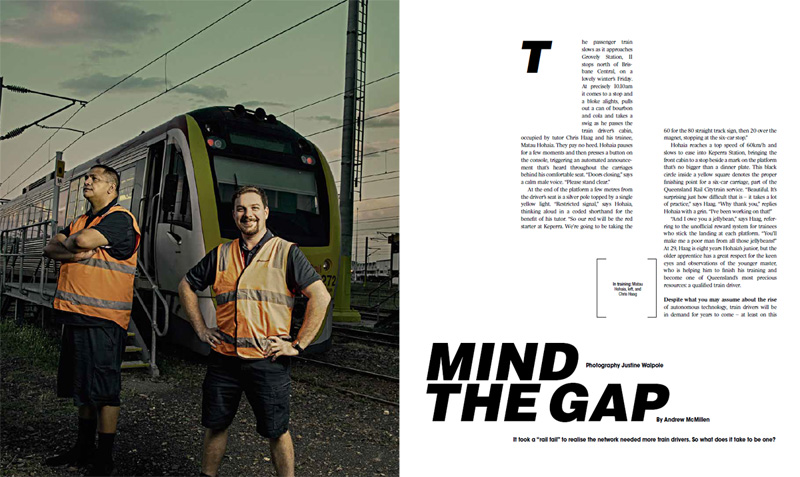

The Weekend Australian Magazine story: ‘Mind The Gap: Training Queensland Rail train drivers’, November 2017

A feature story for The Weekend Australian Magazine, published in the November 11-12 issue. Excerpt below.

It took a “rail fail” to realise the network needed more train drivers. So what does it take to be one?

The passenger train slows as it approaches Grovely Station, 11 stops north of Brisbane Central, on a lovely winter’s Friday. At precisely 10.10am it comes to a stop and a bloke alights, pulls out a can of bourbon and cola and takes a swig as he passes the train driver’s cabin, occupied by tutor Chris Haag and his trainee, Matau Hohaia. They pay no heed. Hohaia pauses for a few moments and then presses a button on the console, triggering an automated announcement that’s heard throughout the carriages behind his comfortable seat. “Doors closing,” says a calm male voice. “Please stand clear.”

At the end of the platform a few metres from the driver’s seat is a silver pole topped by a single yellow light. “Restricted signal,” says Hohaia, thinking aloud in a coded shorthand for the benefit of his tutor. “So our red will be the red starter at Keperra. We’re going to be taking the 60 for the 80 straight track sign, then 20 over the magnet, stopping at the six-car stop.”

Hohaia reaches a top speed of 60km/h and slows to ease into Keperra Station, bringing the front cabin to a stop beside a mark on the platform that’s no bigger than a dinner plate. This black circle inside a yellow square denotes the proper finishing point for a six-car carriage, part of the Queensland Rail Citytrain service. “Beautiful. It’s surprising just how difficult that is — it takes a lot of practice,” says Haag. “Why thank you,” replies Hohaia with a grin. “I’ve been working on that!”

“And I owe you a jelly bean,” says Haag, referring to the unofficial reward system for trainees who stick the landing at each platform. “You’ll make me a poor man from all those jelly beans!” At 29, Haag is eight years Hohaia’s junior, but the older apprentice has a great respect for the keen eyes and observations of the younger master, who is helping him to finish his training and become one of Queensland’s most precious resources: a qualified train driver.

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: Justine Walpole.

Similar anxieties were expressed by Patrick, a 24-year old part-time radio producer who barely sees his partner, Adam, since their schedules rarely align. Yet Patrick admitted “I do get a pang of sadness” when the pair were home at the same time, but both absorbed in their individual computer screens. The author dubs this being ‘together alone’.

Similar anxieties were expressed by Patrick, a 24-year old part-time radio producer who barely sees his partner, Adam, since their schedules rarely align. Yet Patrick admitted “I do get a pang of sadness” when the pair were home at the same time, but both absorbed in their individual computer screens. The author dubs this being ‘together alone’.