A year ago, I wrote the words, “Trent Dalton is the best feature journalist in Australia.”

Absolutely nothing has changed.

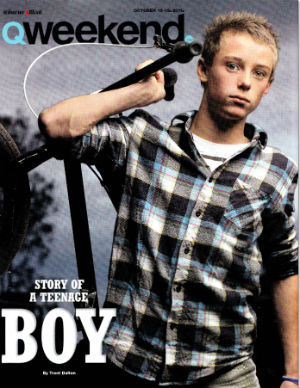

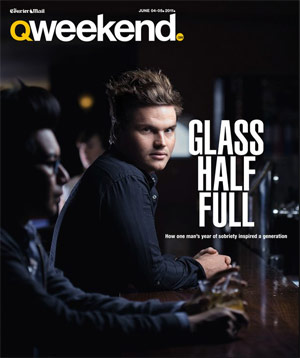

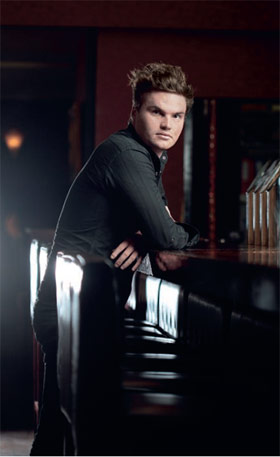

Last Friday, 4 November 2011, Dalton [pictured right] was awarded Features Journalist of the Year at the 2011 News Awards for the second year in a row. (He won the same award in 2008, and was a finalist in 2009 and 2007, too.)

Two months earlier, he was awarded Queensland Journalist of the Year at the Clarion Awards. These accolades are a result of his feature writing for The Courier-Mail‘s Qweekend magazine, where Dalton is a staff writer. He’s also an assistant editor of the newspaper.

Earlier this week, Dalton and I met to discuss a recent pair of Qweekend cover stories over sushi and green tea. Simply named “Story of a Teenage Boy” and “Story of a Teenage Girl“, these features delve deep into the lives of two children who live in Queensland: Casey Tunks, 15, and Chloee Gwynne, 16.

In a way, they’re companion pieces to the last pair of stories I interviewed Dalton about in 2010: “Story of a Man” and “Story of a Woman“.

I highly recommend clicking the below images to read both stories, before moving onto our extensive interview, which was 90 minutes long and runs to 13,000 words. (Clicking the images will open the stories as PDFs in a new window.)

++

Andrew: When we last spoke a year ago, it was just after you were awarded the 2010 News Features Journalist of the Year. This is not really part of why I wanted to interview you today, but – which stories did you put forward this year? I believe “Home is Where the Hurt Is” is one of them.

Trent: Yeah, and also a story called “The Longest Night,” where I spent 24 hours alongside [Queensland premier] Anna Bligh, when Cyclone Yasi was coming in. And then “The Long Goodbye”; lots of ‘longs’ this year! “The Long Goodbye” was about a guy, Scott Sullivan, who is dying of motor neurone disease.

Then five Queensland flood stories, which was where I tracked the up and downs of one particular street n Rosalie [suburb of Brisbane], throughout the whole Brisbane floods; in the days preceding the flood, during the flood, and also afterwards.

And then a story all about kindness, a story where I went around and asked people to share random stories about kind acts they’ve done, or people have done to them.

You were just putting together that kindness story when I interviewed you last time.

That’s right! I had just interviewed a girl who dresses objects in wool. So yeah mate, they’re the ones, those five. They responded mostly to the “Home Is Where the Hurt Is,” the domestic violence one. And Anna Bligh. Oh, they said kind things about all of them but probably mainly that one that really broke through this year, which is great. It’s such an important topic and really close to my heart. It’s a great thing.

Anyway – yeah. I feel like such a dick…

I don’t want to talk about any of those stories. I want to talk about “Story of a Teenage Boy” and “Story of a Teenage Girl”. I want to talk about the mechanics of how you write things, as well as how the stories came to be. We’ll start with – how did you find Casey?

Here’s the brilliance of always hanging out with work-experience people, because they make you seem like you’re a bit nicer than you probably are. It was really a handy thing, that we had this wonderful work-experience girl with us, Rose, who’s just out of high school or university, or something. She was with me on the day and we were just walking around talking to potential people who could be the teenager. We were walking through Queen Street Mall.

It was very difficult to find in the sense that I had to find someone who… maybe a lot of kids might be up for it, but then you had to convince their parents. Basically I said, “I want to do this story where I spend time with you, and you share with me every last thing that’s on your mind, your hopes and fears, your dreams and your worries, and what drives you, and where you want to be, and what’s it like to be a teenager.”

Eventually, after asking several people, this amazing guy Casey said, “Yeah, I’ll do it,” and I said, “I’ve got to ask your mum,” because he was 15. Then he said, “No worries. Here’s my number.” I called his mum and thankfully she had read “Story of A Man” and “Story of a Woman” and she knew I wasn’t a complete crackpot, and that I was trying to do something worthwhile and something that would hopefully give some insight to people, and be done in the sort of way that won’t be exploitative or going to be a horrible experience for the family.

She said “yes”, and so from there we spent all this time together. The mum welcomed me into her home, basically, and said, “Yeah, you can come around at 6am and watch as our family has breakfast, and be there just documenting in the corner what people do.” [laughs]

Is that weird?

Well yes, it is, but I’ll tell you about my next big… I’m very excited… no, I won’t let it out of the bag. What I just said leads into that idea of the anthropological study really driving where I want to… hopefully, the story I want to do next, which is going to be really exciting.

We’ll talk about Casey to start with. You start the story by saying “he’s afraid of two things”, and then you list a bunch of his traits and characteristics. Was that the first intro you came up with, or did you try a few things?

No, these sorts of stories in particular have always been riffing on a whole bunch of intros. I don’t normally spend that much time but these ones I really spent a lot of time on. I don’t think that was my first. I knew I wanted to get in there something about his fears, so hopefully the reader would be mums and dads; looking at the readership going, “Well, the readership is going to be these certain types of people.” You want to get them in, hopefully, by saying something like, “here is an insight into what fear a teenage kid in Queensland might be feeling”.

But I think I was going to go with more of a “here we are”-type thing; something that detailed, gave context, some contextual sort of introduction. Something about the smell of his room; everyone can connect with the smell of a teenager’s room, and that sort of thing, and the fact that it was 6am so we’re basically waking up with this kid. Then I thought, “no, let’s get to the heart of it really quickly.”

And that whole line was just all about the livewire brains of a teenager. “Man, I’m really scared of spiders, but I’m also really scared about my future,” this big thing. “I’m only scared of spiders and my future” – yeah, right. Fucking massive, ‘the future’, that’s what it was all about. It was also trying to be empathetic as well, sort of saying, “I’m with you man, because the future scares me as well, it scares everybody.” It probably scares a teenager even more.

That’s why I chose that. Then that leads into all those traits, a throwback to the style of “Story of a Man,” “Story of a Woman” which was all just… these ones were much more “this happened, and then this happened”. But the “Story of a Man” and “Story of a Woman” were really just all about their character. I was really trying to tap into, or get a bit of the guy’s character.

That’s classic screenwriting sort of stuff. The first 15 minutes of the film will offer you a little insight into your character so you know either you’re really rooting for this character, or you’ve already worked out their… you don’t like the character or you do, but either way you’ve invested some sort of emotion in him pretty early. That was the idea about writing all those traits.

I sound like a wanker. I feel like a dick talking about my stupid magazine story.

You’re not allowed to say that anymore, because this whole thing is about you. Relax!

[laughs]

I’m not sure if it happened this way, but the way this story appears, you’re spending a Saturday with Casey. Why a Saturday, as opposed to a school day?

As you know, getting access to schools is really difficult. It could have been done, but I just knew I wasn’t going to get the access to him that I needed for the piece if I had done it on a Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday because it was just going to be… “okay, he gets up, goes to school.” It would have been great if I could have sat in the classes right with him and been right next door to him every time, but I think that would have made him a bit uncomfortable, as well as I couldn’t imagine the Queensland Government giving me the okay. I would have had to have written probably 300 emails that would have gone back and forth to allow that to happen.

