The Cottonwool Kid

He’s an inspiration to his beloved Broncos; a motivational speaker; a weightlifter who keeps raising the bar. But it’s a miracle Dean Clifford is even alive.

by Andrew McMillen / Photos by Eddie Safarik

Within metres of the halfway line, a Brisbane Broncos fan cheers from a plastic chair in the first row of Suncorp Stadium’s western grandstand. He isn’t a big man, but he might be stronger than any of the 31,199 people here this Sunday afternoon, including the 26 players on the paddock.

Underneath his Broncos jersey, shoulders and biceps strain against too-tight skin. He shows his appreciation by nodding and clapping his bandaged right hand against his left shoulder, where the flesh is strong.

This is the fan who motivated the Brisbane Broncos to win the 1992 grand final. He has watched more rugby league games in his 33 years than most people will witness in a lifetime but he hasn’t kicked a full-size football since he was a child. He last felt grass under his bare feet at the age of three.

After the final siren, happy that his team has prevailed, he unlatches a gate and heads towards the team dressing rooms, shiny gold walking stick in hand. Nobody stops his slow, steady progress. A black-and-red cap hides a blotchy scalp where hair grows in random patches. His brown eyes, framed by fleshy circles frequently dampened by overactive tear ducts, appear sunken in the absence of eyelids. He can’t blink, so he seems to stare at the Broncos’ captain, Sam Thaiday, who gives him a quick wave and a thumbs-up while leading his team off the field.

Taking up his usual spot against a wall in a warm-up room swarming with fans, reporters and television cameraman, he chats with security staff before he’s welcomed into the home team’s dressing room. A trio of giant younger Broncos stops in the doorway, glancing down to admire his improbably strong frame. One player asks him about his weightlifting training. “I’m aiming for next weekend – another record attempt,” he says. “Make sure you video it, mate,” replies another, impressed. Thaiday stops to greet him with a warm handshake and they share a joke about the game before the fan takes his leave.

Ten minutes later, he arrives at Christ Church on nearby Chippendall Street, where the Sunday evening service is in session. Clad in a maroon polo shirt, Bill Hunter – a thin, handsome former policeman who is the Broncos’ team chaplain – is standing before 40 people of all ages who line the first few rows of pews. “I want to introduce a good friend of mine, Dean Clifford.” Applause echoes from the high ceiling as Dean makes his way down the aisle for an impromptu interview.

“Dean, you were born with a very rare skin disease,” Hunter says. “Basically, your parents were told, ‘Take him home, let him die’, because you weren’t going to live past two.”

“They were told, ‘Hope for the best’,” Dean replies, in a high, slightly nasal voice brought about by his lack of nostrils.

“And how old are you now?” Hunter asks.

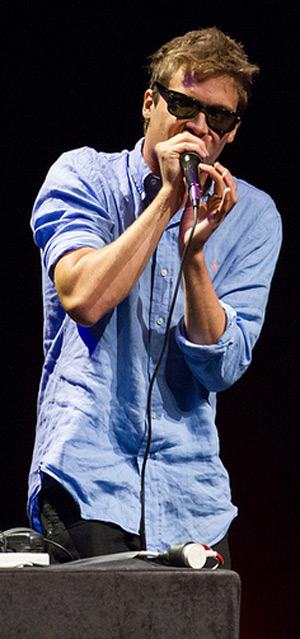

“I’m 33 now,” he says, leaning against his gold walking stick, microphone in hand. “I’m in the best health of my life. I’m planning to be around for a long period to come.”

It’s an unassuming, low-key sort of speech that the audience takes in while nodding and murmuring in admiration. He doesn’t mention the fact that, each morning, the blistered and ulcerated skin that covers his feet, knees, elbows, shoulders and hands requires four hours of scrupulous care and attention; that he has to get up at 4.30am just to make a 9am meeting. To Dean, this morning ritual of bathing and bandaging is an accepted fact of life.

“He’s also a guy who can bench-press 142-and-a-half kilograms,” says Hunter, to a few gasps and exclamations from the audience. “And how heavy are you, Dean?”

“I’ve just turned 70 kilos,” he replies.

“So what percentage of your body weight is that?”

“You’re looking at about 203 per cent of my body weight,” he smiles, waiting a beat for the crowd murmur to die down. “Next week, I’ll be aiming for a new record of 145 kilos.”

++

“He was born perfect,” says Jenny Clifford, 58. “Then, 12 hours later, he started getting a little blister on his bottom.” This blemish spread to the size of an egg yolk; another appeared on the opposite cheek. After three days he was put in isolation; the medical staff were mystified at what was happening to his skin. The doctor who’d delivered Dean visited two days later and gave Jenny some bad news: he suspected epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a condition he’d only seen once before, when training in England. That child had lived for 10 days.

