Qweekend story: ‘Game Plan: Midnight Basketball’, June 2014

A story for the June 14 issue of Qweekend magazine. The full story appears underneath; click the below image to view as a PDF.

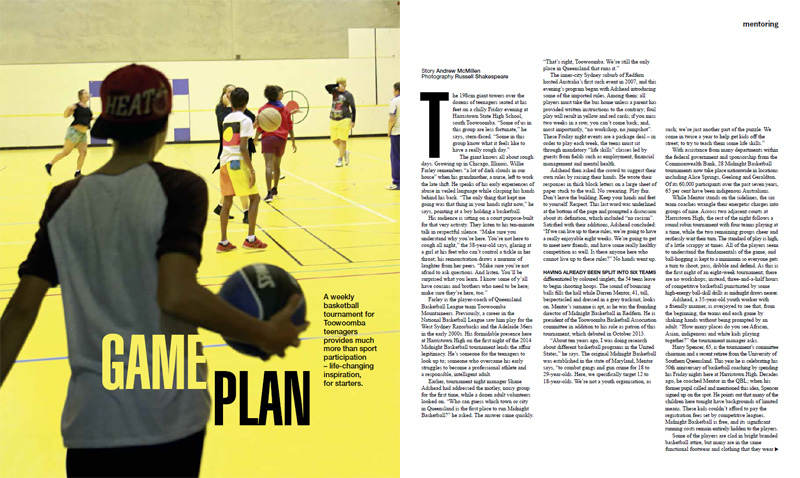

Game Plan

A weekly basketball tournament for Toowoomba teenagers provides much more than sport participation – life-changing inspiration, for starters.

Story: Andrew McMillen / Photography: Russell Shakespeare

++

The 198cm giant towers over the dozens of teenagers seated at his feet on a chilly Friday evening at Harristown State High School, south Toowoomba. “Some of us in this group are less fortunate,” he says, stern-faced. “Some in this group know what it feels like to have a really rough day.”

The giant knows all about rough days. Growing up on in Chicago, Illinois, Willie Farley remembers “a lot of dark clouds in our house” when his grandmother, a nurse, left to work the late shift. He speaks of his early experiences of abuse in veiled language while clasping his hands behind his back. “The only thing that kept me going was that thing in your hands right now,” he says, pointing at a boy holding a basketball.

His audience is sitting on a court purpose-built for that very activity. They listen to his ten-minute talk in respectful silence. “Make sure you understand why you’re here. You’re not here to cough all night,” the 38 year-old says, glaring at a girl at his feet who can’t control a tickle in her throat; his remonstration draws a murmur of laughter from her peers. “Make sure you’re not afraid to ask questions. And listen. You’ll be surprised what you learn. I know some of y’all have cousins and brothers who need to be here; make sure they’re here, too.”

Farley is the player-coach of Queensland Basketball League team Toowoomba Mountaineers. Previously, a career in the National Basketball League saw him play for the West Sydney Razorbacks and the Adelaide 36ers in the early 2000s. His formidable presence here at Harristown High on the first night of the 2014 Midnight Basketball tournament lends the affair legitimacy. He’s someone for the teenagers to look up to; someone who overcame his early struggles to become a professional athlete and a responsible, intelligent adult.

Earlier, tournament night manager Shane Adshead had addressed the motley, noisy group for the first time, while a dozen adult volunteers looked on. “Who can guess which town or city in Queensland is the first place to run Midnight Basketball?” he asked. The answer came quickly. “That’s right, Toowoomba. We’re still the only place in Queensland that runs it.”

The inner-city Sydney suburb of Redfern hosted Australia’s first such event in 2007, and this evening’s program began with Adshead introducing some of the imported rules. Among them: all players must take the bus home unless a parent has provided written instructions to the contrary; foul play will result in yellow and red cards; if you miss two weeks in a row, you can’t come back; and, most importantly: “no workshop, no jumpshot”. These Friday night events are a package deal – in order to play each week, the teens must sit through mandatory “life skills” classes led by guests from fields such as employment, financial management and mental health.

