey for me, in writing, in memory, in trying to get back to what the city meant to me, what it is now. In many ways, when I finished it, I wasn’t quite sure what I actually had. There were so many new paths I was taking in this little book, so in that sense it was a very gratifying project that gave me more than I had imagined when I first agreed to do the commission.

I think [the City series] is a terrific idea, which has been done loosely in the northern hemisphere. I found it a really interesting and obvious idea. I was surprised no one has actually ever done it, but we would get writers to do the major cities of the country, so as a series project it was very attractive. But yeah, that was the trip.

Phillipa tells me that when she read the book, she was struck by your love for Brisbane. It really shone through, and I agree with her summary, the way it flows from the character as a child through to standing in the cemetery; it’s quite beautiful.

Thank you. It’s a recognition that one is mortal… [laughs] And that the next wave [of children] is out there. I’ll always love Brisbane. There are things I hate about it, there are things that annoy me, that frustrate me but that’s like any resident I guess in any city. But since coming back, it’s given me a lot as well, I think. It’s been wonderful to come home with my own kids and I may move from the city; I don’t know. Who knows? I’m not saying I’ll be here forever, but yeah it’s been a very pleasurable reacquaintance.

As an extension of Philipa’s comment, do you think it’s fair to say that it’s a kind of love letter to Brisbane?

Yeah, in the way that some love letters are raw and honest, can be confusing and upsetting, but if it’s a love letter, its heart is in the right place. I agree. It’s a nice phrase. At the end of the book, I pay homage to many writers. Several of them aren’t quoted in the book but I felt it was important to say thank you to all of those others that have written beautiful stuff about this place.

Gerard Lee, when I was young, when I read his novels, what I understood from that was I could write about Brisbane and it’s okay. That was a vital breakthrough for me. When I was at university in my late teens I read him and thought, “We can do this.” When I read Thea Astley’s It’s Raining In Mango and all of those, I thought, “I can write here. This is going to work. I can do it.” And so they were vitally important to me. The great Peter Porter, [David] Maluof… So I hope this adds another page to that homage to a place, and others will do it again.

My son might do it!

That’d be nice.

That’d be interesting. God save him! [laughs]

++

I highly recommend ordering Matthew Condon’s Brisbane through the publisher, NewSouth.

I liked this interview. I have just finished reading Condon’s earlier work The Motor Cycle Cafe and so I am now reading what I can about him.

Just wanted to say that the writer mentioned as Jared Lee is actually Gerard Lee.

Cheers

Yolanda

Thanks for clarifying that Yolanda.