Click the below image to read the story in PDF form (link will open in a new window), or scroll down to read the article text underneath.

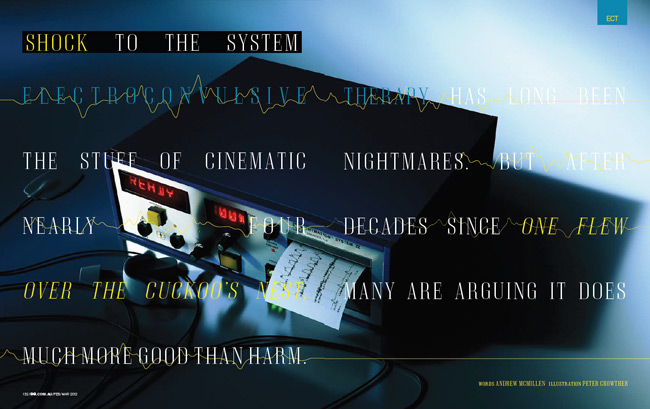

Shock To The System

Electroconvulsive therapy has long been the stuff of cinematic nightmares. But after nearly four decades since One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, many are arguing it does much more good than harm.

Words: Andrew McMillen

As the young man is led into the operating theatre, the smell of salt water and sterilisation fluid hangs in the air. The room is unremarkable; all greys, blues and whites, just like any other theatre in hospitals across the country, except for a couple of innocuous-looking machines stacked on a bench. Twenty-five-year-old John Vincent doesn’t know it yet, but those machines would soon change his life.

Helped onto a gurney, Vincent lies flat on his back as a clamp is placed on his index finger to monitor his oxygen levels. He feels the cold wipe of saline solution on his collarbone, biceps and forehead, before a nurse applies several electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes to trace his brainwave activities. Moments later, a general anaesthetic makes its way up his arm, and he drifts out of consciousness.

Having been sedated, he doesn’t remember what happened next, but it goes like this. A specialist affixes an electrode to the middle of his forehead, and another one above his left temple, then switches on the Thymatrons – those machines in the corner – sending a series of short electric shocks coursing through his brain, bringing on a grand mal seizure. Fifteen seconds later, it’s all over. The current is switched off, the electrodes removed, and Vincent is wheeled into an adjacent recovery room.

It might sound like a scene from a ’70s movie, from the days of roguishly experimental medical procedures, but this was Boxing Day 2010, and Vincent had just received his first course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at Toowong Private Hospital in Brisbane. A psychiatric treatment most commonly used on those with severe depression, ECT – better known by its outdated term, electroshock – is also called upon to treat patients suffering from acute mania or, in Vincent’s case, bipolar disorder. And despite the popular public perception of ECT as a barbaric, archaic practice, the treatment is administered on a daily basis at both public and private hospitals all over Australia.

Growing up, Vincent was a happy kid. He had lots of friends, enjoyed playing soccer, and loved going fishing with his younger brother while on regular camping holidays with the family. Then, aged 17, in his final year of high school, Vincent was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

As he got older, his mental illness became harder to manage. “John was existing, but he wasn’t happy,” recalls his mother, Tina, a kind woman in her early fifties with a fair complexion and green eyes who runs a small business alongside her husband. “He wasn’t right, and at some stage he decided to go off his medication. Unfortunately, with his type of bipolar – type one – when he goes off medication, he goes into a state of catatonia. Everything shuts down; no communication, nothing happens.”

Things worsened as the years passed, and by late 2010, Vincent was living a life of isolation in Townsville, north Queensland. He’d withdrawn from the people around him: friends, family, even the younger brother he lived with. “You know those wildlife documentaries on TV, where they record the animals’ every move, behaviours and moods, and all that?” he asks, his hazel eyes burning with intensity. “I felt like I was an animal; like I was being surveyed.”

This was a dark time for Vincent, who says he spent a lot of time in his room “trying to hide away”. He constantly felt as though there was someone outside looking through the windows at him, recording his behaviour.

One Friday in December, his parents went to Mackay for their first trip away together in a year. The next morning, Tina and her husband received a call from their youngest son. “He didn’t think John was all that well,” she says. “We jumped on the first plane and came home. We spent all Saturday with John. He continued to decline into a catatonic state; not eating, not talking. It was almost like he was in a coma.”

