A Conversation With Dave Graney, Australian musician, performer, and author of ‘1001 Australian Nights’, 2011

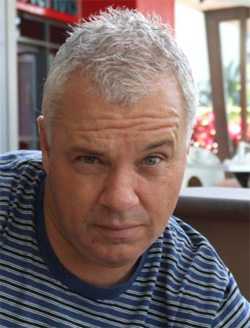

I recently profiled Australian musician, performer and author Dave Graney [pictured right] for The Courier-Mail. His first book, 1001 Australian Nights, was released via Affirm Press in April 2011. You can read my 1,000 word profile of Graney here.

I recently profiled Australian musician, performer and author Dave Graney [pictured right] for The Courier-Mail. His first book, 1001 Australian Nights, was released via Affirm Press in April 2011. You can read my 1,000 word profile of Graney here.

Or if you’d prefer to cast your eyes across the text of our full, 40 minute-long conversation, you may do so by reading the following words. This conversation took place on 11 March, 2011.

++

We’re here to talk about the book. I really enjoyed reading it, Dave.

Thank you.

The thing that probably most intrigued me was how you’ve always positioned yourself as the outcast; the underdog. Is that a fair observation?

I’ve been thinking that. I’ve surprised myself. It’s juvenile. I must change that.

Why is it juvenile?

I don’t know whether it’s juvenile or not, but it’s been my kind of reality, coming from a regional area. Often people in music I find have come from out-of-central things; say, in English music, there’s very few acts from London. Say The Rolling Stones in the 60s, they’re often from outer places; say, Manchester, Liverpool, Leeds, Sheffield. From other places that have informed their perspective, because they’re outside of the biggest city and they’re also in a place that informs their own perspective. David Bowie’s urban; kind of London. I guess that was the reality for me coming from regional South Australia. And I never got over it. [laughs] You can’t fight City Hall.

Not too many artists come from Mount Gambier, do they?

Robert Helpmann… Max Harris, the poet, had something to do with it. Maybe he drove past one day.

So, you’re following in the footsteps of a long line of Mount Gambier artists?

Freaks. [laughs]

At what point did you begin writing this memoir, Dave? Because your observations and memories from your earlier life seem quite well-formed, like you wrote them down almost at the time or soon after.

No, I’ve got a shocking memory, and I always run into people and they think I’m quite rude because they say “You don’t remember me do you?” And I don’t, and I wish I did have a bit of memory, but I’m told in later life that comes back to you in a terrible way; you can’t remember what you did five minutes ago, but memories of childhood are very vivid. I started to write it down in a book when I was in Brisbane, doing a gig at the Old Museum in late 2009, or something.

Some people have that feeling you have to get out of your normal routine of something to provoke good writing. I tried that. The book’s kind of in two parts; you’re talking about this kind of reflection on my earlier life [in the first part], and then the second part, “There’ll be no coming home,” has a more recent focus. It’s kind of “what I thought I was doing, and what I think I’m doing” type of aspect. I started to write it long hand in a book that I got from my parents’ home; a big old 1950s-like ledger. It sounds very prosaic, but it’s like a dramatic kind of book to be scratching in. I started doing it in that, because I spoke to Mick Molloy, the comic, and he said he never writes anything on a computer. He said “everything looks good, and then you go and edit it”. He always writes on a notebook.

Was there a benefit to doing that for you?

I think you kind of think things out a bit more, and then of course you have to type it in eventually, and do the editing like that, but initially you’re thinking probably in a different way in the old-school, the way people have written things for centuries.

Going back to what you said about having a bad memory, does that mean that the first half of the book is made-up?

[laughs] That’s very evil of you Andrew, twisting my words. No, I focused on that trip I took when I finished school and worked in a factory and then drove up eastern Australia, because that sort of thing was a very intense, solitary experience and that’s always been with me. But at other times when I’ve been in the social world, I’ve maybe been a bit less.. they’re the sort of things I’ve found hard to remember. Sort of intense experiences I guess, and in the first band I was in [The Moodists], I guess a lot of that part of the book is how I couldn’t engage with the world, like many people.