Children with EB are colloquially known as “cotton wool babies” because of the need to wrap their bodies in bandages lest the slightest pressure or contact tear off layers of skin. Dr Dedee Murrell, professor of dermatology at the University of NSW’s Faculty of Medicine, describes EB as “a genetic condition where some of the glue holding your skin together is missing”. There are at least 18 variations of the condition. Dean’s type, junctional EB, is severe and rare – only an estimated 1000 Australians live with the condition today – and life expectancies are short. With junctional EB, most patients die of infection before they’re a year old, says Murrell. How, then, did this boy survive? “He got very good care,” she replies.

Inside the front door of Peter and Jenny Clifford’s home in Albany Creek, northwest of Brisbane, is a sign listing 14 house rules. Among them: Love each other; Be happy every day; Be positive; Be grateful; Never give up. Their first child, Jodie, was unaffected by EB. Only when Dean was born did Peter and Jenny learn that they both carry the gene; their chance of producing a child with EB is one in four.

The pain that dominated Dean’s childhood has lessened, but it is not forgotten. “When I was younger I had no skin at all on my face; it affected my entire face, including my nose and eyes,” he says. “When it all started to heal back, the flesh closed over my nostrils when I was two or so. I don’t remember ever having nostrils or breathing through my nose.”

It was a terrifying time for the whole family. “We wanted to go home and hide, and live our life as best we could with the situation that we had,” says Jenny. “When you’ve got a long-term, chronic illness, you get to a point where it’s about quality of life, not quantity.”

The Cliffords, who spent those early years in the Queensland rural town Kingaroy, made a big deal out of each birthday because they never knew whether it would be his last. They never expected their son to get to school, but were astounded by the support he received when he did. “Who’d like to be Dean’s friend?” asked the preschool teacher; all of his classmates raised their hands.

The Cliffords, who spent those early years in the Queensland rural town Kingaroy, made a big deal out of each birthday because they never knew whether it would be his last. They never expected their son to get to school, but were astounded by the support he received when he did. “Who’d like to be Dean’s friend?” asked the preschool teacher; all of his classmates raised their hands.

A constant refrain on Dean’s school report cards was that he could have done a lot better. It wasn’t merely the time he missed; a kind of fatalism set in. “In high school, in particular, I was struggling for the motivation to put in the effort,” he recalls. His friends in Year Nine would worry about impending deadlines. “I’d say, ‘Don’t worry, I’ve got an operation next month, and if I don’t recover, you’ll get the day off school!’?” His friends would look at him in horror while he laughed at his own dark joke.

Thin, frail and wheelchair-bound, during his adolescence Dean was only ever a slight breeze away from death. His open wounds, blood loss and moisture loss left him malnourished and by 14 he was being fed through a tube. Illness began to distance him from his peers. “I’d go to school and hear about people sneaking out to parties at night, or having sleepovers, and I’d still have to be at home to be connected to the tube feeding into my stomach while I slept because I was so malnourished. Mentally, that side of it irritated me more than the disease, the fact that everybody was going out, starting to have girlfriends, getting their learner’s licences. I was still stuck at home, still incredibly sick, and still basically continuing to hang on to life rather than experience all the things that everyone was talking about … I was on the outside, looking in.”

Yet that awareness of mortality was also strangely liberating. “I finished school at grade 10 because I didn’t expect to be alive for my 18th,” he says. By the age of 15, he jokes, he was already 10 years past his use-by date.

In 1995, he began work experience at a local radio station, 1071 AM, and initially only had the stamina to work one morning per week. The station owner, Marc Peters, says he’s “absolutely glad” he took the chance on employing Dean, who eventually became a popular breakfast radio announcer. “I think it turned his life around,” Peters says. “It gave him confidence; it made him part of the community.”

A change in station ownership in 2000 meant that all staff were made redundant. The Cliffords, high on the confidence-boosting radio gig and the thrill of Dean carrying the Olympic torch through Kingaroy, decided to chance a move to Brisbane in 2001. It didn’t work out; no employer would take on a young bloke who looked like a burns victim, regardless of his skills and experience. The trio returned to Kingaroy at the end of 2001. Dean, dejected, resigned himself to a life of limited means and experiences. “It was a devastating year for me,” he says. “I was just blown away by how obvious it was I’d achieved so much, yet in Brisbane I was still the little kid who everyone was scared to be around.”