In the end, it was a matter of speaking to his mum and saying, “Look, can I just hang out on a Saturday?” when a kid actually does do stuff. Like you know the school day goes from… school’s very interesting. That’s another whole world I’d love to explore one day, but that Saturday; all I said was, “is there a time in the near future when you’re doing something with your friends?” He just went “Yeah, two Saturdays from now we’re all going to the mall.” I went “Okay great, that’ll be perfect,” and then we’ll just track that from start to finish.

Then also one or two catch-ups around that, so you get to know him as well, but then focusing on that day, if that makes sense, using a couple of different days, and sort of knowing the guy. We had a good discussion when we first caught up, but then I realised this was going to be the day; ‘showtime day’. As it turned out, he had a fairly interesting day, for him, coming from Wamuran [a town near Caboolture].

He doesn’t always go into the city, certainly not as much as the girl did. It was a pretty big thing him and his mates going to the city… well, not a big thing, but maybe a once-in-a-month thing. That’s how it came to be on a Saturday. And just the given thing that his parents would be home as well. His dad usually worked, but it just worked out pretty well on a Saturday. People are a bit freer and fun. Weekend work is always really good because everyone is appreciative of the fact that everyone’s out on their weekend, and just a bit more relaxed.

You’ve got a few good lines about his mum in there. “She lets him know she loves him by telling him she loves him.” That’s a fucking great line. There’s also a line about, “she loves him so much that whenever she thinks of seeing his face for the first time, she bursts into tears”. That’s really nice.

Yeah, and I guess that all just comes from, again, the beauty of arriving somewhere at 6am, and you’re there. Can you imagine a kitchen in those early hours? A mum in a kitchen; it’s just a really safe space. It’s a beautiful spot to have a chat to any mum. So you’re there and she’s just in her own kitchen. She’s thinking about her boy. It’s a really wonderful place, and then she gets teary when she mentions him.

A question I’ll often ask people, “Do you remember the first time you saw his face?” That’s always an emotional space to go to. It’s a beautiful thing to talk about. I remember the first time I saw my kids’ faces. I’m sure it was going to be the same for her, and then that was a beautiful moment.

Then you’re just getting the insight into the deep, deep love that she has for this boy. Then he comes out [of his room], and he’s just this 15, 16-year old boy who’s just a knockabout sort of guy. She’s in this space of “he’s an angel,” so it’s a really great thing to see. That wonderful thing that a teenager has no idea how much their parents are just totally in love with them, and just worship them. They have no concept of that. I mean, they have a concept of it but it was just perfect. In this kitchen she had tears in her eyes, and he’s just going “Oh, they’re all right.” It was just great juxtaposition.

His father Warren gave you and Casey a lift to the train station. You glossed over that a bit in the story. Was there a reason behind that?

There just wasn’t much happening, for one thing. It was probably a lot more talk about practicalities, like, “Have you got my number in your phone?” and all that sort of stuff. I guess it’s also timeframes. [pause] A lot happened in that conversation that maybe came out later on in the piece. You go with trying to take the most important things.

It was partly on that trip that Casey started talking about this time he came home drunk, and I think it was sort of a sensitive area. I was consciously trying not to make his parents look like they’d ever done anything wrong. I can’t even remember what was exactly said in that conversation, but it was more riffing on their sort of fear, their terror, at seeing their son come home pissed, and then he passed out.

It was glossed over, and you could write about a 4,000 word story on any father and son, taking a trip somewhere. I think I probably should have, but it was more I wanted to get to those friends pretty quickly, and really keep it about Casey, not so much be a father-and-son relationship. I don’t know, but Warren was cool.

He didn’t really know what I was about, just going, “What? Why the hell are you following my son around?” I’m sitting in the backseat of his car taking notes. [laughs] He’s this earthmover, sort of ‘tough dad’ type guy. He’s driving his son, this really great loving father, just trying to get the best for his son. He was constantly befuddled at why this journo would want to do it.

The mum really understood and was like, “Yeah, I can see,” because she had read those pieces she was like, “I know exactly where you’re coming from.” As has been the case with these, there’s great trepidation there, but they always say, “I think what you’re trying to do is probably worthy, or worth it if it adds national insight into our teenagers”. I think that’s where the mum and dad were coming from, and God bless them. They were so wonderful. He was cool, the dad.

In the end, after a while he sort of ignored me, forgot I was there, which was really cool. That was the whole idea, that he’d just be going “All right, back by 2pm,” and he’d go “Yeah, yeah,” and pops out of the car. He maybe gave him a “yes Dad,” and that was it. It was a funny dynamic to see that. There’s probably another great story in there between fathers and sons that I probably should have dwelled on a bit more. Anyway. [laughs]

There’s a lot of Casey’s language in this story. Is that important to you?

Totally. That was the big thing I love about teenagers now, and I’ve always loved about teenagers – they’re creating their own words, and creating their own dialogue, and having their own little language. I think that’s such a special part of being youthful. I think it’s so brilliant and something that we all… I feel like I’m so far removed from, even though I’m 32, but I feel so far removed from all the things that he was saying. I had my own language with my friends at that age, but I thought that was brilliant.

From my anthropological journalism style stuff, this is magic. I kept going, “what does that mean? What’s that?” And also – I couldn’t keep up. My notepad couldn’t keep up. I was just going, “Man, gotta get all this stuff.” It was gold firing out of their lips and I only got probably half of the great stuff. You speak to any teenager, and they’re just invigorated.

Casey and all his friends were just amazing. There were some classic moments I had to leave out because I didn’t want to bring myself into it. But for example, when I turned up at the train station… one of the girls looks me up and down and goes, “Ugh, you soooo need some Vans.” [laughs] It was just stuff like that. Then one of the boys told me that he was going to meet these two girls, Danielle and Beth, so when he introduced me I said, “You must be Beth.” It wasn’t Beth, it was Danielle. She goes, “Are you kidding me? I would never, in my life be called Beth.” I said, “Oh, that’s funny, because that’s my daughter’s name.” [laughs] She was mortified, but it was a great little ice breaker.

No one quite knew what I was doing hanging around this guy. But Casey knew where I was at, and he thought it was kind of cool that he had this guy following around documenting and asking him about every aspect of his life as well. Then in the end the girls found it cool as well, so they were going, “Casey does this,” and, “you’ve got to know this about Casey,” and all that sort of stuff.

On that train trip, you’ve got the old ladies, Bev and Shirley, who are “staring at the group like they might regard a Reeperbahn burlesque show”. Did you consider speaking to them, or were you happy to let them sit in their own world?

Maybe in a different story… like, I’ve been following around Campbell Newman a lot lately for a story I’m doing down the track. Everywhere you go, you have periphery people that you’re constantly asking, “What do you make of Campbell Newman? What do you think about this policy?” With Casey, this was telling his story. Casey doesn’t care what Bev and Shirley think. They’re not even on his radar, and that was partly the point of me not going there. These people, you see them on the train, and they don’t even know, or care.

That’s what I love about it. In the girl’s story in particular… I love her so much in the fact that she does not give a shit. All four kids on that train didn’t give a shit either. They’re just talking loud and they have no concept of, “Gee, I better not talk too loud because Bev and Shirley might …” They were just curious. I kept on looking at them. It was priceless. They had the name tags “Bev,” “Shirley.” Even their names were clichéd. It was brilliant.

They had these amazing outfits like they were going to the races. [laughs] Casey and his friends represented the complete opposite to where they were heading on that train, but yet Casey was in this exciting place, heading into the future. The world’s going past outside, and it was such a great little moment. I just loved that.

[quoting the story] “A look of bewilderment on Bev’s face, as this alien world rushes by in blurs of green and gun-metal grey.”