By 5pm, Vincent’s movements had become “robot-like”, with his body barely responding to the signals sent by his brain, and the famil rushed him to the emergency ward at Townsville General Hospital, before he was transferred to the mental health hospital. “It’s pretty sad, because there just aren’t enough facilities,” says Tina, remembering how they how desperate they were for a solution to their son’s illness. “We turned to friends in the medical profession, who gave us a great deal of support and help.”

A man named Dr Josh Geffen was mentioned, who specialised in ECT at Toowong Private Hospital. Vincent had never heard of ECT before his parents brought it up, but since he was in such a low mental state at the time, he didn’t argue. “I just went with it,” he shrugs. “I cooperated, and followed my parents’ advice. I did what I was told.”

He hardly remembers a thing about the journey. His mother continues: “We got John down to Brisbane straightaway, and when Dr Geffen saw the state John was in, the first thing he recommended was ECT,” she says. “We were pretty horrified; we’d heard stories from the olden days of ‘shock treatment’ and that sort of stuff. We hadn’t really given ECT a lot of thought. It’s a little bit frightening, because you really don’t know what’s involved. But Dr Geffen explained everything to us, showed us a DVD, and put our minds at ease. We consented to John having the ECT, and he agreed to it, too.”

They got to work immediately. Doctors warned Vincent that the muscles in his arms, legs and shoulders might feel sore once he came to, after receiving the electric shocks. And indeed, he did feel uncomfortable for a couple of hours – he likens the muscle soreness to the day after a big gym workout – but says, “Afterwards, I felt fine. It took a while for the anaesthetic to wear off, but after that I was OK.”

Vincent’s story is more common than you might think. Statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show that in the 2009-2010 financial year, 26,848 individual ECT sessions were administered throughout Australia – although the exact number of people treated is unclear, as patients tend to have multiple sessions. “A typical course of ECT involves between six and 12 treatments,” explains Dr Aaron Groves, the director of mental health in Queensland, adding that, while ECT can be used on people of all ages, since depression is more common in adults than in children, around 80 per cent of treatments are on patients aged 30 to 80.

Based on those figures, on any given day here in Australia, 73 people get hooked up to a machine and jolted with electricity in the name of medicine. What’s more, far from being a curiosity from the past that hasn’t quite died out, it’s actually on the rise. Why? Well, because it works.

++

Electroconvulsive therapy has its roots in early schizophrenia research. In 1934, Hungarian neuropsychiatrist Ladislas Meduna saw improvements in schizophrenic patients after seizures were induced with chemicals such as camphor and Metrazol. Three years later, Italian neuropsychiatrists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini discovered that these seizures could be more easily induced by electricity. In a TED.com presentation uploaded in October 2007, an American surgeon and author named Dr Sherwin Nuland relayed an eyewitness account of the first time ECT was performed on a human in 1937.

“They thought, ‘Well, we’ll try 55 volts, two-tenths of a second. That’s not going to do anything terrible to him.’ So they did that… This fellow – remember, he wasn’t even put to sleep – after this major grand mal convulsion, sat right up, looked at these three fellows and said, ‘What the fuck are you assholes trying to do?’ Well, they were happy as could be, because he hadn’t said a rational word in the weeks of observation. They plugged him in again, and this time they used 110 volts for half a second, and to their amazement, after it was over, he began speaking like he was perfectly well.”

“It eventually became apparent that it was a much better treatment for depression than schizophrenia,” says Dr Jacinta Powell, clinical director of mental health at the Prince Charles Hospital in Brisbane. “This is how these things develop: psychiatrists make leaps of logic, they try them out, and see whether it works.”

What they hope for with any treatment is remission. So, how does ECT stack up against other methods of treating depression?

According to statistics presented in May 2011 at the American Psychiatric Association Conference in Hawaii, 34 per cent of ECT patients were in remission after two weeks of treatment. Four weeks later, that had risen to 65 per cent; and after a full course of ECT, that figure reached a 75 per cent remission rate. Those success rates aren’t just good; they’re remarkable.

So, why are we still so scared? Perhaps Dr Geffen [pictured right] – the man who treated John Vincent – would have some answers. A stocky, silver-haired man in a dark suit, he leads me into the theatre where John was first treated on Boxing Day. He drags in a couple of chairs from the waiting room, which is adorned with intricate paintings of wildflowers and a poster entitled ‘Understanding Depression’. We sit in the middle of the theatre and begin talking ECT. “Intuitively, it does seem like a worrying thing to do,” he admits, “to pass a dose of electricity through somebody’s brain in order to treat them.”