Adshead then asked the crowd to suggest their own rules by raising their hands. He wrote their responses in thick block letters on a large sheet of paper stuck to the wall. No swearing. Play fair. Don’t leave the building. Keep your hands and feet to yourself. Respect. This last word was underlined at the bottom of the page and prompted a discussion about its definition, which included “no racism”. Satisfied with their additions, Adshead concluded: “If we can live up to these rules, we’re going to have a really enjoyable eight weeks. We’re going to get to meet new friends, and have some really healthy competition as well. Is there anyone here who cannot live up to these rules?” No hands went up.

++

Having already been split into six teams differentiated by coloured singlets, the 54 teens leave to begin shooting hoops. The sound of bouncing balls fills the hall while Darren Mentor, 41, tall, bespectacled and dressed in a grey tracksuit, looks on. Mentor’s surname is apt, as he was the founding director of Midnight Basketball in Redfern. He is president of the Toowoomba Basketball Association committee in addition to his role as patron of this tournament, which debuted in October 2013.

“About ten years ago, I was doing research about different basketball programs in the United States,” he says. The original Midnight Basketball was established in the state of Maryland, Mentor says, “to combat gangs and gun crime for 18 to 29-year-olds. Here, we specifically target 12 to 18-year-olds. We’re not a youth organisation, as such; we’re just another part of the puzzle. We come in twice a year to help get kids off the street; to try and teach them some life skills.”

With assistance from many departments within the federal government and sponsorship from the Commonwealth Bank, 28 Midnight Basketball tournaments now take place nationwide in locations including Alice Springs, Geelong and Geraldton. Of its 60,000 participants over the past seven years, 65 per cent have been indigenous Australians.

While Mentor stands on the sidelines, the six team coaches wrangle their energetic charges into groups of nine. Across two adjacent courts at Harristown High, the rest of the night follows a structured round robin tournament with four teams playing at a time, while the two remaining groups cheer and restlessly wait their turn. The standard of play is high, if a little scrappy at times. All of the players seem to understand the fundamentals of the game, and ball-hogging is kept to a minimum so everyone gets a turn to shoot, pass, dribble and defend. As this is the first night of an eight-week tournament, there are no workshops; instead, three-and-a-half hours of competitive basketball punctuated by some high-energy ball-skill drills as midnight draws nearer.

Adshead, a 35 year-old youth worker with a friendly manner, is overjoyed to see that, from the beginning, the teams end each game by shaking hands without being prompted by an adult. “How many places do you see African, Asian, indigenous and white kids playing together?” the tournament manager asks.

Harry Spencer, 65, is the tournament’s committee chair and a recent retiree from the University of Southern Queensland. This year he is celebrating his 50th anniversary of basketball coaching by spending his Friday nights here at Harristown High. Decades ago, he coached Darren Mentor in the QBL; when his former pupil called and mentioned this idea, Spencer signed up on the spot. He points out that many of the children here tonight have backgrounds of limited means. These kids couldn’t afford to pay the registration fees set by competitive leagues. Midnight Basketball is free, and its significant running costs remain entirely hidden to the players.

Some of the players are clad in bright branded basketball attire, but many are in the same functional footwear and clothing that they wear each day. Some come from broken homes, live with single parents, have experienced abuse, or fit into none of the above categories. Some attend private schools and have had comfortable, privileged upbringings. The program does not discriminate: if the kids want to be here and their parents give consent, they’re welcomed with open arms.

At a quarter to midnight, it’s 11 degrees and the kids are sitting comfortably on a bus supplied by local business Stonestreet’s. Some of them have a long journey ahead of them. Since it’s the first night of the year, the bus route will be improvised by a driver studying printed maps of the surrounding suburbs.

