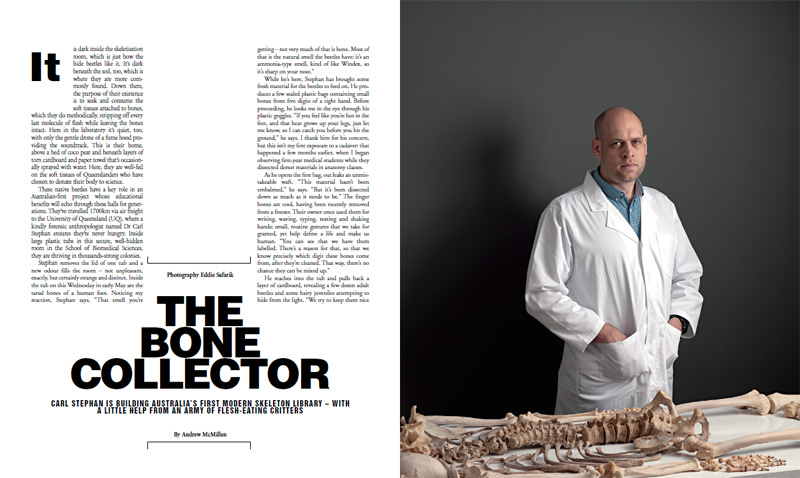

School Of Hard Knocks

Sick children need schooling too. At Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital School, learning proves positively infectious.

++

In a light-filled corner room of a high-rise building overlooking inner-city Brisbane, a visiting local artist leads a class of six rowdy students. Aged between five and seven years old, they are tasked with creating artworks that illustrate their lives. A handful of the best drawings from this schoolwide project will be sent to China, where a school has a reciprocal arrangement. But it’s unlikely the Chinese students will be able to relate to the experience of these children – they are enrolled in a school very few families in Queensland choose to attend. This is the state’s only dedicated hospital school.

Sam Cranstoun presents a cheerful front to the kids’ steady stream of questions and comments. The 28-year-old artist asks the four boys and two girls to use crayons to draw what they like to do. Camping, swimming, board games and PlayStation 4 rank highly, before one boy offers another option with a quizzical look. “School?” he asks, unsure of himself. He is testing the waters: is it cool to admit, at age seven, that you like school? “I’m sure your teacher will love hearing that!” says Sam, flashing a smile to the adults across the room. Gemma Rose-Holt, six, draws a swimming pool at the bottom of an enormous piece of paper, then a sun shining high in the sky. In the last couple of years, she has seen her father’s health rapidly decline for reasons she can’t quite fathom.

Sam continues with the exercise by asking them to consider their place in the world. “Is China bigger than Gladstone?” asks one boy. They talk about their families and school. “Do you guys think about home?” asks the artist. “Yes!” they reply as one, before throwing their talents into happy drawings of the back yards and bedrooms they have left behind.

“There’s an amazing view out the window,” says Sam, pointing behind the students. “Do you guys ever look out there?” At this, the six kids scamper to the windows, pressing their faces against the glass and pointing out the landmarks they can see from the eighth floor of the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital in South Brisbane, which the Prep to Year 2 pupils are visiting for their art class. They can see Mount Coot-tha, the murky river, the Story Bridge in the distance. “I can see the cat-boat!” announces one boy, spying a blue, white and yellow ferry as it powers against the tide. “I can see bull sharks!” suggests another, prompting a laugh from the teaching staff. Not many schools have a helicopter pad on the roof, nor a giant pink bunny rabbit sculpture standing sentry near the entrance. Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital School (LCCHS) has both of these, and when its students are asked to sketch the school, these two features inevitably emerge on the page.

For their final task, Sam turns these young minds toward imagining their future. “What do we want to be?” he asks them, prompting a flurry of ideas. Teacher? Doctor? Journalist? Soldier? McDonald’s worker? Power Ranger? “I don’t know what I’m going to be when I grow up,” says Gemma. She draws a nurse standing beside a bed-bound patient wearing a big smile. That’s her father, Damien. He has no hair because the medicine took it away. “The medicine’s yuck, but he has to have it,” she tells Sam. Little Gemma lives with her mother near the RNA Showgrounds, away from her Sunshine Coast home in accommodation subsidised by the Leukaemia Foundation, while Damien receives treatment.