Cool, man. [laughs] Thanks man! That’s great. Just that whole concept of: Casey’s going one way and not really realising that he’s heading somewhere, he doesn’t know where it’s going. That was the thing about the whole piece, too. A teenager is going somewhere really, really fast, but not really knowing where. That’s really exciting.

Bev and Shirley know exactly where they’re at. That’s beautiful, too, but it was this great thing to have them side by side, these two generations. And Casey and his friends were being so oblivious, to the point where they’d be dancing and singing songs, and throwing out F-bombs, not even realising there were two women over there going, “God, who are these creatures?” That classic generational difference, it was right there.

Where were you? If they were sitting in the four train seats, the four teenagers, where were you sitting?

Where you hop onto a train, turn right, and the first place you sit down; you know, the two-seaters? That one there. Bev and Shirley were diagonally across from them. Casey probably could’ve seen them. Casey had his back turned, but his mate Jade could’ve seen them. He was aware of them, but I guess the two friends, Casey and one of the girls, they were just… it was them probably most of all who were completely oblivious.

That’s what I was doing. I was just there and I was taking notes. They were having the most amazing conversation over an hour’s journey from Caboolture to the city. It was a really great get-to-know-you period, really cover a lot of territory, and get a lot of chatting out of the way, and get to know why they were going into town and who Casey was, and stuff about their teachers, and all that.

The whole point was just being fly-on-the-wall as well, and not probing them too much because, in the end, they are 15-year olds. You don’t want to be going too weird, too in-depth, or giving them a hard time. It was more presenting the reader with this moment, taking it and going, “This is what I saw.” It’s classic, “this is it; this is all I saw. I’m not even commenting. This is just what I saw.”

At different points they do discuss drugs, divorce, and cyber-bullying. Casey said, “I’m not sure why any 15-year old would want to kill themselves”. Did they just come naturally, or were they prompted by you?

No, those were prompted by me. Those sorts of topics aren’t even on their radar. I asked those questions because I knew somewhere along the line, in any sort of conversation with a teenager or in-depth piece on teenage life, you probably should ask those questions. Though I guess parents worry about it more. Honestly, they were almost like, “Man, why are you even asking that?” They’re that cool with themselves, they’re that together, that they were like, “yeah, whatever, drugs.” They were so savvy that it was like yesterday’s news. And the whole suicide thing too, which terrifies me, and cyber-bullying and all that stuff is wrapped up in that whole horrifying end of suicide.

I remember getting all serious and tense, like “Let’s talk about some issues.” And they glossed over the heavier stuff in a matter of 30 seconds. It was like, the stuff that mattered to them was actual grief. Then Casey brought up his mate who died. I guess the whole heaviness of a topic like that led to another interesting place; here’s a young man dealing with the total weirdness of losing a friend. I found that fascinating, how he was dealing with that.

That went to a whole different place as well. It was cool, that whole side of it. All those things were prompted by me. Particularly drugs and suicide; they weren’t even going there. They’re just interesting. They had this complete need for entertainment, in many forms. “Look, there’s a guy there picking his nose with a straw! Great!” And then that filled them up for a bit. [laughs] Then they were bored, then… “Oh man, look at this freakin’ King Kong outfit!” That fills them up for a bit. It was this constant need, like those computer game energy bars of excitement. It would go down, something would happen, and it’d be back up. It was really great to see that.

There’s this line where Casey says, “I just wish mum and dad knew that I was going to be okay.” Was that prompted by you?

No. I thought that was such a great line. That was when we were talking with his mate. It’s so great to have a mate of his around to make him feel comfortable about talking, so he’s not just… it was almost said towards his mate, almost like “Don’t you just wish they knew we were all okay?” I thought that was so great and such a meaningful thing for any parent. You know how we worry. You put so much pressure on them, and so much stuff. You bring so much of your own stuff to [parenting]. I think that’s what he was sort of talking about.

He’s got this super-loving mum who’s constantly telling him, “I love you,” and constantly asking all about his life. But he was just saying, “I just wish she knew I’d be okay, and that everything’s going to be all right.” Basically he was saying, “I’m not going to do anything stupid.” He was almost saying, “I’m not planning on doing anything crazy.” I thought that was a great little moment I wanted to definitely get in there somewhere.

It came up in a conversation about… I remember asking a few times this question, like, “what do you wish your parents knew?”, and maybe that’s where it came out. That sounds like it was prompted. But I think it was in an overall discussion, like, “Sometimes they don’t get you, but what do you wish they knew?” Maybe it’s easier, sometimes, telling a guy with a recorder than it is to tell mum. I don’t know. It was cool, that one.

It’s at this point, where you’re at the photo booth with them, that I first realised that you’re invisible in the piece. You’re not there at all. Now that I think about it, I think that’s the case for “Story of a Man” and “Story of a Woman”, as well – you were invisible.

Yeah.

So that was a conscious choice?

Definitely. I’m the first person to put myself in the piece; I’m the biggest egomaniac frickin’ idiot journo. I don’t know, I hate it about myself that sometimes I go, “I’m going to put myself in here.” But I only do that when I feel like it’s necessary and that it adds something to the piece. This was totally all about them and it was all about being, as you say, invisible, and just seeing these magic moments, going “I’m not here,” and hopefully getting to the point where they feel like I’m not here.

Definitely. I’m the first person to put myself in the piece; I’m the biggest egomaniac frickin’ idiot journo. I don’t know, I hate it about myself that sometimes I go, “I’m going to put myself in here.” But I only do that when I feel like it’s necessary and that it adds something to the piece. This was totally all about them and it was all about being, as you say, invisible, and just seeing these magic moments, going “I’m not here,” and hopefully getting to the point where they feel like I’m not here.

At that photo booth, maybe four hours had passed by that time, and then they really felt like I wasn’t there. I’d gotten boring. “We’re over that, there’s other things, let’s go to photo booth and get some pictures.”

Then this incredible moment happens where they’re talking about, “should we put ‘best friends’ on the caption?” You’re documenting these interactions, and this wonderful moment in any teenager’s life where you’re weighing up your friends. Beth had asked, “should we put ‘best friends?’” I remember that feeling. “Am I your best friend?” I remember that whole concept, that beautiful thing between relationships between teenagers. You never quite know where you stand.

Then Casey, that beautiful kid, I just love that kid so much, he made her feel so good and goes, “hells yeah!” or whatever he said. It was just an amazing response, like “yeah, of course.” Just a brilliant… the wisdom of him knowing what she was trying to ask. But to be so cool about it. It was such a great moment and such a rare thing to see those little moments.

If you just passed by that moment, you’d have no idea what was going on, but the journalist has that… this is the great thing about feature writing. You spend time with these people and understand what’s going on. One little moment becomes huge and can be significant. I thought it was so beautiful. Probably my favourite part of the whole piece, that there.

So you spent that Saturday with him, and there was about a month gap between that time and the school holidays, I think.

Yeah, and that was purely because I felt I wanted to get even just a little bit more insight, just a bit more. I didn’t want to end it in the mall again because I knew the girl one was going to be very mall-centred. I called his mum up again…[laughs] And asked them to go through it all again and we did it. We went back and I went over in the early hours of the morning and spent more time with him.

That’s always the best thing you could ever do – go back. I strongly recommend that. Leisa Scott, who writes for Qweekend, told me that years ago: “always keep going back”. You learn more and more, and then by the time you come back next time they know you even more. Then you see even more insights.

It was great; the best thing I ever did. One of his other best friends had been there, so I was getting even more insights. Even in the meantime, all these things had happened to him. He’d got a girlfriend and he’d had a party. All these things had happened, and it was getting closer towards the end of the year so he’s sort of… I remember in high school, any end-of-year time… he wasn’t even in his senior year, but you’re thinking about where you’re going, or even in grade 11 you might have to start making those decisions about what you’re going to do, and all that sort of stuff.