So, why are we still so scared? Perhaps Dr Geffen [pictured right] – the man who treated John Vincent – would have some answers. A stocky, silver-haired man in a dark suit, he leads me into the theatre where John was first treated on Boxing Day. He drags in a couple of chairs from the waiting room, which is adorned with intricate paintings of wildflowers and a poster entitled ‘Understanding Depression’. We sit in the middle of the theatre and begin talking ECT. “Intuitively, it does seem like a worrying thing to do,” he admits, “to pass a dose of electricity through somebody’s brain in order to treat them.”

And he’s right. A seizure-inducing electrical current sent through the brain, where all our memories, emotions, likes, dislikes, fears and secrets are stored; where our very personality is kept? The mind recoils in horror at the thought alone.

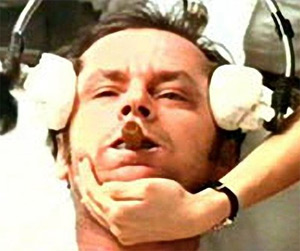

That’s partly because, for the majority of us, who haven’t had any first-hand experience of ECT, our knowledge is mostly based on what we’ve seen in movies. Take One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – the 1975 Miloš Forman adaption of Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel.

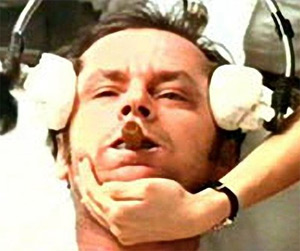

You’ll remember the scene when the main character, Patrick McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, is judged to be so disruptive to the daily routine of his fellow psychiatric ward patients that doctors see no alternative but to treat him with ECT.

McMurphy is led to a bed, his hairline coated with a conductive gel and a piece of leather placed between his teeth. Electrodes are applied to each temple, and his brain is exposed to a current of electricity. There’s no anaesthetic, nor is the patient forewarned of what’s about to happen. McMurphy appears to be in severe pain, with several men restraining his wildly convulsing body. It’s unclear whether McMurphy’s treatment is an attempt to ‘fix’ him psychologically, or simply to punish him for being a trouble-maker, but it was a very convincing performance that won Nicholson an Oscar, a Golden Globe, and a BAFTA for Best Actor.

“It’s a great movie. I love Jack Nicholson; he’s fantastic,” says Dr Geffen, with a grin. “It’s also nothing like modern ECT. It was set during a time when anaesthesia was already involved, so a bit of creative licence has cost us quite a lot of bad press.” He continues with his list of ways the film misrepresents modern ECT. “No treatment electrodes are placed on people until they’re asleep, because it’s not a very pleasant feeling if you’re coming in for your first treatment,” he says. “It’s much kinder for the person who’s anxious about what’s going on.”

It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of treatments do not induce enormous, full-body convulsions like the reaction portrayed by Nicholson. In most cases, the only physical sign of the electrical current is a slight twitching of the patients’ fingers and toes.

It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of treatments do not induce enormous, full-body convulsions like the reaction portrayed by Nicholson. In most cases, the only physical sign of the electrical current is a slight twitching of the patients’ fingers and toes.

At the Prince Charles Hospital, Dr Powell shows me a segment from the 1990s-era television program Good Medicine, in which a greying man in his mid-forties is treated with ECT. The footage of his treatment is so incredibly mundane and unremarkable that I can’t help wondering what all the fuss and controversy is about. Particularly given the guidelines adopted by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists in 1982, which note that it’s “among the least risky of medical procedures carried out under general anaesthesia, and substantially less risky than childbirth.”

“It’s a very effective treatment for very ill people,” agrees Geffen. “It’s more likely to get you into remission than any other treatment.” Success rates with medication when used as a first-line therapy are only 30 per cent, he says. After a year of trying different strategies, this may rise to around 60 per cent in a best-case scenario.

And what about therapy for depression – you know, the kind where you lay on a couch and talk things through?

“The type of depression we see here, people are too sick to be having much talking therapy. Not that talking’s unimportant, but that’s part of the post-recovery.”