The students who attend this school are bound by a common experience of illness: either their parents’, their siblings’, or their own. They are from Emerald, Cairns, Chinchilla, Bundaberg and Hervey Bay; from every corner of the state. For some of them, it is their first visit to Brisbane, and the circumstances are less than ideal. Entire families are uprooted from their normal lives and relocated to temporary housing reserved for people in crisis. Their parents have got so much on their plates when they come here that sometimes the last thing on their mind is phoning a school, notifying a teacher about what might become an extended absence from their normal classroom. These tasks fade from view when the spectre of death suddenly appears in sharp focus. Into the breach rush 24 hospital school teaching staff, a compassionate, capable bunch of professionals adept at crafting an individualised education that will define these stricken children.

The school’s impact is wide-ranging, and it sees a diverse population. In 2015, Lady Cilento hospital had 3159 registered students, more than two-thirds of whom normally attended state schools. Of that number, the largest cohort of 21 per cent (663 students) presented with medical conditions; 17 per cent (538) were there for oncology; 13 per cent (410) attended the school because a member of their family was ill, and nine per cent (284) were patients with the Child and Youth Mental Health Service – which is also located on level eight at the hospital – while the remainder found their way there for reasons related to the likes of surgery, diabetes, rehabilitation and heart disease.

More often than not, the hospital teachers’ efforts work wonders for the children and their families. During a midweek excursion to the Gallery of Modern Art at nearby South Bank, Mitchell Cawthray, 12, cautiously approaches a teacher watching over the group of about two dozen students as they eat lunch. He wears a black T-shirt that reads “The Force is Strong In This One”, reflecting an indelible truth of this blue-eyed boy’s tough character. His light brown hair is shaved close to his scalp, and when he turns his head, you can see the scar on the back of his neck where the life-threatening medulloblastoma tumour was removed from the top of his spine almost a year ago. “Are you having a good day so far?” asks the teacher cheerfully. “Great day,” Mitchell replies, nodding. He pauses, weighing his words carefully, then looks around to make sure none of his peers overhear his next words. With a shy smile, he says, “I’ve never really said this before, but I think I like school now!”

++

Most children go through childhood without great complications, and without seeing the insides of healthcare waiting rooms for longer than it takes to receive an immunisation jab, to set an accidental bone fracture in plaster, or to go through the motions of a doctor’s check-up. Mitchell, Gemma and their peers are the unlucky few, and the LCCH treats Queensland’s sickest of the sick. All of the “first-world problems”, as Mitchell’s mum, Janine Cawthray, puts it, fade into irrelevance when your child is diagnosed with brain cancer.

In Mitchell’s case, he and Janine relocated to Brisbane at Easter time last year for his treatment, while his father stayed home in Hervey Bay, managing their small business and caring for Mitchell’s sister as she completed Year 12. “I take my hat off to the teachers,” says Janine. “They not only have to deal with normal academic requirements as per the curriculum; they have to deal with a multitude of personalities – from parents, medical staff – as well as medical requirements and children’s individual needs. They also have to report back to the children’s mainstream school. They’re juggling all of that, and that’s a hard call, but they manage it very, very well.”

In the middle of the building, on level eight, is a place where a familiar timetable reigns between the hours of 9am and 3pm each weekday. It is a place of whiteboards and colouring-in; of assigned readings and class discussions. It is a place of boring adult words such as literacy, numeracy, curriculum, assessment and “personal learning plans”. For some families, the hospital school quickly becomes the only constant in a life now marked by endless blood tests, chemotherapy and invasive surgery, and – sometimes – dramatically shortened horizons.

None of these horrible things happen on level eight, however, where the LCCHS middle and senior classrooms serve an ever-changing cohort of students from Years 5 to 12. Nor do horrible things happen on the ground-floor junior school next door, on Stanley Street inside the old Mater Hospital building, where Prep to Year 4 students are taught. In young lives that have suddenly been dropped into seas of anxiety, pain and uncertainty, these two campuses emerge as towering islands of normality.

There are no school bells here. No uniform, and no rules, per se, only three expectations: be safe, be respectful, and be responsible. Teachers are not known by stuffy honorifics; the students are on a first-name basis with their educators and support staff from the first day. Though visits to these islands of normality are usually short-term matters, these two school campuses can easily act as a home base for months on end, depending on circumstances.

This unique style of teaching has its roots in doctor-soldiers and military nurses returning from World War I in 1918 and concerning themselves with the rehabilitation, retraining and education of limbless soldiers. From that point, it took only a short leap of logic to twig that children ensconced in hospitals required special schooling, too. The Sick Children’s Provisional School opened at the Hospital for Sick Children in the bayside suburb of Shorncliffe on August 11, 1919; it was the nation’s first such educational institution. Since then, it has been relocated several times. A purpose-built school at the Royal Children’s Hospital in Herston opened in 1978; in 2009, it celebrated 90 years of service to more than 60,000 pupils.