When I came back, he was a different sort of guy, almost. He was a little bit more weighed down by a few more worries, bizarrely, even in that short timeframe. I really got that feeling. He was answering really honestly. It was so cool to do that, he was going, “I’m worried about…” And then he started… that’s probably my favourite bit in the piece, when he starts talking about, “I think I’m really good at English, you know? I think I could do something in English.” I just thought that was so cool, this kid trying to figure out in his head space, “where am I going,” but also trying to work out that inside him, there’s a whole world of possibility, and trying to grapple with that.

What did you advise him when he said he wanted to go into creative writing? You wrote, “Like any writer worth the title, he’s curious about life and the people around him.”

Yeah, well I had said, “Man, you’ll be brilliant. You’d be amazing. You’ve got enthusiasm, you’ve got drive, and you love words. You’ve got a great nature.” I said, “If you’re thinking about it, you should completely do it.” I totally said, “Whenever you decide to, give me a call at The Courier-Mail,” because he was such a great guy. I basically said, “Yeah, come into the office and I’ll show you around,” or something like that. I was really trying to go, “If you’re thinking about that, go for it and chase your dreams.”

I don’t want to sound like too much of a tosser, but he really mirrored my life in many ways. I grew up in Bracken Ridge, which was not far from Caboolture, where he grew up. It was that idea of, in that sort of world you’re knocking around with mates and stuff. No one’s really ever talking about writing, and things like those sorts of ‘cultural pursuits’. A guy like him, he was still thinking, “I think I could do it,” so I wanted to say, “you could do it, and you could do it really well.”

That really inspired me, from a writer’s perspective. I was so pumped that he was into writing. I was going, “Yeah, you’re really good!” That stuff I said in the piece later on about, “It’s the reason why you’re so good with your friends and you’re so good with those girls; they love you so much because you’re a great listener and you care.” I was just watching this kid. He had all this stuff that makes a great writer and he had time for people. I was like “You should do it.”

I really made a point of even writing that, but also that whole… there’s something great about that and I’ve always loved this in teenage movies and stuff, where someone’s battling with their family history. Maybe there’s a long line of Tunkses who used their hands and worked in trades and stuff like that, and done very well, but he’s sort of going, “Maybe I could step out.” I love that.

It was a hard one to put in where he said, “I hope I don’t just become another Tunks,” because I was worried about writing that and saying would that be an insult to his wonderful family. But I still put it in because it was more of an insight into him saying, “I just want to do something different. I want to become my own man.” I thought that was wonderful to hear a 15-year old kid say that sort of stuff, to be there for those sorts of insights. Cool kid. I’ve really got so much time for him. He’s really a wonderful guy.

Did you ever get to see them de-stressing, with the life jackets and the exercise ball [which they referred to in the story]?

Oh no, I didn’t! That was him and his mate. They’re going, “Man, we do this thing. Now we’re about to do it.” I think it rained. They went out on the go-kart and it started raining or something, and they decided not to do it. They were going to go do it. They were going to go stand there with those life jackets and then the exercise ball comes down and hits them. It would’ve been hilarious. I decided as far as activities go, the go-kart was a much more symbolic sort of thing, about movement and taking chances. I went with that.

He offered to introduce you to his Nanna. Do you think that was a sign of trust for him at that point?

Yeah, definitely. That was when I came through on the second visit. After spending a couple of hours with him that morning, and then him going, “come meet Nanna,” it was totally natural, like when you’re around a mate’s house – especially when you’re in high school – you end up doing all sorts of crazy stuff. You go around someone’s house, you go meet Uncle Joe and then you find yourself in the back of a ute, or whatever.

It just reminded me of a high school visit to a friend’s house. “Oh, let’s go get a go-kart.” “I’ll just go say g’day to Nanna. I guess that you’re with me, so yeah, you come along too.” That was brilliant too, because you get to peel back more and more layers of this guy’s personality, this guy’s life. Seeing this other wonderful side of him that loves his Nanna dearly and she loves him. It was great, really good moment.

And just texture-wise, you constantly want to have all these different people, whether they’re speaking to or not, but just places to go. That’s great in a feature article, different places.

You’ve got this line about going to Warren’s shed where there’s “a calendar showing 12 months of buxom women in togs.” Why did you use the word ‘togs’? That cracked me up when I read that. You hardly ever see ‘togs’, it’s such a Queensland term.

[laughs] I think it was because that’s how I remembered it. I think it hadn’t been taken down since 1987, back when women were wearing a full one-piece tog. Not even so much like a bikini. I don’t know, I think that’s maybe why I said togs, as opposed to… what would you call it?

Swimsuit?

Swimsuit, yeah! Togs… I dunno. It’s such a hokey term isn’t it? [laughs]

Based on what you’ve told me – with the momentum of the piece, and Casey going somewhere, but he doesn’t know where – it feels like you had to end it on the go-kart jump. A freeze-frame picture.

Totally. And what eventually did happen was, he landed heavily. His mate hops in the thing and then we went and rode some horses or something. He got a horse out. But you’ve got to think, “where’s the best, most lyrical, amazing place that says everything?” I really thought hard about that. I thought, “I can, being the writer, end this anywhere I like.” I thought, “well, let’s just take it right up to there.” I thought “Wow, that’s so Casey.” Everything’s up in the air and everything… I thought, symbolically, that was just magic.

I admired him for even doing it. It was insane, what he was doing. I was going, “I shouldn’t even be around for this.” I was just going, “Nah, this is really bad. If something happens here…” There were no adults around at that time, and I remember just thinking, “Nah, this is probably wrong that I should be party to this, that these guys are doing these crazy jumps on this go-kart.” That’s magic, too, and that’s the balls of a teenage kid that I really wanted to get in there as well. It was all about – “man, don’t lose that.”

I was constantly thinking, all the way through, how I’ve probably lost that. I used to do crazy stuff all the time but sadly, you get married, you have kids, and you go, “No, I better not do that crazy thing.”

The end scene is like the great endings of a million different movies. I just loved that; he’s there, mid-air, and the outcome’s his. The rest of the story is only his, like, “we’ve been looking into it, and now we’ve stopped now. I’ve stopped now. The rest is his journey.” That’s what I’m trying to say.

Did he ask you much about the mechanics of your job, or your approach to the story during the whole process?

No. He totally couldn’t care less. It was so funny and so amazing… the girl was even moreso. Particularly with Chloee, it was like “Of course you want to come!” It was that great Gen-Y or Gen… I don’t know, are they still Gen-Y? I don’t know, they’re probably something earlier… but Gen-Y, that great, “Yeah, fuckin’ oath man, cover my life story, great! It’s fascinating, my world’s awesome!” It was like, “I don’t care how you tell it, or what you need from me.” It was just, “Come along for the ride, man, and strap in.” It was really funny.

Even after the story, it took a long time between the story, me actually doing it and then it actually running. It took a long time. Casey didn’t care. I’d call up every now and then and go, “Mate, that story, it’s going to run, the dates got shifted and all this stuff – but it’s going to run.” He was like, “Yeah, whatever, no worries.” He’s just living his life! It’s this heavy thing on my mind, but he couldn’t give a shit. It was brilliant. It was so them, for both of them, they’re like, “yeah, whatever, no worries.” It was funny.

Were you happy with him as a subject? Did he give you enough; could you have asked more?

No I couldn’t have, in terms of… this is the big thing, and I’ll probably tap into this more about the girl, which got a hammering. It got smashed. It copped a pasting. The intention was, whoever said yes [out of the teenagers], just cover it, and that would be it. That is the idea, similar to the way “Story of a Man” and “Story of a Woman” were just about random people. The big thing was, I never wanted it to be like, “Here’s Qweekend, coming along and telling you, the reader, what it is to be a teenager these days.” But what we’re doing is, “here’s this teenager, this one guy, and this is his story. Take from that what you will.” In that sense, he was brilliant, in terms of showing me his life, his story, and giving me access into his life. He was amazing.

He still gave me everything I’d hoped for and more, he was an amazing kid, but as far as what it is to be a teenager, he didn’t really dwell on because he’s almost too cool for that. He was just like “I’m moving so fast, I don’t even have the time to think about what being a teenager means to me.” So the whole process of him was a snapshot, and it was movement and capturing that.