Many of the things I’m writing about, I’m conscious and was conscious that they’re not particularly special. They’re common things, and so I tried to write it in a mythological, mythic kind of way, especially my first band. I’m not trying to be, and I hope I’m not being rude to anybody. I’m just… it was an intense, interior experience, and dealing with forces that are kind of uncontrollable, as you are when you’re a teenager, or in your twenties. You can’t articulate things, but you’re doing things in the heat of action. That’s the way I wrote, in that style.

I remember those things and that’s what I was writing about, mythic things in my life that my life has turned around. And also, I’m not really a huge household name, so I don’t think the book I wanted to write is really a linear kind of – “I did this, I did that, I got drunk with this very impressive person. I thought this, I thought that”. I wanted to write it in a different way.

Had you found that approach when you were reading other music biographies, and therefore you wanted to avoid that sort of thing?

Had you found that approach when you were reading other music biographies, and therefore you wanted to avoid that sort of thing?

Well, I love to read books written by musician. Wreckless Eric, a British musician wrote a really great one. His name is Eric Goulden. Zodiac Mindwarp has written a couple of great ones. His book I liked is called Fucked By Rock. He’s a great writer. One by a guy called Mezz Mezzrow, who is a white jazz guy who was a dope dealer for Louis Armstrong. He wrote a really great book called Really The Blues. Charles Mingus’ Beneath The Underdog I really love and Miles Davis of course, with Miles.

I love the autobiographies and I’ve read some books by writers but often they don’t have empathy for the players, and especially nowadays because in every aspect of culture it’s about the audience nowadays, and I’m not happy with that. I think the audience is up itself. The audience needs to lift its game. [laughs] It needs to reinvent itself. Anyway, I’m just being stupid, but I love the writing of Nick Tosches, a New York writer about country music. I love the way he writes, especially about Jerry Lee Lewis. He wrote one about Sonny Liston that I love. There’s a writer – I just read a book about Howlin’ Wolf, which is quite academic, but I fucking loved it because he deserves that really academic, “he did this, he did that with that person” type [writing]. He’s a towering figure.

You mentioned you want to avoid that kind of chronological account of what happened. Were there other stylistic things you wanted to avoid with your book?

No, I wasn’t trying to avoid anything. It has these outlandish kinds of chapter or headings for different pieces, and that’s kind of just my style. A lot of the book is about my style and tone. My music is all about style and content, and the content of style. It’s high-fallutin’ stuff, and it’s loaded, seething with ideas and references. My music’s always been like that, and I just wanted to write in a way, that the flow of my music as well and that came from my life. I’m talking about the flow in a hip-hop style, because I’ve been writing and talking about things in a non-stop way, and all my songs are quite real and alive to me.

It has these kind of headings that are very much in a declamatory way, they’re kind of silly sometimes and other times not, but I love that kind of talk from 19th Century newspapers that William Randolph Hurst taught his writers. They always have those little headings, just the old newspapers. So I wasn’t really thinking in a negative way about “not doing this, not doing that”. I just wanted to have the flow, and I found it quite exciting. My book is like a lot of my music, kind of the way I operate, generally it’s quite positive in a way. I’m not, like Father Ted when he won that best priest award, out to settle the scores with anybody. [laughs] It’s more of like invincible, artistic kind of inner juice. That’s what I wanted.

One of the things that I love about your writing is how self-assured you are. One of my favourite quotes is “I think of how consistently great I have been for such a long time and am warmed by my own regard.” It’s fucking great.

[laughs] That’s just making myself laugh, really.

But even if you are taking the piss…

I was being kind of funny at the beginning of the book, where I said that Australians don’t know how to talk about serious things, and I’ve always enjoyed transgressing and saying the wrong things. I think that’s just a case of me doing that again. Because I know that upsets people.

Yeah, and also because it is so rare to hear artists say they believe in what they’re doing, and that they think they’re good. They’re always downplaying their achievements, and what they sound like, and “oh, this happened by accident”. Yet here you are saying “fuck that, I’ve actually worked at this for a long time, and I believe in what I’m doing”.

[laughs] Well I enjoy creativity and playing music. I’ve worked with Clare Moore. I’m very lucky we’ve had a real tight unit playing music. I love playing with my band. [laughs] Playing music is quite enjoyable.

That’s good to hear. Moving on; what do you think Dave Graney means to people? What do you think people think when they see or hear your name?