Vicki Sykes was the longest-serving principal of Mater Hospital Special School in South Brisbane, which opened in 1983. Appointed in 1986, she served 23 years before retiring in 2009; today, the junior school playground is dedicated in her name with a handsome plaque. In 1986, Sykes described her workplace. “Students come to school from the wards in pyjamas and wheelchairs,” she wrote in an unpublished memoir. “Some are on crutches or have their arms or legs bandaged. During the day some students may need to go off for operations or medical treatment. Teachers don’t know from day to day how many students will be coming to school.”

In that sense, little has changed since the Lady Cilento Children’s Hospital School opened on December 1, 2014. Its purpose is defined by Professor John Pearn in his 2009 history of Queensland’s hospital schools, To Teach The Sick. “Unrealised long-term educational potential has, in the past, been an under-acknowledged legacy of childhood illness,” wrote Pearn in the book’s introduction. “In the context of life’s fulfilment, such may be more serious than any medical after-effects.”

++

The school’s average weekly enrolment is about 150 students, and the student-to-teacher ratio is about seven-to-one. About half of the students are too ill to make it to either of the two campuses at Lady Cilento, so the teachers come to them, providing bedside tuition. They set daily assignments, and return regularly to check their progress. Depending on scheduling, these ward visits might only last 15 minutes if a teacher has a long list of inpatient appointments. But for the bed-bound students, they might also be the only minutes in a day where they are given a task and purpose that’s divorced from their unfortunate medical reality.

When visiting a couple of beautiful sisters from Springfield Lakes who have been diagnosed with cystic fibrosis, a palpable sense of cabin fever permeates their immediate environment. Their world has shrunken to a cruel size. Little girls aged six and eight don’t belong in a small room separated by white curtains, behind a door that must remain closed at all times, and where visitors must wear gloves and gowns before entering to minimise the risk of transmitting infections.

“Homework” is an imperfect word to describe the learning tasks set by these teachers, since the sisters’ entire lives are confined to this room. The hospital, for now, is both their home and classroom. Mid-lesson, a nurse enters to prick their fingers for a blood test. As the precious red liquid is squeezed from a tiny finger, the blonde girl calmly continues reading along to a picture book named Mr Gumpy’s Motor Car with her impromptu teacher, who leaves several worksheets for her to complete. She has long since been conditioned to something that would prompt tears from most other six year-olds.

For these teachers, visiting inpatients on the wards requires a sense of persistence, positivity and optimism. Every day, these teachers see amazing and terrible things, such as degenerative neurological conditions that strip language and meaning from a young boy’s life with each passing week.

From his bedside, it’s a short walk to visit a young girl in a wheelchair whose body hosts a flesh-eating viral infection that has left her face disfigured and her forearms resembling those of a burns victim, wrapped in plastic for her protection. Tourism is her passion, and so the ward teachers resolve to bring her homework that suits this interest.

These teachers are not medical professionals. They cannot fix these problems or treat pain. They can, however, provide stimulation for young minds, if only for 15 minutes each day.

++

After lunch on Thursday, the junior school students file into the flexi-room on level eight for school assembly. Only Prep to Year 4 are in attendance, as the middle and senior grades are still on an all-day excursion to GoMA. Brianna Iszlaub, 11, with patchy tufts of blonde hair, couldn’t attend the latter as her blood count was down today. She stands beside a girl in a wheelchair as the two of them co-host the weekly event, beginning with an Acknowledgment of Country and an energetic, indigenous-flavoured rendition of the national anthem. “Thank you, please be seated,” says Brianna at its conclusion. School staff and a few parents are scattered around the edges of the dozens-strong group, while the students sit in chairs or on cushions.

Once Brianna finishes reading from the prepared script, hospital school principal Michelle Bond says to her, “Good girl.” A short and energetic woman who radiates positivity, Michelle, 49, welcomes the younger students to stand up and present their handmade graphs based on a recent visit to a petting zoo downstairs. The principal – who led Royal Children’s Hospital School since April 24, 2006, and LCCHS since it opened – then presents a handful of awards: to an outstanding student who has shown consideration to his peers; to one who has overcome challenges; to one who has made a positive start after joining the school this week. The group sings happy birthday to a shy blonde girl. “Some of these kids would never be chosen to lead an assembly at their own school; they usually choose the school captains and the sporty kids,” Michelle tells Qweekend quietly. “I’ve had parents come and tell me that their child has never received an award before coming here. It’s lovely that we can do that for them.”