In answer to the question, he totally gave me that and more. He was amazing, but maybe not what other people wanted, like if you’d come to read the story you might go, “Oh, I wanted to know more about what teenagers think about politics,” or all that sort of stuff. With the girl story, a colleague of mine said, “I love that piece you did on the girl, but I wish you did more insight. I wish you sort of showed more of your own analysis,” she said. I was just going, “Yeah, but that wasn’t my intention.” It wasn’t me bringing my thoughts on teenagers, or commenting or judging, or anything like that.

So – the story ran eventually. What kind of feedback did you get from Casey and his family?

Um… [pause]

Have you spoken to them?

Nah, I haven’t. I’ve sent them massive letters, and magazines, and that’s it. They either were…

Shocked?

Or… it happens all the time. You send them the mags, and go, “Thank you so much, and the family moves on.” You just go – that’s it. It’s an interesting sort of discussion. You go, “Do I keep probing them, and asking ‘how’re you going?’” and all that sort of stuff, and take it to the level, or… yeah. So my thing was, “mate, thank you so much.” I wrote this big letter saying, “Give me a call at The Courier-Mail when you graduate,” and all that sort of stuff. We sent him magazines, and did up a disc of images; every photo that we took. We were like, “Okay, we’ll get out of your lives now.” I tend to leave my card, and say, “If you want to call me, please don’t hesitate to call.” But I don’t want to keep hassling them, you know? It’s always a strange sort of thing.

But I should probably… I’d love to catch up with him again. I basically said to him, if he wants to catch up, come in anytime. I’ve left it up to him. It’s an interesting one.

I called Chloee, because I was a bit more worried about her as she revealed a bit more stuff. I called her, and she was really cool, and tough as nails, which is great. But the whole thing, the whole stories never sit easy with me. You’re putting these people’s lives out into a magazine. With Chloee in particular… Casey’s life was pretty straightforward, but Chloee’s was really an eye-opening insight into her life, so that was a whole different story. And also, you call them up to let them know the feedback. I did that with Casey, too. I sent him a whole bunch of feedback from people, saying, “You’re the most amazing, inspiring kid, and you’re parents should be so proud.” That kind of stuff. We make sure we keep all those letters in there.

With Chloee, it was more like – “We’ve had great letters, and we’ve had really bad letters.” My whole thing with her was more to call her up and say, “You are an amazing teenager, and don’t let anyone ever change or stop your drive, or individuality. Keep being interested, and curious.” It was that sort of conversation. It’s that area of reaction that you always worry about, because when they come to that moment of seeing themselves in a magazine – it’s not easy.

With Chloee, was it the same process of finding her?

Yep, same process. Much quicker, in the sense that, like I said before, she was more like – “Cool, that’ll be awesome!” Sort of sensing something ‘rock and roll’ to it all. She was right into everything that it was about: a raw account of a teenager’s life. She was going, “Yep, this’ll be brilliant.” She gave me her dad’s number. I called him, and explained what it’d be, and asked, “How do you feel about that?” He thought about it, and said, “You know what? I would like her story to be told.” Because, he was saying, he wanted people to get an insight into what it is to be a single dad in charge of a teenager, and what it’s like to be a parent.

That’s brave on his part.

Very brave. I mean, it’s very brave of anyone to put their faith in a journalist, it really is. Jeff is an amazing guy; I take my hat off to that man. He’s an amazing father, and I tried to get that in there. Chloee sort of realises it. There were elements in there of the sacrifices he was making as a dad, and I really tried to get that in there, as well. How much of that came across, I don’t know. It might get overshadowed by the other stuff. It’s tough. It was a really tough one, Chloee’s story, in terms of – what do you write in? What do you keep out? And there was a lot of stuff that I kept out. It was a funny process, that one.

You basically walked into a relationship deteriorating; Angela was in the process of leaving Jeff. Was that awkward for you?

Yeah. She was so good about it. But it was an amazing time to start the morning. It was also a great insight into Chloee. Angela just went, “Actually, I’m leaving.” You go, “Can I interview you?” She said ‘yeah’, so you sit there interviewing this woman. It was amazing to capture this relationship in a state of flux, and get an insight into the dynamics between Chloee and Angela, but also the dynamics between her home life and her city life, which were completely different things. It was fascinating. Journalistically, it was an interesting moment to turn up at her house.

You open this one with Chloee’s language; “A boring home on a boring street, in a boring suburb”.

Yeah – “douche”, and all that.

“Douche newsreader reading douche morning news.”

Yeah. That was more just language stuff. I love their language. I hope, though, it didn’t seem too cynical, like I was the cynical journo yet again paying out on a nihilistic teenager. That wasn’t the intention. It was more just going – ‘this is the world you’re about to get into’. It was stepping briefly into her mind, going, “This is Mt Gravatt to me.” And it’s true; Mt Gravatt is so anything but where Chloee’s at in her mind, and I loved that. When we were walking down the street, she lights a fag as we walk out of the house. This street is just total Leave It To Beaver. She’s blowing smoke, and I said something like, “What do you make of this place?”. She just goes, [exhales] “It’s fucked.” And then she’s looking around, and there’s nothing about that street that had any connection for her at all. She wasn’t even acknowledging anything around her. She was totally in her mind, or in her phone.

Were you working on the two pieces in tandem?

They were in tandem, because I had to get them done at the same time. They were always going to be back-to-back, so you have to get the ball rolling on one. That helped in terms of where I took the two pieces, too. You go, “I can set this one here, and go over here to keep [Casey] away from the Queen Street Mall.” But they were written in separate chunks. As it turned out, I had to overlap Casey after I’d written Chloee, because I had to go back to Casey and get more. After Chloee, I knew that there was definitely more than enough, to the point where there was so much that I had to leave out. I knew that it’d definitely sustain a full piece, from start to finish, about her day.

They’re wildly different kids; Casey’s clean-cut, and Chloee’s pretty rough. Did you notice any similarities between the two?

Yeah, definitely. They sort of mirrored each other in the key sense of not knowing where they’re going. They’re not conscious of… ah, no, that’s not fair on Casey. Probably just that key factor of not knowing where they’re going, and trying to find their way, and sort out where they fit in 21st century life in Queensland. That was a common thread. And the sheer influence of friends on them, or how much friends play a massive part in their lives. Their whole worlds revolve around their friends. Everyone remembers that. So those were the two big things – the bonds they had with their friends, which were tighter than brotherhood and sisterhood.

You left a fair bit of space for Angela’s views toward Jeff, in particular, but you didn’t really have a rebuttal from him in there. Did you hesitate before doing that?

Oh, that’s only because she was there at the time. These whole pieces were – “this happens, this happens, this happens”. I could’ve had Jeff, but there was nowhere to put him back in, because I had to talk to each person… I was thinking about having Jeff at the end, because at the end of the day, I called Jeff and said, “Listen mate, she’s still in the city, she’s OK,” and I was going to have that conversation, and there it would’ve been OK. But then it’s never… I don’t know. I just don’t like dropping quotes in somewhere, you know what I mean? Taking it out of context, and bringing in some quote that I’ve gotten down the track. I really enjoy just talking about whatever happens there. And that leaves me out of it, again.

Oh, that’s only because she was there at the time. These whole pieces were – “this happens, this happens, this happens”. I could’ve had Jeff, but there was nowhere to put him back in, because I had to talk to each person… I was thinking about having Jeff at the end, because at the end of the day, I called Jeff and said, “Listen mate, she’s still in the city, she’s OK,” and I was going to have that conversation, and there it would’ve been OK. But then it’s never… I don’t know. I just don’t like dropping quotes in somewhere, you know what I mean? Taking it out of context, and bringing in some quote that I’ve gotten down the track. I really enjoy just talking about whatever happens there. And that leaves me out of it, again.

