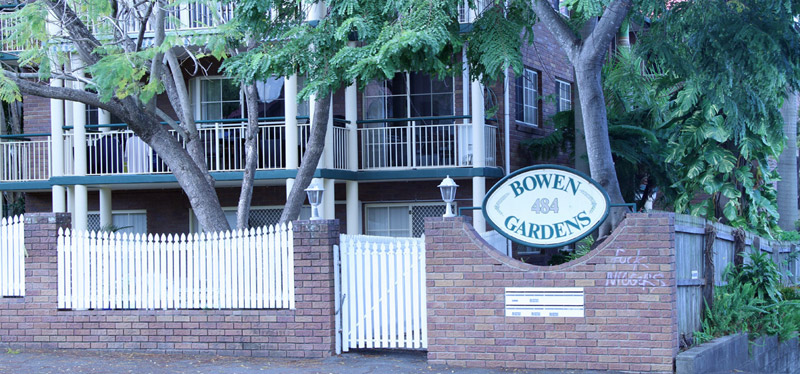

“FUCK NIGGERS,” read the graffiti in large, white, spraypainted letters.

I know the graffiti well because we lived on the same street in New Farm, an inner-city suburb of Brisbane – population 12,500 – which, up until recently, I’d understood as one of the city’s most socially progressive neighbourhoods. Yet there they were, two words utterly incongruous with social progression painted onto the brickwork of the ‘Bowen Gardens’ apartment complex, 484 Bowen Terrace, right beside the eight mailboxes that its residents check daily.

When I first saw the words on 2 August 2012, I stopped and pondered the paint. It was unsettling to see it displayed so prominently, on a highly-trafficked road that runs parallel to Brunswick Street, the suburb’s main thoroughfare. I was compelled enough to take a photo on my phone. This wasn’t right.

As a fan and student of hip-hop, I’m familiar with – and fond of – both words being used in abundance. Expressed in these terms, though – one word followed by the other, in isolation – I encountered a feeling of deep discomfort. Of shame.

After I took the photo, I walked home and told myself that someone else would deal with this problem. I thought about the broken windows theory, which posits that the best way to deal with vandalism and anti-social behaviour is to fix problems when they’re small, lest those small problems become large. Surely, the residents of Bowen Gardens would band together and paint over the graffiti, or at least cover it up. Surely they were embarrassed to see those words every day.

It’s impossible to know whether the words were written with hate in mind, or whether the graffitist was being playful, or ironic. In the absence of context, the imagination of the passerby fills in the blanks. I chose not to see a playful joke. I saw no irony. I saw a statement which jarred with my reality of life in New Farm, Brisbane, circa 2012.

The phrase “FUCK NIGGERS” doesn’t belong anywhere in my life, hip-hop appreciation aside. I don’t want to read those words as I walk down my street. From the moment I first saw the graffiti, I was disgusted. Yet the longer the graffiti lived on, the more it consumed my thoughts; the more it became a part of my life.

Weeks passed. I walked by the words several times each week; to and from the local basketball court, to and from the supermarket. Each time my eyes passed across the text, I asked myself why nothing had been done.

My thoughts turned to buying a can of spraypaint and modifying it myself; perhaps by replacing the second word with “BIGOTS”. I questioned what the ongoing display of these words said about New Farm, about the residents of Bowen Terrace.

I questioned what the words said about me, for I was similarly to blame for this ongoing broadcast. I’d done as much as anyone else: namely, nothing. Since my inaction had formed a kind of tacit acceptance – I’d acknowledged to myself that the graffiti existed, yet I chose not to intervene – I wondered what the graffiti said about my own cowardice.

I thought about the nature of offence, which cut to the heart of why the graffiti unsettled me so: in base terms, it offended me. I found the tag offensive because I read it as a targeted, malicious comment toward a group of humans. I did not sympathise with the sentiment of the comment – “FUCK NIGGERS” – and so I was offended. Again and again.

One afternoon, it all became too much. While practicing basketball at the local court, after walking by the text for perhaps the thirtieth time, I drafted a letter in my head to the residents of Bowen Gardens. It read:

“Greetings! I am a journalist who lives further up Bowen Terrace. I’m writing to enquire about the graffiti that’s been spraypainted onto the front of Bowen Gardens. You may have seen it. You might even have glanced at it today before opening your mailbox to find this note. I would like to ask you a few questions about this graffiti, at your earliest convenience. Please call, message or email me using the details below. ”

I printed and signed eight copies of this note – seven for the residents, one for the body corporate – and pushed them through each letterbox at 3pm on Wednesday, 19 September.

I didn’t expect a reply from any of the residents, as I had effectively drawn attention to their tacit acceptance of the statement. This would undoubtedly cause embarrassment to all who read the note, as it reminded the reader that other locals, too, had eyes and were unimpressed with the graffiti: its content, its permanence, their inaction.

I did, however, expect that the words would be removed by the body corporate, or at least covered up, soon after I’d mailed those eight notes.

I was wrong.

++

On the morning of Wednesday, October 3, an acting detective sergeant with the Queensland Police Service (QPS) knocks on my front door. He’s here because I’d emailed a request to the executive director of QPS media and public affairs the previous morning, stating that I was writing about this particular piece of graffiti. In the email, I wondered if I could show it to a police officer and interview them before the Bowen Gardens brickwork.