“He was quite crushed when I first met him,” says Corinne Young, who became Dean’s disability employment worker after his return. When he was knocked back without reason for a public service job in Kingaroy, Young became determined to find him work. “I didn’t sleep that night,” she says. “I thought to myself, ‘Who in Kingaroy deserves Dean?’?” The next morning she drove to the local Toyota dealership, owned by Ken Mills. It wasn’t a hard sell: aware of Dean’s warm persona on radio, Mills created a part-time marketing role for him that endures today, 11 years later. In 2005, he became a brand ambassador for Toyota Australia and that same year he became an ambassador for his favourite sports team, too.

Marc Peters set those wheels in motion back in 1989, when Dean was nine. “I was told that he’d give anything to be able to go to a Broncos match,” Peters says. “I knew someone who had a connection; he went down to a training session and they virtually adopted him from that day on.” Former Broncos coach Wayne Bennett remembers Dean as “the guy we won the 1992 grand final for”; the then 12-year-old was thought to be close to death. Second-rower Andrew Gee – Dean’s favourite player of all time, still with the Broncos as general manager of football operations – recalls the young boy sitting next to the trophy on the plane home.

It was then-Bronco Brad Thorn who saw the potential for Dean to build his upper body strength and devised an exercise program for him that began with three sets of 10 bench-presses at 30kg. That was in 2006. Thorn has been blown away by the progress Dean has made since then: in the mid 1990s only the strongest Broncos players could bench-press 140kg. “It’s given him so many things,” Thorn says. “You imagine the frustration with his condition as a young man. When he works in the gym he can let out that emotion. He’s got the condition, but there’s still a man in there.”

It was then-Bronco Brad Thorn who saw the potential for Dean to build his upper body strength and devised an exercise program for him that began with three sets of 10 bench-presses at 30kg. That was in 2006. Thorn has been blown away by the progress Dean has made since then: in the mid 1990s only the strongest Broncos players could bench-press 140kg. “It’s given him so many things,” Thorn says. “You imagine the frustration with his condition as a young man. When he works in the gym he can let out that emotion. He’s got the condition, but there’s still a man in there.”

Despite his achievements so far, Dean isn’t satisfied. When we meet he’s following a strict training regimen with his sights set on bench-pressing 145kg. As his parents speak fondly of their only son from their couch, Dean is downstairs in his personal gym where his training partner, Greg Weller, 32, stands behind the bench-press. “When you’re ready, Deano,” Weller says calmly. “Let’s do this, man.”

Two video cameras capture him sitting on the edge of the bench, breathing heavily as he psyches himself up. He lifts 145kg up and out of its resting position. He guides the weight down to his chest and begins to thrust it skyward. “Drive it, drive it, drive it! C’mon man, push it!” urges Weller, but the pressure is too great. After a stifled “Nup!” Weller helps to return the bar to its starting position. Clifford lets out a roar of defeat. Sweat pours from his body. He rips off a glove and tosses it across the room. “So close, hey,” says Weller.

Dean reviews the video footage frame-by-frame until he pinpoints the moment of failure. That word hasn’t existed in his vocabulary for quite some time; it’s been two years since he has failed to meet a weightlifting goal. Talk between Dean and Weller quickly turns to rebuilding his confidence at around the 140kg mark before rescheduling his next record attempt.

From chronically ill cotton-wool baby to seasoned strongman, it’s difficult to imagine a more unlikely weightlifter.

++

“What does raising the bar mean to you?” asks Dean, standing before an audience of staff from a Sydney pharmaceutical company. His left hand grasps his walking stick; his right hand holds a wireless device as he clicks through confronting photos from his childhood. “To me, ‘raising the bar’ would have to be my three favourite words,” he says. “I get chills just thinking about it: how I can take on the next challenge, how I can overcome the next obstacle.”

Since he first stood before a small crowd at the Kingaroy Rotary Club in 2003 and began telling his story, with the encouragement of Ken Mills and Corinne Young, Dean has built a healthy career from motivational speaking. His portfolio is filled with letters of praise from clients as diverse as Harley-Davidson, Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School, Qantas and the Australian Federal Police. Today at Link Healthcare he presents the challenges of his early life in characteristic matter-of-fact style. A couple of women click their tongues simultaneously in surprise at the sight of a close-up photograph showing Dean at his worst: a red, raw, skinless face fills the screen.