Marshalling the teenagers and keeping spirits high is silver-haired, mustachioed tournament security officer Wayne Clarke, 48, a well-known local identity who has his own Facebook page and more than 6000 followers. Clarke will learn tonight that some of these kids live down streets too narrow for the bus, so he’ll walk them a couple of hundred metres to their front door. He’ll wait to sight their thumbs-up from inside before continuing the process until all of his charges are delivered home. It’ll be two in the morning before he’s in bed.

++

The teenagers think they’re here to play basketball. The adults know that what happens on the court is only part of the whole. In the same way that a crafty parent might introduce cauliflower to a fussy eater by masking its taste with mashed potato, these Friday night meetings contain a raft of implicit benefits that begin with the hot, nutritious meal dished up by Rotary Club. Tonight, three weeks after the first games of the 2014 tournament, a barbecue buffet of steak, sausages, rissoles and salad is on offer.

“There’s a couple of good carrots for them here,” Adshead notes. “Years ago, when I started a sports program, an indigenous worker told me, ‘if you can feed them, they will come’. I always put ‘free food’ on the posters, in writing just as big as what sport we were playing.” After this evening’s cohort of 57 – up three from the first week’s attendance – have had their fill, two big boxes of fresh fruit supplied by local grocer Bou-Samra’s are set out between the two courts. By night’s end, they’re empty.

Upstairs, in a classroom with the furniture stacked to one side, Midnight Basketball’s motto of “no workshop, no jumpshot” is in full effect. Phil Renata, a stocky 57 year-old who owns the nearby Team Ngapuhi kickboxing gym, stands while addressing the 20 members of the green and white teams between games. “No one can change who you are; you’ve got to develop who you are, and that’s what we’re here for,” says Renata, gesturing at the four imposing men seated behind him. “It’s all about making yourself better. Maybe you’d like to be like…” Renata pauses. “Who’s a famous sportsman?” A tall girl suggests LeBron James, the 29 year-old Miami Heat basketball. “You might think, ‘I want to be like LeBron James. Nah, I want to be better than him!’ Don’t just be like him; give it 100 per cent. Don’t go in 50 per cent, because you’ll end up hurt.”

Talk turns to respect. Renata asks his four kickboxers, three of whom are brothers, what it means to them. Junior Milo, 17, is the shyest of the bunch. “When I was growing up in New Zealand, I lived across from a gang area,” he says. “I saw a lot of fights and stuff…” He pauses. “So I made sure I respected them.” The adults and children explode with laughter. His brother Justin, 20, was training with NRL club Melbourne Storm a couple of years ago before a back injury ended his league career, and he turned to Muay Thai kickboxing instead. “When you respect people, you learn from them,” he says quietly. “I trained with Billy Slater and Cooper Cronk; I respected them because they’re successful, and that’s what I aspired to be. But by respecting everyone, you can learn off other people, and it kind of makes you a better person at the end of the day.”

Renata acknowledges that the teenagers won’t remember everything said in this room, but they’ll take away the parts that resonate. The four fighters sitting before the teenagers are evidence of how discipline, direction and education can orient lives in a positive direction.

Gerard, the eldest Milo brother at 22, tells the room he’s one year away from completing a Bachelor of Science degree. “What got me there was hard work. Talent can only get you so far. I was really dumb when I was little,” he says, prompting more laughter. “Don’t let anybody tell you that you can’t do it,” he adds. “I wasn’t that smart, but the brain is like a muscle. You can train it. You’re not born smart. Hard work gets you what you want.”

These words might resonate, or they might be forgotten as soon as the teenagers head off to the next game. They might have detected the cauliflower within the mash but decided it didn’t taste so bad after all.

As the night winds down, the weekly best and fairest awards are handed out. In turn, each team’s coach announces a winner; players rise to their feet to accept the awards and shake the adult’s hand, while the crowd applauds their efforts. “Thanks for another great night,” says Adshead. “We’ll see you next week.”

++

The Toowoomba Midnight Basketball grand final is on Friday, June 20. www.midnightbasketball.org.au