Announcing my appointment as national music writer at The Australian, from January 2018

I have been appointed as national music writer at The Australian, as announced in the newspaper on Saturday 25 November 2017:

Before I start my next chapter at The Australian in January 2018, I wrote a Medium post to summarise my eight years in freelance journalism. Excerpt below.

Staying motivated during eight years in freelance journalism

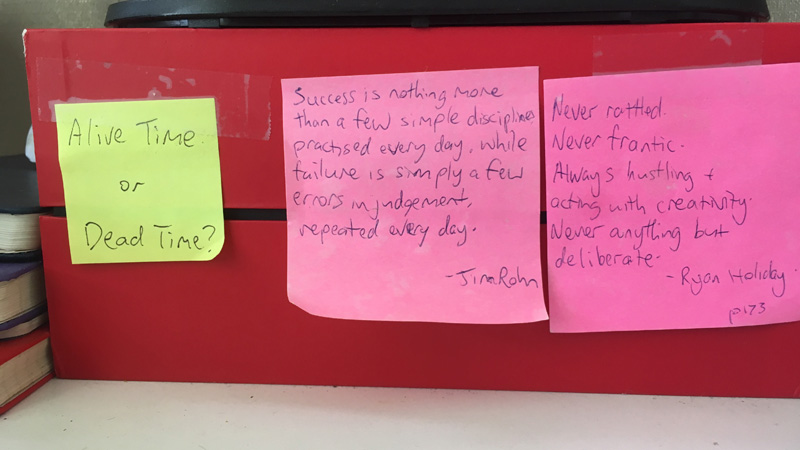

Underneath my computer monitor are three handwritten post-it notes that have been stuck in place for several years. They each contain a few words that mean a lot to me.

From left to right, they read as follows:

1. “Alive time or dead time?”

2. “Success is nothing more than a few simple disciplines practised every day, while failure is simply a few errors in judgement, repeated every day.”

3. “Never rattled. Never frantic. Always hustling and acting with creativity. Never anything but deliberate.”

Since I began working as a freelance journalist in 2009, aged 21, I have worked from eight locations: two bedrooms, two home offices, three living rooms, and one co-working space.

At each of these locations, I took to writing or printing quotes that I found motivational or inspirational. Most of them I have either absorbed by osmosis or outright forgotten, but there’s one I found around 2011 that retains a special resonance. I printed it in a large font, and stuck it to my wall:

“Nothing in this world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not: nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is practically a cliche. Education will not: the world is full of educated fools. Persistence and determination alone are all-powerful.”

That long quote was torn down and tossed during a move, but the message was internalised. If I had to narrow my success down to a single attribute, it’s persistence. I could have quit on plenty of occasions, after any one of a number of setbacks. But I didn’t.

In these motivational quotes, you may be sensing some themes.

I would be lying if I told you that the act of writing and affixing these quotes helped me on a daily, or even a weekly basis. I didn’t repeat them out loud, like affirmations. Most of the time, they were as easy to ignore as wallpaper.

But often enough in recent years, during down moments, or in times of stress or upheaval, I’d shift my gaze from the words–or the bright, blank page–on the computer monitor, and find that these few handwritten notes would help to centre my thoughts.

Let me tell you why.

To read the full story of how I kept myself motivated during eight years in freelance journalism, including significant help from my mentors Nick Crocker and Richard Guilliatt, visit Medium.

And keep an eye on The Australian from January 2018 to see where I take the newspaper’s music coverage in my new role. You can also follow me on Twitter and Instagram.