Watching him, an earlier conversation comes to mind. His motivational speaking came about after those bruising setbacks in Brisbane in 2001. “I hated the thought of someone else feeling as defeated and as trapped as me,” he says. “No one was prepared to give me a chance. One person said I couldn’t work at the front counter because people would be scared of me; they told me I’d have to work in the back rooms, out of sight. I’ve proved that’s not the case. I’ve stood before 5000 people, speaking; I haven’t hid behind curtains or out of sight. I’m very proud of the fact that I’ve survived.”

“There’s a bit of shock and awe when people first see Dean,” says former Broncos front-rower Shane Webcke, who befriended him in the early 1990s. “I think people automatically think he’s a burns victim.” Dean’s father, Peter, was always troubled by strangers staring at his son in public. “A few years ago we stopped at a McDonald’s in Rockhampton,” he says. “Dean was walking in and this little kid came running out, yelling to his mother, ‘Mum, there’s a scary man!’?”

Dean tends to laugh off these interactions. “It’s normal for me,” he says. “It’s so second-nature that I don’t pick up on it a lot of the time, unless it’s over-the-top aggressive. When we’re out at a pub or a nightclub, my friends and I will turn it into a joke: ‘It takes a lot to look this good – these are designer clothes!’?”

But he does get lonely on occasion. “I don’t have a lot of friends, but those that I do are almost like family to me. They’re very close and important people in my life.” He hasn’t had a girlfriend, though there were a couple of female friendships that came close. “Dating is incredibly hard,” he says, slightly pained. “It’s more about building strong friendships, and if anything develops out of that – great! I do hope that one day, it will.”

Near the end of his talk to the pharmaceutical company, Dean plays the two-minute video of his 142.5kg lift. The staff crane forward as the man in the video breathes heavily, beats his chest four times with his right fist and then lies down on the bench, bandaged hands grasping the steel. Thirty pairs of eyes watch the seconds tick down to the moment when he raises the bar from the rack, guides the weight steadily down to his chest, and then thrusts it skyward. While the staff applaud his effort, Dean can’t help thinking how much more impressive it’d be if he could lift those extra 2.5kg.

++

Postscript: Dean achieved his bench-press goal of 145kg on November 17. He’s already talking about 150kg.

The Cliffords, who spent those early years in the Queensland rural town Kingaroy, made a big deal out of each birthday because they never knew whether it would be his last. They never expected their son to get to school, but were astounded by the support he received when he did. “Who’d like to be Dean’s friend?” asked the preschool teacher; all of his classmates raised their hands.

The Cliffords, who spent those early years in the Queensland rural town Kingaroy, made a big deal out of each birthday because they never knew whether it would be his last. They never expected their son to get to school, but were astounded by the support he received when he did. “Who’d like to be Dean’s friend?” asked the preschool teacher; all of his classmates raised their hands. It was then-Bronco Brad Thorn who saw the potential for Dean to build his upper body strength and devised an exercise program for him that began with three sets of 10 bench-presses at 30kg. That was in 2006. Thorn has been blown away by the progress Dean has made since then: in the mid 1990s only the strongest Broncos players could bench-press 140kg. “It’s given him so many things,” Thorn says. “You imagine the frustration with his condition as a young man. When he works in the gym he can let out that emotion. He’s got the condition, but there’s still a man in there.”

It was then-Bronco Brad Thorn who saw the potential for Dean to build his upper body strength and devised an exercise program for him that began with three sets of 10 bench-presses at 30kg. That was in 2006. Thorn has been blown away by the progress Dean has made since then: in the mid 1990s only the strongest Broncos players could bench-press 140kg. “It’s given him so many things,” Thorn says. “You imagine the frustration with his condition as a young man. When he works in the gym he can let out that emotion. He’s got the condition, but there’s still a man in there.”

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

Last year, 24,955 students with disabilities were enrolled in Queensland government schools, roughly 5 per cent of their students. Of that number, 3892 – about 15 per cent – attended 42 state special schools, meaning just over 21,000 were mainstreamed. Within the other schooling sectors, Independent Schools Queensland says 2500 of its students, or about 2 per cent, have ascertained disabilities, while in the Catholic sector, it’s 3 per cent or 4253 students, an increase of 82 per cent since 2007.

Last year, 24,955 students with disabilities were enrolled in Queensland government schools, roughly 5 per cent of their students. Of that number, 3892 – about 15 per cent – attended 42 state special schools, meaning just over 21,000 were mainstreamed. Within the other schooling sectors, Independent Schools Queensland says 2500 of its students, or about 2 per cent, have ascertained disabilities, while in the Catholic sector, it’s 3 per cent or 4253 students, an increase of 82 per cent since 2007.

“Marijuana Use Most Rampant in Australia,” read a

“Marijuana Use Most Rampant in Australia,” read a