I don’t know. I don’t know really. There’s a small number of people that really like my music, and that communicate with me. I’m glad they find my stuff and they get a kick out of different aspects of what I’m doing. Sometimes I see… I was just doing video for a song, we’re putting out an album called Rock and Roll is Where I Hide at the same time too. It’s on Liberation and I was looking at myself singing this song and I do do terrible mugging, acting out and being stupid. My vocal style is full of little cries and gasps, and weird noises and yelps and screams. I guess some people must think it’s kind of fucking weird or something, because most indie rock is so – I don’t know – and I do like some indie rock, but a lot of it’s so uptight that there’s no physicality in a lot of it. We just do it. That’s what’s missing in a lot of… so I’ve got an idea what people think, yeah.

If I was to go on, I’d probably hear pretty negative things [laughs] but not much I can do about that.

Okay, we’ll give that a rest. Getting this book published, was that a hard sell?

I sent the book to a few people. Affirm Press publisher Martin Hughes responded pretty immediately. I’ve liked some of the books he’s put out, like an American writer who lives in Melbourne called Emmett Stinson who did this short story, Ground Zero. And also the comedian Bob Franklin put out a book of almost horror [themed] short stories, which are quite fantastic. It’s a small publisher and very keen in what they’re doing, like a small indie publisher. They’ve been great to work with. I was pretty lucky to find them. I don’t know, I wouldn’t have known who else to approach after them.

What made Martin say yes, do you think?

I don’t know. Maybe he thinks I’m more well-known than I am. I don’t know. [laughs]

Maybe he saw “ARIA Award-winning” and was like “yes, I’ve got to get in on that!”

That could have been it. [laughs] No; a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

Had you always planned to intercut your stories with your song lyrics?

Yeah, I’ve always wanted to do that, to have that flow there. I’ve always wanted to because they both come out of the same thing. I’m glad I had that opportunity.

Those lyrical bits, do they cover the same kind of chronological period?

Yeah, pretty much. I’ve been writing about the same kind of experience [for a long time], and like you were asking, ‘what do people think of me?’; people probably don’t think of me as a songwriter or anything, more than anything else, and in a way that’s been my way I present myself. I’ve always been interested in being a performer, not just being a writer, but you can’t really… I think you’ve got to be one or the other. You have to hold the pose of being a serious songwriter. Like Paul Kelly or Bernard Fanning… [laughs] Those kinds of serious-looking dudes. I’ve never been that sort of person, so I guess to answer your previous question, most people probably think I’m dodgy and that’s something that I prefer, actually. I’d rather be dodgy than worthy. [laughs]

That’s a fucking great quote, Dave! [laughs] I’m intrigued to know why you always call Clare by her full name?

Sometimes when we do things and increasingly people always refer to Clare as my wife. You’ll find, say, Kim Gordon from Sonic Youth is never referred to as “Thurston Moore’s wife”, or Poison Ivy from The Cramps is never referred to as “Lux Interior’s wife”. It’s giving Clare her formal address.

Cool. Does she call you Dave Graney?

[laughs] If she writes a book, she might well do that. [laughs]

I saw your interview with Australian Bookseller where you said “A lot of the book is about where I copped my tone. Tone is everything in music and writing.” I’m interested to know when you had that realisation.

Pretty early on. I loved the tone, but I couldn’t get it. I couldn’t get the remove that a lot of my favourite American artists had, like Jim Morrison, Jerry Lee Lewis, George Jones, Hank Willams, Alan Vega and all of them; they just had this easy tone. I discovered that, like anything, it takes a bit of living to get perspective, to find your own voice and that kind of thing, which is annoying to a teen or twenty-something; your gaze at the world is intense and narrow. You want to say things, but it just comes out in a squeaky kind of way, which makes you even more uptight. But I love that kind of thing.

Rappers, I love. I love different kinds of feel that rappers have, the things they can talk about, and I guess that’s the setting of the music. I love rap music when they just disrespect each other and that, but it never happens in rock music. I wish it did but – it’d probably make rock music go a bit faster if the guy from Jet would come out and call the guy from Wolfmother a dick, in their songs, and they’d have to answer each other. It’d make it go a bit faster. Rock music has pretty much been dead for years, but it’s fuckin’ slow. I mean, they’re still going on about Eric Clapton, and Leonard Fucking Cohen. Christ.