I could go, “Jeff, what do you think about that? Angela said this about you…” But I’m just telling what I see. I have a moral issue with the whole process of feature writing anyway, so it makes it a bit easier on my conscious if I go, “This is what happened,” and I leave any judgments or anything from me completely out of it. It is what it is. If people take things from it, they can. If they take a bad thing from it, that’s fine. That’s the only real thing about it; it’s genuine reportage, going, “Here’s this moment – this is what I saw.”

The bit where Chloee is getting ready, and says, “I’m going to cake my face to the shithouse” – did you learn a bit about make-up and piercings?

Oh, totally. I don’t know whether she was intentionally trying to. It was so cool, because I knew that that sort of stuff would come into it. I really want to do that, and god bless that girl, because she was like, “Yeah, of course, come in!” to her bathroom, and watch a teenager getting ready. I totally learned terms that I never knew. I’m so out of date; I’m out of touch. Different piercings, make-up, hairstyles, hair dyes, bandannas… a million different things. Such an insight, you know? That was the stuff that I was most fascinated with, and it probably came through in the piece. Constant references to – “this guy’s got this,” and “this guy’s using his headphones as a belt”, and this other guy who had a shirt saying, “drop dead”. I don’t know whether it was a band, or… it was like, “Are you just telling people to drop dead? Brilliant!”

I loved that whole teenage life. It was that whole emo scene life, but it was also fascinating from a fashion sense, too. The most interesting thing to me, for the whole thing, was that it wasn’t about the foul mouths, and some of the perhaps-horrible things that they do to people, but it was all just the lingo, and the atmosphere, and the way that they interact with each other. That’s beautiful stuff, from a feature-writing perspective.

There’s a bit of you in this one. You ask questions, like: “I ask…”

That’s true. I’m always puzzled by this: how do you get to somewhere deep in a story, to bring it somewhere, without bringing yourself in there? So that goes against what I said earlier. I tried very hard not to, but there were some places where it had to be in there, where she was talking about her father, or where I had to ask her about her terms. Like ‘FOBS’ – “fresh off the boat” – which I’ve since learned is a fairly common term. But I guess it’s a way, in that sense, to talk about an intimate discussion. I really wanted it to get to that point where I asked, “What was the saddest moment of your life?” I wanted to get to that point where she said, “When my mum left Brisbane,” because that says something about her and I wanted to bring it up. It was hard to get there without going to some discussion… if you want to get there quickly, that’s all that is, actually. A really quick way is to just go, “I ask.” It sucks a bit, and maybe it’s a bit lame, but I don’t mind if it’s a little bit personal.

Or if you can picture the subject and the journalist in the back of a bus, having a little quiet – well, not so quiet, because her radio was blasting out – but having a little discussion between ourselves. It’s personal. Saying, “I ask” is almost like ‘the reader asks’. I don’t know; that’s probably why.

Tell me about that scene, where Chloee is playing the iPod out loud. Was that extremely awkward for you?

Yeah, it was. It really was. There were some really awkward moments on both of these stories, because people are looking over at me, going “Why…” [interrupts himself] Oh, this came into it constantly in this piece, though; the girl, in particular. Later on, awkward wasn’t the word. I’d be hanging out with these kids who were just letting people have it on the street, yelling out, and I’d be standing there next to them… It was just so funny. People would look at me and think, “Why are you standing there, being party to this sort of behaviour?”

On the bus, I could see this woman in a business suit come in and sit down. Chloee was completely oblivious. They just don’t care. It’s not that they’re trying to be smartarses or attention-seekers; they’re just completely oblivious to the fact that their behaviour is being slightly rude, or would be considered inappropriate. I just couldn’t believe it. She had the iPod, and just didn’t worry about it. Don’t worry about earphones. I don’t know whether she didn’t have any, or… maybe she was doing it for me, so I could jive to the song as well? All these classic emo songs ripping out from the back of the bus, and this woman constantly turning around, but Chloee’s just oblivious because she’s texting or on Facebook.

Me, as a traveller, I’d pick up on that woman looking around in a second. Chloee – nup, no way. That woman was going to have to stop, turn around, and say, “Excuse me.” You can’t give subtle hints to our teenagers these days.

After the bus, you get off in the city and she says, “I’m home.” The first quote from the next section is like, “Fuck you cunt, what kind of friend are you!”, when the guy is talking to his drug dealer on the phone.

Yeah – “Fuck your arse then, cunt!”

You had to include that, obviously, because it’s what he said. Although I note the contrast between Casey’s piece, where there is no swearing, and Chloee’s, which is quite vulgar in that way.

Yeah, it probably was. There was a great lesson in that. That really disgusted people, that teenage girl piece. It was a good lesson for me. You can go so far in the name of… “OK, this is the truth, this what was said,” but – are people ready to read that in print over their Saturday morning cornflakes? In the end, probably not, but I still totally believe, and I’m so grateful we did keep them in there. I know Matt [Condon], my editor, would’ve had to probably fight to keep them. I think there were discussions about how many F-bombs we’d keep in there. Funnily enough, originally I had no ‘dot dot dots’ [censorship] in F-words. I thought, “Nah, let’s just put it all out there!”

That was never gonna fly!

Nah, exactly. [laughs] But the whole point was – hey, this is reality. They have incredibly foul mouths. But not in a way that they’re trying to be foulmouthed or anything; that is just the way it is. When they talk, they throw in a bunch of swear words. And that guy’s disappointment; that’s how he showed his disappointment about not being able to get on: “Fuck your arse then, cunt!” I thought that was very strong, interesting language.

But, in hindsight, when I’m dealing with a teenager next… readers simply don’t like that stuff. Maybe I put too much in there. Maybe it was overkill, and people just went, “Nah, I’m just getting a bit more repulsed by this than I am…” Not inspired, because I didn’t want them to be inspired, but enlightened.

So that’s a terrible thing. That’s not working. That’s a real mistake… I don’t know if it’s a mistake. But then again, some people who read it wrote, “That was the most insightful one you’ve done yet,” so you just go… you’ve got to try and weigh that up. I was just trying to keep true to… like I said before, if I just say what happened, then that’s all I hopefully have to do. But there’s probably places where it’s up to me to leave stuff out, too, for the benefit of the reader not getting repulsed.

You had bits like the ‘fresh off boats’ thing, and “every group needs a token black guy”; the kinds of things that would probably offend the 50 year-old mother reading the magazine.

Totally, yeah. And particularly the way they pay out on adults, the business world; successful people, basically. I found that interesting, but I think people took offence at that, more than anything. I found it interesting from a sense of, “This is how we’re viewed, or you’re viewed, by this particular person.” It gets back to that whole thing. I think people were repulsed and appalled by the piece in a sense…anyone who was appalled by it was disappointed that she was chosen out of all the many teenagers. But that was purely by chance. It was a random selection. But to do honesty to the piece, I had to put in all that stuff. “This is what she said.”

You write about how, “The Scene is a cultural and emotional space and state of mind in the Queen Street Mall.” What was your knowledge or experience of The Scene before you were in there, talking to them?

I’d had an indepth interview with an emo guy once. He was a brilliant, wonderful young man, so I’d known a little bit about it, but I didn’t know how it operated, and I didn’t realise anything about this whole concept of The Scene. I didn’t even know it was called The Scene. I found that fascinating, for one thing; so naïve. But also just how… previously I’d only known them as pretty cool kids. Well, I don’t even know if they’re considered cool, but I knew they were into music, and probably into some bands that I used to like back in the day. I still like The Cure; they’re like my favourite band. But they don’t even like The Cure. I was sort of going, “Disintegration, man, that’s my favourite album!” And they were like – “what?!” [laughs] So it’s a whole different world. And that really made me stay.

I’m telling you, that was the longest fucking day. They just sit in that fucking space…

[from the story] “Two hours sitting in the sun, watching people pass by.”