Yet somehow, even though lying on the therapist’s couch isn’t the right thing, and months of antidepressants aren’t very effective, people are instinctively more keen to stick to those methods than to volunteer to be subjected to a series of electric shocks.

“A few things soften that,” says Geffen, ever the salesman. “The dose of electricity is quite small; 0.8 to 1 amp. I was treating an electrician, and I asked him, ‘How can I explain it to people?’ He said, ‘Well, it’s about 10 per cent of what a toaster puts out.’ Now I always tell people, ‘Don’t stick forks in toasters, please!'”

Geffen breaks into a wide smile and continues, “Another way to put it is that the current is enough to light up a 25 watt bulb for about one second. Once or twice in the process, I’ll pass the electricity across my hand, and feel a little jolt. But it doesn’t throw me to the ground.”

And of course, ECT isn’t the only instance of doctors using electricity to reset an organ that’s not operating properly; cardioversion, for example, applies the same theory to correct a malunctioning heart. “I do wonder, sometimes, why the person who cardioversed Tony Blair is the ‘cardiologist hero’,” Geffen says, “but I can be painted as a ghoul for trying to treat people’s depression.”

++

Part of our reluctance to embrace ECT, though, may well be because, despite years of research, it’s still a bit of a mystery. We know it works best when used to treat severe depression, but when it comes down to it, we don’t really know why. “At one level, that’s true,” agrees Geffen. “We don’t fully understand all of the mechanisms of its action. However, that’s true of many treatments in medicine. We do know how damaging severe depression is to people’s brains and their lives. At another level, we’re understanding a lot more about how it works, as well as the key chemicals involved in depression: serotonin, adrenaline, dopamine, and this – being a powerful treatment – influences all of them. Most antidepressants work on one, or – at most – two of those. ECT is a potent stimulus for brain cell growth.”

His sentiments are echoed by Dr Daniel Varghese, a Brisbane-based psychiatrist in both the private and public health fields. “I think it’s true to say we don’t really know why or how it works,” Dr Varghese says.

“But then again, we don’t know why or how people get severe mental illness either, because the brain is clearly an inherently complex thing. That’s something that psychiatrists and people with mental illness have to deal with in a range of illnesses: we don’t really know why, but we do know some strategies and treatments that we’ve found to be helpful.”

++

Of course, it’s important to make it clear that ECT is not a catch-all miracle cure for depression, and some of the fears surrounding its usage are real. It certainly has its fair share of detractors.

On a chilly morning in the Brisbane suburb of Highgate Hill, I meet with Brenda McLaren, a spritely woman who loves to talk. Her face is riddled with deep wrinkles, which make her appear far older than her 57 years. Her memory is shot, however, and she has prepared notes in an A5 notebook ahead of my visit. Her relationship with ECT has not been an altogether pleasant one. She was first treated in 1988, as a severely depressed 34-year-old. At first she consented, as she wanted to get better and believed that the doctors at Prince Charles Hospital were acting in her best interests. Over 20 years later, she’s not so sure.

Brenda smokes a cigarette on the sun-soaked front balcony of the Brook Red Community Centre where she works as a peer support worker, and reads her handwritten notes. In 1988, her youngest son was six. “I can’t remember him between the ages of six to 15,” she says. “In some ways, [ECT] must cause some sort of brain injury for that to occur. He talks to me about things, and I honestly don’t remember.”

“My other children would come up to visit me at that time,” she says, “and I wouldn’t know who they were. This would happen quite regularly after ECT. This made them hate the whole system, which is still a big thing with them. It created relationship problems within the family. I’m not saying there weren’t already problems, but it didn’t help. Because… how can a mother forget her children?”

She looks up with sadness in her eyes, and it’s clear the memory loss still hits her hard. “It made me feel very guilty. When you really think about it, in some ways you lose your identity,” she says. “You lose who you are.”

“I would be the most forgetful person here,” she says of her peers at the Centre, which supports people living with mental illness. “I put things down constantly, and never know where they are. I lose things. I believe it’s affected that part of the brain that makes you remember things, long-term. I find it hard to retain information. I find it hard to bring information out. That’s why I’m reading this.” She points at her notebook.

McLaren says she received “dozens” of courses of ECT in her life, the last of which took place around 13 years ago. “I know they do it as humanely as possible,” she says, “but I think it’s barbaric, and in some ways, it’s a form of torture. If I was told I needed ECT today, they would have to take me screaming. Because I will never sign to have ECT again. Ever.”