I’m probably not the first to admit surprise at the fact that you are a big hip-hop fan. That really comes across in the book, which I think is cool.

Oh, good. Most really good rock music is informed by hip-hop. When The Black Keys programmed rage, it was all hip-hop.

In that same interview with Australian Bookseller, I saw you say that the upcoming greatest hits re-recorded is your “third debut album”. What did you mean by that; third time lucky?

No, when you do your first record of songs, playing for a long time, you know it inside out, you just go in, they turn on the tapes, and you just yell it onto there. That’s it. There’s no second guessing or worrying, or anything. This record for Liberation is songs that we’ve been playing in our live set because we had the idea for years, the idea that people wanted to hear them, or that come, or ‘we haven’t been to this place for a while – we should play this. People expect us to do this’. Other songs that we just enjoy playing, and songs that we’ve only started playing recently.

So in a way they’re remixes inside a different band, and over time, and so we just talked with Liberation. They do albums for artists’ back catalogue material. We’ve always had a band. I’ve never done many… I do some acoustic guitar gigs, but I don’t enjoy them as much as playing with my band. We said, ‘we’ll record with our band but we’ll just make a rock and roll record’, and we go in and record it all together and it was just like doing a first record. I did one with The Moodists, and one with The Coral Snakes. This is the third one.

I’m looking at the book’s cover [pictured right]. Who did the cover art?

I’m looking at the book’s cover [pictured right]. Who did the cover art?

Tony Mahoney, who’s done all of our record covers going back to 1989.

It’s an interesting style. It looks like it’s cut and pasted it all together.

He doesn’t do it in Photoshop. It’s all hand-done.

I found it interesting in the book, how there are very few mentions of you in solitude writing lyrics or practicing guitar – the activities which are fundamentals for any working musician. Did you leave that out on purpose?

Yeah, it would have been pretty boring. If I talk about writing lyrics or whatever, yeah. I did do it pretty quickly. I’m always just sitting around goofing around on a guitar anyway, so that’s what I do most of the time. Writing lyrics or putting songs together is pretty quick for me and generally I don’t sweat over it too much, not like… who were the worthy types who wrote for days? [laughs]. I’m not like that. I like to have a bit of an immediate flash, it’s what I go for.

It sounds stupid, like if it sounds familiar it must be good, if somebody else has done it. [laughs] I had to do this thing about clothes here in Melbourne. I was involved in this art exhibition of men’s clothes for some reason, and I had to get my picture taken. I said, “I only wear shit that other people have already worn.” [laughs] And they’ve taken the flak for it. I realised in a way my approach to music’s been a bit like that too. I know people can’t hear things that they aren’t already aware of, and they can’t see things that they don’t know they’re looking for, if you know what I mean. So you have to work in forms or words that people are familiar with in a way. That’s my great revelation of recent weeks. [laughs] My approach to music is the way I dress.

There’s a quote in the book where you say you’re talking about the present, you say it’s “a time where the most successful musical acts have no individual definition or focus or personality. People want what they know.” Is that tied to the same kind of thing you’re just talking about?

Yeah, people will try to disappear into generic forms, so they have no individuality. I’m dealing with the same thing like any musician. You have to be recognisably something as well as recognisably yourself. One or the other perhaps, I don’t know, but yeah. Say if I do a gig with an acoustic guitar, acoustic guitar means you’re going to tell the truth. If you wear an electric guitar, it means you’re a liar. [laughs]

Really? Did you just come up with that on the spot?

No, I generally think that. And I do like to play electric guitar [laughs].

That’s great. With the tour diary bits, was it the intention to give a glimpse inside the life of a touring musician?

With the Nick Cave ones?

And the Henry Wagons ones.

A little bit of that, I like the writing I did with Henry Wagons, because I could portray him as kind of my ‘straight man’ in a way, and I really get on well with Henry and I love his music and his ambition. I hope that Wagons really kick it with this album they’re putting out. The Bad Seeds are old friends in a way but in such a different… Nick Cave’s in such a different kind of universe to one I work in. I just thought it was interesting. We were opening for them in Europe and were playing a delicate kind of vibraphone-based, 12 string set to these fucking mad Spaniards. Spanish only like… they’re not very lyrical types, but they just love the flash and the loud noises and everything. Even Nick was breathing a sigh of relief when they got to an English-speaking country. So we have many different relations with people within Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, going back to the beginnings of our kind of work in music. I thought there might be some interesting parts to it, including the deluded bits of my own bullshit.