The class’s guest for the day, University of Queensland PhD candidate Maddie Castles, cues a PowerPoint presentation loaded with photos from her recent visit to Namibia. The title slide shows a selfie of her grinning wildly into the camera while a giraffe munches on some leaves behind her. She tells the group about her job studying giraffe social interactions, or “who they’re friends with,” as she puts it. A teacher aide quietly brings a boy in a wheelchair into the room. He is barely conscious, his head held in place by brackets. As time passes, he shuts his eyes and dozes while his classmates leap up for a group photo with Maddie, who might be the first scientist they’ve ever met.

Posted on the door inside Brianna’s Year 7/8 composite classroom is a photo of her before treatment. Her glorious, long locks are framed by a beaming face. The photo was taken when she first arrived at the school from Townsville in January, after being diagnosed with an aggressive lymphoma in late November. Her chemotherapy has stolen her hair and some of her energy. Sometimes she prefers to hide her changing scalp beneath a black beanie with devil horns. But none of this is discussed during school hours.

Brianna’s teacher is Anna Bauer, 35, a bespectacled brunette with sparkling brown eyes who has worked in hospital schools for three years and now can’t imagine teaching anywhere else. “No one here will ask you a medical question,” she says of her classroom. “The kids are so tolerant … You can walk in with a nasal gastric tube and a drip tree, and that’s it. We might give the drip tree a name, like ‘Molly’, and then everybody gets on with what we’re doing. It’s what I wish the real world was like.” Working here sometimes demands that the adults develop coping strategies for their own emotional protection, too. “I have to believe that, when they walk out the door, they live happily ever after,” she says.

In Anna’s current class, Brianna has cancer; the mother of a bubbly Bundaberg girl is being treated for leukaemia; and the fiercely intelligent girl who co-hosted assembly is temporarily in a wheelchair after two recent strokes. But the students she sees aren’t confined to physical illness. “I have so many kids with mental health issues who don’t look sick,” Anna says. “They walk around without baldness, or a nasal gastric tube, or a limp, or a drip tree. There’s no physical evidence, so there’s a real lack of recognition that there’s something wrong with your child. I’m not a parent yet, but oh my God – how awful must that be?”

During Anna’s second week of teaching at the hospital, a student from the previous day didn’t arrive. When she asked a colleague about their sudden absence, she learnt they were being treated in the emergency department after attempting to end their life. “I took that quite badly,” says Anna quietly. That was when her happily-ever-after belief began to cement itself, as a self-protective measure.

Some days are worse than others. “You’re on and lifting, all of the time,” says Anna. “But I find it quite humbling, and incredibly powerful, that it’s my job to make their lives feel normal. It can be sad sometimes, but most of the time, it is not; it is joyous, happy, friendly, loving and supportive. The children are sick, but I’m not a health worker. When I’m in here, and they’re so excited to see me, because I’m not a doctor or a nurse, there’s no time to be sad. You’ve got spelling and times tables to do, and we’re going to have fun while we do it.”

Posted on the door inside Anna’s classroom, beneath the class photos of smiling children at eye level, is a laminated A4 page consisting of a paragraph of white text against a black background, framed by a pink border. I want a life that sizzles and pops, it begins. That first line popped into Anna’s head a little while ago, on a particularly bad day, when her class of six teenage girls were all in a low mood. “And I don’t want to get to the end, or tomorrow even, and realise that my life is a collection of Post-its and unwashed clothes, bad television and reports that no-one’s ever read,” it continues.

The teacher was getting nothing out of them, that day, so she put the spelling lesson aside and assigned the girls a task: to write about what makes them feel better. Anna kicked them off with that first sentence, and encouraged them to fill the page. She did, too. “I want to see what I see through the lens of a camera and drink wine like it’s real grapes and wrap myself in warm towels that smell like my mum’s washing and dance to songs I don’t even like,” she wrote.

The girls pasted the text into an online image editing program, fiddled with the design, printed the results and took them home to stick on their walls. These pages were intended to act as a reminder of all that is good in this world, especially on the blackest days. Anna stuck hers to the wall of a classroom where nobody will ask medical questions, in a building that none of the children particularly want to be in. Her paragraph concludes, “I want to wrap my hands around warm cups of tea with friends that will make me laugh so hard I wee a little bit, and I want every day to belly laugh with my people, glad and grateful, that I love the life I have.”