++

In an adjoining room to the ECT theatre at Toowong Private Hospital, Dr Geffen and his colleagues have written some literary quotes on a whiteboard to keep them focused on the job at hand. “Diseases desperate grown by desperate appliance are relieved, or not at all” – William Shakespeare. “Diseases of the mind impair the bodily powers” – Ovid. “When you treat a disease, first treat the mind” – Chen Jen.

I tell Brenda McLaren’s story to Geffen, interested to hear his thoughts. “I feel sorry for her,” he says, after listening carefully. “I believe her when she says that ECT has damaged her memory, and that this affects her sense of identity. Recurrent ECT of this nature is a difficult scenario; if she was severely suicidal or malnourished from depression it may have saved her life, although obviously at some cost.”

What Brenda described is, he says, a mixture of the common side effect of peri-treatment amnesia – loss of memory of the period around treatment – as well as the rarer retrograde amnesia, which is the loss of memory for “weeks, months, even years” before being treated. “With modern techniques, the peri-treatment amnesia is less severe and retrograde amnesia is even rarer,” he says.

That’s partly thanks to the more recent side-lining of a variation of the treatment, called bitemporal ECT, in which an electrode is placed above each temple (as seen in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). ECT guidelines note that “bitemporal ECT is associated with greater cognitive impairment, but these effects vary from patient to patient. Any memory impairment is usually resolved by 4-6 weeks following ECT, but a number of patients report persistent difficulty with retrograde memory.” The other, now more popular, method is unilateral ECT, where one electrode goes above the temple on the non-dominant side of the brain, while the other sits in the middle of the forehead.

We return to Brenda McLaren’s experiences. “The issue of difficulty learning new information some 13 years later is more problematic,” says Dr Geffen. “It’s not generally described in the literature, and may be contributed to by age, depression, and the impact of lifestyle factors like smoking. But,” he admits, “it is hard to rule out ECT as a factor.”

Geffen has been immersed in this world of ECT for more than 15 years. “We start at 6.30am every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and we’re done by 9am; 10am if we’ve got a long list,” he says. “It’s generally done in the morning; it’s a lot kinder to do it then, as our patients fast from midnight.”

As he said earlier, it’s a treatment for the very ill, and here in this room, Geffen only sees those closest to the brink. I wonder whether the constant exposure to the severely depressed takes a mental toll on him. “When you see patients who are distressed coming in, or patients who have a really good response, you take that home with you and think about it a little bit,” he says, and then smiles. “My wife works in mental health, so it allows for a bit of pillow talk. She’s very familiar with all of this.”

What does he say when asked what he does for a living? “I talk quite openly and freely to my children about what my job is, and explain to them about this,” he says, gesturing at his workspace, with a hint of pride. “Although it’s a stigmatised area, there’s nothing terrible that we do here. We help people who haven’t done anything wrong; they have a brain illness. In that sense, in my social life, I do carry on that view that you can de-stigmatise this.”

++

John Vincent isn’t sure whether he received eight or nine treatments of ECT in total, as he, too, experienced peri-treatment amnesia. “I can’t remember a lot of things that happened when we were back at school,” he says with a shrug. “Birthdays, big events, I can’t remember so much. Things close to me I still remember, though.” Childhood camping and fishing trips, for example, take a while to recall, but his foggy mind does eventually reach back to find the details.

It can be difficult, but he’s philosophical. “I’d rather feel happy, and more myself, than have memories,” he says with a tone of finality. “My health is worth more than having memories.”

Vincent says his course of ECT made him feel more lively. “I’m not so anxious anymore. I’m not short-fused or jumpy. Now I feel more cooperative; I get along a lot more with people.” Not that ECT was a quick fix. “It was a gradual recovery. It wasn’t as though, when I got out, I was right as rain again. It took a while to slowly get to that stage where I felt comfortable.”

His parents stayed at John’s bedside for 12 hours a day through his month-long stay at Toowong Private Hospital. His mother remembers that, within 24 hours of John receiving his first treatment of ECT, she and her husband could see a “definite improvement”.

“John’s had very good results with it. It’s been really quite incredible,” she says. “It’s almost like having a flat battery in a car. You put the jumper leads on and give it a bit of a boost, and it comes back again.”