I’m telling you, man! And that was just when nothing was… I could’ve kept writing generic shit they were saying to people that were passing, paying out on them… But I could not keep doing that. I was just going, “When are they going to do something different?” But they just sit there. They just sit. I’d been with Chloee since 6am, and I remember just going, “This is exhausting. You guys sitting around doing nothing is the most exhausting thing I’ve done in a long time.” I’d be sitting in the middle with them…

Dressed like this, I assume? [gestures to Trent’s clothing; he’s wearing a blue, collared long-sleeve shirt, dark slacks and casual shoes]

Well, I dressed down a little. This is my mid-range dressing down [gestures to clothes], because I had a job this morning where I had go do one of my Saturday [column] things; out at a homeless place, actually. On this day [with The Scene], I wore my Docs… I don’t know. I was going, “Is that what the Goths still wear?” They don’t. But there was some cool comments from them, like, “Oh man, I like your shoes.” I was trying to be ‘cool Trent’. But I wasn’t cool at all. [laughs]

With Casey, I was trying to be ‘cool Trent’, and that’s when the girl said, “[sighs] You are sooo in need of some Vans.” It made me feel so out of touch with that whole thing. It doesn’t take long between timeframes.. but anyway, I’m rambling. So I had dressed down, and it was fun hanging out with them and being a part of it, but it was so weird. That whole lengthy time that they spent there. I did feel like I became part of them after a while; like I was one of the gang. We really came together when the cops stopped us.

What were you doing at that point?

Well, I was standing there in the line. I wasn’t even going to say anything. I thought it’d be interesting, from a journalistic point of view, to see how the cops treat these kids. But I still looked like a dickhead; like some loser who couldn’t find any friends, and had to go and hang out with 16 year olds, and spend his days… This was a weekday, too. This cop is taking the kid’s name, and I’m next. I hand my license to him…

[uncontrollable laughter]

Seriously! It was so funny. But it was only because the guy next to me said, “He’s a journalist!” He was sort of going, “Don’t give us any shit because he’s a journalist, man!” Something like that. So funny. I haven’t been… what do they call that, carded by a cop since I was in grade 12 or something. It was cool. I felt a real camaraderie with the group at that stage. I thought, “Yeah, I’ll just give them my ID…” Because they just come around and do routine name-checks.

In the end, when the kid said something, I told the cop “Yeah I’m doing a story on a day in the life of this girl over here, Chloee.” And he goes, “Just so you know, we do this because…” And that gave another insight into how the parents are terrified for these kids, and the cops have to get their names and details so when the parents call up and say, “Where’s my kid?” They can actually give them some idea. I thought, “yeah, I can understand where the cop’s coming from.” A great moment in my career, though.

You’ve got this great line where you write, “The only time you’re truly free is when you’re 16 and penniless.”

Yeah, and I totally believe that, too. That’s me putting that in there, but I know they totally believe that. And they don’t even realise that. They don’t realise how good their lives are. You’re not free when you’re… like in my situation: I’ve got a wife, two kids, and a mortgage. That’s not very free. All that line was saying was, “This guy was completely penniless, and maybe even directionless, but she’s happier than any millionaire out there.” Everything comes at some sort of cost, but you haven’t made any sacrifices at that age. Nothing costs anything at that age, in terms of your own personal life costs. That’s wonderful freedom, so that you can just run around, and dance inside shops. There’s a wonderful freedom to it, because there’s no cost. Nothing’s going to happen to you. Even if the cops stop you, and lock you up, you probably won’t even get charged. It’s a glorious time. I was trying to get at that. And hence that whole thing I was saying about Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette; this whole world of, “Let them eat cake.” The reckless abandon that comes with being a queen of Queen Street Mall. I like that whole concept.

‘The Logical Song’ makes an appearance; tell me about that. Was that a pure coincidence?

It was totally bizarre. It started because they were going, “What is this song???” This Triple M sort of song, which has probably been played on Triple M every day for the past… And they’re just like, “What is this?” I thought that was cool, but then it was so poignant in a sense of what it was saying. And it’s such a wonderful song, and what that guy was trying to say. You’re going, “Man, that’s great.” Funnily enough, it came back in the Casey story, too. I don’t know why; it must be on the soundtrack they play in those shops, or something. But at the time, it was so good.

It reminded me of “Story Of A Man”, where you had the Talking Heads song ‘Once In A Lifetime’ flowing through the piece, as well.

Oh, yeah! That’s true. Man, I’m a massive music fan, and I love when music comes into any situation and sort of comments. You might be here doing something, but there happens to be some music playing, and if that music has some sort of connection to something else, I’ll always put that in, because I think it’s great. It’s another contextual thing; the sound of what was going on, and all that sort of stuff.

Going into the Commonwealth Bank with Chloee – was that another awkward moment? I’m guessing you might’ve been mistaken for her dad, or something?

Totally! Oh man, seriously. These moments… I’ll never forget this whole story. It was so wonderful. These are just magic moments as a journalist, when you walk in there and you realise how much journalism is all about having humility, and losing your own ego, and getting amongst it; being part of it. Because this Commonwealth Bank lady is looking at me going, “What the fuck are you doing hanging around these girls?” And they just stagger into the bank. I’m telling you, there were rows of accountants, and Chloee – rough as guts – comes in with her friends, and goes, “Can I get a new card, please?” They go – “do you have some ID?” She goes – “nup. Nothing.” It was just fucking classic. I remember thinking, “that is just amazing.” This ‘16 and penniless’ freedom.

But she knew somehow she would get something. Something would happen, you know? But the only reason she was having to go through this was because she had this $10 note, and had such lack of respect for the money that it just fell out of her pocket or something. Just this piece-of-shit $10 note that, somehow, had fallen apart. She tried to feed it into this machine at Coles. It was just hilarious! I couldn’t believe what I was seeing with my eyes. This girl putting this crappy $10 note into this thing, and it was just spitting back out. And then she’s walking up Queen Street Mall, and she just throws it in her pocket, and it hangs out loosely, and I just knew later on…

I should’ve told her, “Chloee, you should tuck that into your pocket a little bit better,” or something. Then she goes, [pats her pockets], “Oh, that $10 fell out”. So then she has to go through this massive, massive rigmarole to get more money. She calls her Dad, and he says no, but it’s like… wow, this is all part of your journey. She wasn’t even phased. When her Dad says, “Piss off!”, she goes, “Lovely,” and chats to someone and gets distracted for another hour. And then – “are we going to get that money?” Oh man, it was just so funny An amazing time.

They had this guy, Justice, as the paternal guardian of the group. You painted that really well.

[laughs] Yeah, that was funny. He was a funny guy. But the funny part about that was their Justice-worship. This guy, I’m telling you… he was just a classic, because every kid on The Scene worshipped the guy. It would be like if Jeff Buckley turned up at a party, and people would be like [whispering behind their hands], “Oh my god, it’s really him!”

It was just unbelievable. He had a black trenchcoat on. He could’ve been a model. He’s a very handsome guy. He’s got this piercing stare. He holds his hand out and is like, [in a deep voice] “Hello, I’m Justice. That’s it; no last name. Just Justice.” And his comments on Chloee were… he’s a wonderful guy, but he has that trait where he feels as though he has some great insights into the world, and his friends. It was wonderful to see the intensity of friendship that he had for Chloee. But it was a funny thing, finally meeting Justice.

I’d heard about him from about 6.30am, and I didn’t get to meet him until about 5pm. It’s like in that movie The Usual Suspects, where they talk about this guy, Keyser Soze. He’s spoken about, but never seen, so you have a whole movie to build up in your mind the majesty of this person that you might one day be fortunate enough to meet… and then he turned up. And he was everything that Chloee said, in terms of his charisma, and everyone was fawning over him. But – that was their world. If anyone else saw Justice, they’d just be like, “Who’s this guy?” But in their world, he was almost like a god. A god-figure. A real leader, guiding them. To be honest, I thought – right now, in Chloee’s life, he’s the best thing to ever happen to her. He really cares about her, and he’s switched on, and thoughtful and wise, and really trying to give of himself and protect her. I really thought his comments about how “she’s a gem”, I thought – that’s great. I really wanted to put that in. People might not understand this girl; someone reading the story is not going to like her much, but she’s very well-liked among this group. She has her own place within this group.