You’re right, it is interesting. It’s good stuff. I like Nick’s quote on the front cover of the book.

That was very generous of him.

Very generous, yes. “Pure genius,” he said. To which you replied, “thank you, Nick.”

[laughs] Yeah.

So what really surprised me was how the narrative accelerates in the last five pages. Everything up until then had been pretty slow; you talking about your life from an almost emotionally detached perspective, and then it all kind of fell out of you in the most gripping way. It really took me by surprise, and I liked that because I had you pinned down as this too-cool-for-school cat, always making sardonic remarks and dry observations, and then you collapsed that perception in a few hundred words.

Oh, thank you. Well, that was very real. [It was a] full stop to a couple of lines. Yes, it was a very difficult period.

Is that why you were so brief in your description of it, because you didn’t want to dwell on it?

Of my parents and that, do you mean?

Yes.

Yeah, well in a way they’re also intensely private people, too. They’re from that generation [where] if you got your name in the paper it meant you were in trouble with the law. Living in the country, too; country people fucking love their privacy. I would never write anything, would never write anything personal about them [laughs]. I could imagine if they were alive reading something like that, they would hate it.

You’re going to be in the paper with this interview and you’re not going to be in trouble with the law, so that’s positive.

[laughs] Good.

One of my favourite quotes about your early career is that “everything asked should be poor, dirty, and ugly.” Does that still ring true, Dave?

[laughs] Poor, dirty, and ugly – yeah, I’m getting uglier yeah. Poor, yeah. That was someone else [saying] that everything an artist should be – poor, dirty, and ugly.

Ah, that’s right. My apologies.

That’s alright. [laughs]

Do you relate to that concept?

That’s from the song Night Of The Wolverine, a character is talking to someone who thinks that’s what an artist should be, poor, dirty, and ugly. No, I think artists should be sometimes lucky, as well [laughs] You know, rewarded for the hell of it occasionally. I don’t like artists, rock and roll people going on about how miserable they are most of the time, and talking about how stoned they are, and how hungover they are. I find all that stuff pretty boring, and always have.

I mean, I used to be a big drinker. I was a great drinker. I was one of the best! [laughs] But it got a bit boring and I moved to a place where I had to do lots of driving so I just got out of the habit. But there’s some people who write about music are always cheering on rock and roll types. I call them rock and roll dopes really; rock and roll chumps. I’m not really interested. I love the company of musicians, but I don’t like those types that are very unfocused, the kind who need to be standing on the table, shouting, and dancing all the time. I’m not that type. I feel like they’re a bit boring to hang around.

What keeps you going, Dave?

What keeps me going? I’m very interested in… I really like to play music, and it’s quite simple. I’m very involved in different things. I used to be just a stand up singer, and I used to enjoy that gladiatorial type thing and then just standing there with the band behind me and singing and being a wise guy, then I started to play guitar as a performer and increasingly started to enjoy that. The two players we have, me and Clare, we play with Stu Thomas and Stu Perera. I love their company and playing with them. They’re really great musicians. I do enjoy that a lot.

I guess presenting things like records to the world; somebody described it as a leap into the void, that an artist is compelled to take. Eventually artists get tired of doing that. They get exhausted, but I’m still quite excited by doing that kind of thing. I must say putting a book out is quite a different thing because it’s much more of a static thing that people can approach, and that’s different to a recording. I don’t know whether… I think that’s a new thing for me, so this is a bit of a leaping into the void that I’ve never experienced before. It’ll probably be the only kind autobiographical thing I’ll ever be doing! [laughs]

I hope it’s a successful leap into the void, Dave.

Yeah. [laughs]

Based on what I’ve read, I can confirm it is good. Hopefully other people feel that way too.

Oh, thanks Andrew, I appreciate that.

++

For more Dave Graney, follow him on Twitter or visit his website. The music video for his song ‘Knock Yourself Out‘ is embedded below.