My request was passed through a few hands until it landed with the detective sergeant, who works with the Brisbane City Council’s cutely-acronymed Taskforce Against Graffiti. Over the phone that afternoon, he had asked me whether the graffiti was painted on public or private property. I told him that I wasn’t sure; the brickwork is part of a private dwelling, but it extends onto the footpath and is displayed prominently.

The last question he asked me was, “Do you find it offensive?”

“Yes,” I replied.

While the detective sergeant and I walk down Bowen Terrace together – he isn’t authorised to give media interviews, so I won’t identify him – I think about how bizarre it is that this seemingly simple concern has now drawn the attention of a high-ranking police officer.

This is a privilege afforded to me as a journalist, of course: any request from the news media is dealt with seriously, lest an error, inaction or omission land QPS in hot water. We arrive at the graffiti, which has now stood loud and proud before Bowen Gardens for over two months, broadcasting its residents’ apparent bigotry to all and sundry.

If the detective sergeant is shocked by the words, he doesn’t show it. I tell him about the note I wrote to the seven residents and their body corporate two weeks ago, inviting their comment on the graffiti. I tell him that I haven’t heard back from anyone. He writes “FUCK NIGGERS” in his notebook, in quotation marks.

“I don’t like it, either,” he says. He explains that the brickwork is indeed private property; the Brisbane City Council is responsible for the footpath, but not the brick structure itself. He tells me he’ll knock on some doors in an effort to contact the body corporate. The detective sergeant hands me his card, shakes my hand, and we part ways.

All of a sudden, while walking back up the hill, I feel foolish. I had approached this as a concerned New Farm resident first, journalist second, yet by escalating this concern to the Queensland Police Service I’ve leapfrogged the ordinary council graffiti-removal process available to New Farm residents: namely, to fill out an online complaint form and wait for a response. Perhaps I’m making a mountain out of a molehill.

The detective sergeant calls me soon after, saying that he’d spoken to a female resident of Bowen Gardens. She said that the residents had asked body corporate for some chemicals to remove the graffiti. Their attempts to do so had evidently failed. He tells me that he’ll put a removal request through to the council, and that it’ll be gone within 24 hours. We thank each other, and say our goodbyes once again. And that, it seemed, was the end of that.

++

Not quite. Sadly, it took another fifteen days for the tag to be removed. I followed up with the detective sergeant via email on October 10, one week after we’d met and inspected the graffiti together. “From memory, you told me last Wednesday, 3 October, that the incident had been reported and that the graffiti would be removed within 24 hours,” I wrote. “Is this correct, or did I mishear? As of 12pm today, the graffiti is still there.”

I got a reply on October 15, five days later. “I was informed that the Graffiti is usually removed within 24 hrs of reporting if the material is deemed to be offensive which of course it was!” he wrote. “I will take up with the Brisbane City Council and see where they are with this job that was logged that very day that I spoke to you!”

I offered for the detective sergeant to put me directly in touch with the council graffiti removal team. He wrote back: “I will get a response Andrew and let you know as I was of the opinion that it should have been done!”

Three days later, just after midday on Thursday, October 18, another email from the detective sergeant arrived. “Good afternoon Andrew, I have been informed that the Brisbane City Council removed that graffiti this morning and the wall is now clean. Thankyou for bringing it to the attention of Police and the Council.”

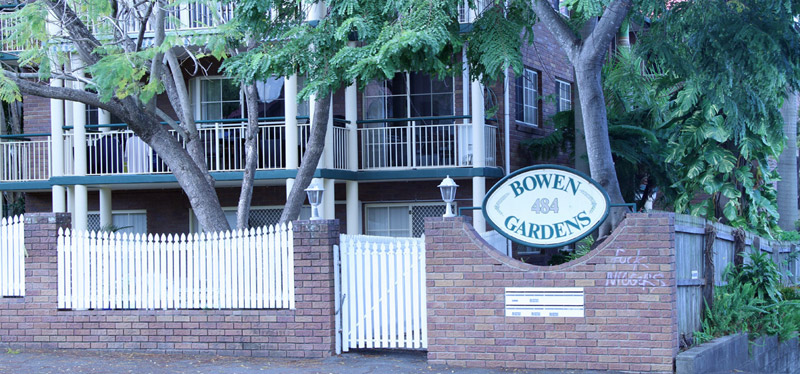

I walked down the street to fact-check. He was right.

I’m glad that the graffiti is gone, but my eyes will be drawn back to that spot on the brickwork as long as I live on Bowen Terrace. Every time I pass by Bowen Gardens, I’ll think about those two words and their 80-odd days of existence. I’ll wonder how long they would’ve stayed there if I hadn’t intervened. (Or if I hadn’t followed up with the detective after our meeting, even.)

I’ll look at the bricks and I’ll wonder why I didn’t act earlier. I’ll wonder why no-one else made a complaint. And I’ll vow to never again let my inaction bleed into tacit acceptance of a malicious, hateful statement made public, writ large, in my own neighbourhood.

Andrew McMillen (@NiteShok) is a Brisbane-based freelance journalist.