That piece probably should’ve been about The Scene, maybe, in terms of its packaging. It was an interesting one. A fascinating little piece of that series, because she’s probably unlike most teenagers, I’d imagine. I’m sure she shares many similar traits, but still unlike most of them. But yeah – Justice, legend. I’m sure he’s still down there, doing his stuff. There was this great thing with Chloee; she had this other guy, Destry, who was another cool guy. He was the ‘cool happy guy’. I really liked Destry. I was like, “man, he’s a cool kid. If I was that age, I’d be friends with that guy.” I was thinking [from Chloee’s perspective], “This guy’s the guy. You should be asking this guy out, and bringing him home to meet mum and dad. Stick with that guy.” But I think Justice is cool too. Justice was the dark and mysterious, and that always seems to be the one that they go for. But Destry was the wild, open, crazy, interesting, honest and brilliant kid.

You ended it on, “And she won’t be home this afternoon.” Had you tried a few different endings?

Yeah, actually I tried a lot of different endings. The night was about to turn into further debauchery. I was like, “I can’t keep going with this. What’s the point?” And that probably suffered in the piece, too. There was no… I found it incredibly insightful, and enlightening, and alarming, perhaps. But it probably lacked a little bit of insight. That was probably a last-ditch attempt to bring back some insight, just to encapsulate it all. The whole point of Chloee’s story, and the whole point I suggested to the people designing the piece, was: “this is just one girl. She is made up of a million, vastly-moving thoughts. And very quick-moving moments.” That whole piece was like that, and the final paragraph was a shot at trying to show people – “This is who she is. She loves animals, loves her friends, loves Facebook. She’s not good at this. She’s brilliant at this. She’s this, this, this – and she won’t be home this afternoon.” It was sort of tying it back, because right at the start, Angela had said, “Be back this afternoon,” and there was no way that was going to happen. It was riffing back on the end of the Casey piece, which ended sort of ‘up in the air’. It was like – “okay, we’re leaving now. She’s going to go off and do who-knows-what.”

Finally; the criticism of the story that you received. Not a lot of happy readers with this one.

No. I had more bad feedback on that than I’ve ever, ever had on any piece. I can see why. And it’s good. It’s good to ruffle feathers, definitely. I’m so proud that Matt, our editor, went with that piece. It was really courageous of him. The disappointing thing is that some people took the story for what it was intended, and others took it as me saying, “this is what teenagers are today.” If you took it that way, you’d be rightly and justifiably horrified, because not every teenager is by any means like that. I’ve done a million stories on wonderful teenagers, who are… well, I think Chloee is wonderful, inspiring people I’ve met in a long time. I’m sorry that people didn’t see that, or that I didn’t write it in a way that people really saw that. So it was more probably… I think they just found it appalling. Just some horrible insight into one person’s life. But I was really trying to make it insightful and enlightening. But I think it came across as… frightening. And that’s not a good mix.

No. I had more bad feedback on that than I’ve ever, ever had on any piece. I can see why. And it’s good. It’s good to ruffle feathers, definitely. I’m so proud that Matt, our editor, went with that piece. It was really courageous of him. The disappointing thing is that some people took the story for what it was intended, and others took it as me saying, “this is what teenagers are today.” If you took it that way, you’d be rightly and justifiably horrified, because not every teenager is by any means like that. I’ve done a million stories on wonderful teenagers, who are… well, I think Chloee is wonderful, inspiring people I’ve met in a long time. I’m sorry that people didn’t see that, or that I didn’t write it in a way that people really saw that. So it was more probably… I think they just found it appalling. Just some horrible insight into one person’s life. But I was really trying to make it insightful and enlightening. But I think it came across as… frightening. And that’s not a good mix.

Some of it was warranted. Some people had brought their own really weird places to it. I think they had to edit some of wording that people were using in the letters. They were using some really bad words on a girl who’s 16 years old. I think that says much more about the person writing that letter than it does about Chloee, or the piece itself. But others were very measured, and insightful, in their disappointments. But again, it’s all a product of telling it like it was. In the spirit of every one of those things that had come before, it had to be the same. It had to be – “OK, this is what it was.” This is life, and that is the reality.

Which is why it was important to check on how Chloee felt about it. When she said to me, “You’ve captured me,” that was all my intention was, and that made me happy. That helped balance out the very strong-worded letters that I received. And that’s what it’s all about. That’s my job. You’ve just gotta be fuckin’ telling it, and if it’s tough, then I’ve got to be willing to take that, but also to realise that was the point, anyway.

I knew it was going to be a tough read, but my own disappointment was that some people read it in a different way. Some people said, “Thank you so much. That was the most insightful read. I’ve read that story with my teenagers.” That’s great. But you’ve got to take on board anyone who did a problem with it. You learn from where they’re coming from, and keep trying to write the best piece [possible].

Did Chloee like it?

I don’t think she… no-one tends to really enjoy the process, because it’s strange. She had so many people come up to her – all her friends – and say, “you were wonderful. You came across really well.” That just comforted me so much, because if she was copping heat from people… but no-one her age came up to her and said anything but, “man, that is awesome, I can’t believe you’re…”

So that’s great. Good for her. I really just thank her so much for being a part of it, and for being so brave. But it’s tough. You finish them, and you go… [pause] It was there because that was reported. That’s what it was. I was just reporting that world, and that’s definitely worth doing.

++

For more of Trent Dalton, follow him on Twitter: @TrentDalton.

To keep track of Trent’s feature writing, pick up The Courier-Mail each Saturday for the Qweekend magazine, or keep an eye on the Qweekend website, which is updated each Monday with feature stories from the latest issue. You can also follow Qweekend on Twitter.

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

Last year, 24,955 students with disabilities were enrolled in Queensland government schools, roughly 5 per cent of their students. Of that number, 3892 – about 15 per cent – attended 42 state special schools, meaning just over 21,000 were mainstreamed. Within the other schooling sectors, Independent Schools Queensland says 2500 of its students, or about 2 per cent, have ascertained disabilities, while in the Catholic sector, it’s 3 per cent or 4253 students, an increase of 82 per cent since 2007.

Last year, 24,955 students with disabilities were enrolled in Queensland government schools, roughly 5 per cent of their students. Of that number, 3892 – about 15 per cent – attended 42 state special schools, meaning just over 21,000 were mainstreamed. Within the other schooling sectors, Independent Schools Queensland says 2500 of its students, or about 2 per cent, have ascertained disabilities, while in the Catholic sector, it’s 3 per cent or 4253 students, an increase of 82 per cent since 2007.

Definitely. I’m the first person to put myself in the piece; I’m the biggest egomaniac frickin’ idiot journo. I don’t know, I hate it about myself that sometimes I go, “I’m going to put myself in here.” But I only do that when I feel like it’s necessary and that it adds something to the piece. This was totally all about them and it was all about being, as you say, invisible, and just seeing these magic moments, going “I’m not here,” and hopefully getting to the point where they feel like I’m not here.

Definitely. I’m the first person to put myself in the piece; I’m the biggest egomaniac frickin’ idiot journo. I don’t know, I hate it about myself that sometimes I go, “I’m going to put myself in here.” But I only do that when I feel like it’s necessary and that it adds something to the piece. This was totally all about them and it was all about being, as you say, invisible, and just seeing these magic moments, going “I’m not here,” and hopefully getting to the point where they feel like I’m not here. Oh, that’s only because she was there at the time. These whole pieces were – “this happens, this happens, this happens”. I could’ve had Jeff, but there was nowhere to put him back in, because I had to talk to each person… I was thinking about having Jeff at the end, because at the end of the day, I called Jeff and said, “Listen mate, she’s still in the city, she’s OK,” and I was going to have that conversation, and there it would’ve been OK. But then it’s never… I don’t know. I just don’t like dropping quotes in somewhere, you know what I mean? Taking it out of context, and bringing in some quote that I’ve gotten down the track. I really enjoy just talking about whatever happens there. And that leaves me out of it, again.