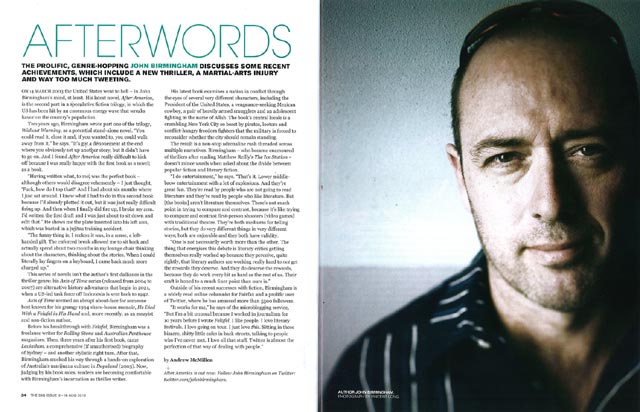

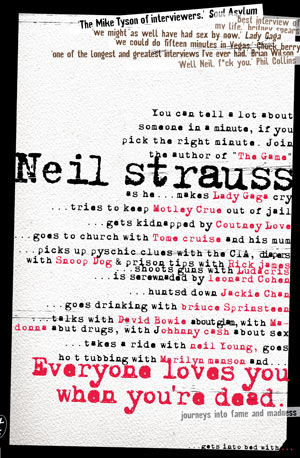

Almost two years ago, I traveled from Brisbane to Sydney to meet Neil Strauss – my favourite writer [pictured right] – for a

Almost two years ago, I traveled from Brisbane to Sydney to meet Neil Strauss – my favourite writer [pictured right] – for a  You state in the intro that “you can tell a lot about a person in a minute, if you pick the right minute”. Was that always the premise of the book?

You state in the intro that “you can tell a lot about a person in a minute, if you pick the right minute”. Was that always the premise of the book? When

When

Yeah, and I loved that. That’s one of my favourite things about this [book] is when you come back and check in with someone later and see how they’ve grown, how they’ve changed, how maybe they take back what they said then, whether they’re sober or whether they’re on drugs. Whether they’re talking rehab speak – it’s a really cool barometer of watching someone grow in these little snapshots. They tell you about your own life too, because you can see how you’ve changed in those interviews as well.

Yeah, and I loved that. That’s one of my favourite things about this [book] is when you come back and check in with someone later and see how they’ve grown, how they’ve changed, how maybe they take back what they said then, whether they’re sober or whether they’re on drugs. Whether they’re talking rehab speak – it’s a really cool barometer of watching someone grow in these little snapshots. They tell you about your own life too, because you can see how you’ve changed in those interviews as well.

I met with Brisbane-based author and journalist Matthew Condon [pictured right] in late June 2010, to discuss his newest book, Brisbane, for a profile in

I met with Brisbane-based author and journalist Matthew Condon [pictured right] in late June 2010, to discuss his newest book, Brisbane, for a profile in  That’s a really good point, because I only realised halfway through the book how important it had been to be doing that journalism for five years, and how in fact I’d touched on many, many things across the city – both contemporary and historical – and I wasn’t as removed from it as I actually thought that I was.

That’s a really good point, because I only realised halfway through the book how important it had been to be doing that journalism for five years, and how in fact I’d touched on many, many things across the city – both contemporary and historical – and I wasn’t as removed from it as I actually thought that I was. Exactly. I think I was in a unique position, having been born here, and left for important years of my life to come back and see this demonstrable change. On one level, yes, enormous change, but as I’ve tried to portray in the book, a constancy running underneath as well. The Brisbane light, the feel, the weather, the lushness, the vegetation – that’s the same as when I was a kid. Other things change around it and I think to get that perspective was unique in the sense that I did have that time lapse, came back to it with fresh eyes, I guess, and it may have been a very different book if it had been written by a writer who had stayed here.

Exactly. I think I was in a unique position, having been born here, and left for important years of my life to come back and see this demonstrable change. On one level, yes, enormous change, but as I’ve tried to portray in the book, a constancy running underneath as well. The Brisbane light, the feel, the weather, the lushness, the vegetation – that’s the same as when I was a kid. Other things change around it and I think to get that perspective was unique in the sense that I did have that time lapse, came back to it with fresh eyes, I guess, and it may have been a very different book if it had been written by a writer who had stayed here.