She doesn’t really understand how it works, and she doesn’t care: she’s just glad to have her eldest son back again. It’s been two months since his last treatment. “He’s on track, and everything is going well. Geffen says, ‘If you go for three months and you don’t need any more ECT, and the drugs are keeping you level, everything’s good,'” Tina says.

“We had no knowledge about ECT until John went into this meltdown and went into hospital,” she continues. “I think the more people talk about it, the better it’ll be. The more I can tell people, and the more open you are about it, the more it will become accepted.”

As for Vincent, now that things are on the up, he’s looking forward to returning to work at his parents’ small business in Townsville. He’d like to settle down with a girl and he can see himself – one day – getting married and having kids, “but they’re a while away yet,” he says with a grin. Vincent isn’t sure what career path he’ll take – something to do with machinery, perhaps, as he’s always had an interest in that area – but he knows that, thanks to ECT, he’s in a better mental state to confront the future than ever before.

*Names have been changed.

Note: due to an error in the production process, a photograph of Dr Josh Geffen’s father, Laurence, appeared in the original article, rather than Josh himself. This error has been corrected in this blog entry.

On a Tuesday morning in March, 80-odd young people wearing red T-shirts hopped off two buses in Lismore, in northern New South Wales, and began canvassing shoppers and retailers in the central business district. Their quest, as declared on their chests, was to help end extreme poverty. Not in Lismore per se, but globally, by petitioning the federal government to bump up its foreign aid spending.

Four years between albums is plenty of time for younger competitors to snatch the crown from Australia’s electronic music kings.

Four years between albums is plenty of time for younger competitors to snatch the crown from Australia’s electronic music kings. This is a messy album in the best way possible. The music created by Brisbane four-piece We All Want To swings back and forth between charming indie pop and rock with jagged edges.

This is a messy album in the best way possible. The music created by Brisbane four-piece We All Want To swings back and forth between charming indie pop and rock with jagged edges. Through change comes artistic progress. On its second album, Perth-based rock act Sugar Army has streamlined the sound out of necessity: the band’s bassist joined fellow Perth group Birds of Tokyo, reducing the quartet to a trio.

Through change comes artistic progress. On its second album, Perth-based rock act Sugar Army has streamlined the sound out of necessity: the band’s bassist joined fellow Perth group Birds of Tokyo, reducing the quartet to a trio.

So, why are we still so scared? Perhaps Dr Geffen [pictured right] – the man who treated John Vincent – would have some answers. A stocky, silver-haired man in a dark suit, he leads me into the theatre where John was first treated on Boxing Day. He drags in a couple of chairs from the waiting room, which is adorned with intricate paintings of wildflowers and a poster entitled ‘Understanding Depression’. We sit in the middle of the theatre and begin talking ECT. “Intuitively, it does seem like a worrying thing to do,” he admits, “to pass a dose of electricity through somebody’s brain in order to treat them.”

So, why are we still so scared? Perhaps Dr Geffen [pictured right] – the man who treated John Vincent – would have some answers. A stocky, silver-haired man in a dark suit, he leads me into the theatre where John was first treated on Boxing Day. He drags in a couple of chairs from the waiting room, which is adorned with intricate paintings of wildflowers and a poster entitled ‘Understanding Depression’. We sit in the middle of the theatre and begin talking ECT. “Intuitively, it does seem like a worrying thing to do,” he admits, “to pass a dose of electricity through somebody’s brain in order to treat them.” It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of treatments do not induce enormous, full-body convulsions like the reaction portrayed by Nicholson. In most cases, the only physical sign of the electrical current is a slight twitching of the patients’ fingers and toes.

It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of treatments do not induce enormous, full-body convulsions like the reaction portrayed by Nicholson. In most cases, the only physical sign of the electrical current is a slight twitching of the patients’ fingers and toes.

Who: Miracle – born Blessed Samuel Joe-Anbah – is a Sydney-based MC and producer who signed a record deal with Sony Music after finishing high school last year. The Ghana-born 18 year-old also has a production deal with Sony publishing imprint Nufirm. His ‘s mixtape releases drew Sony’s ire at first, but now they’re all for it. “They see it as a good way for me to gain fans without their help,” he says.

Who: Miracle – born Blessed Samuel Joe-Anbah – is a Sydney-based MC and producer who signed a record deal with Sony Music after finishing high school last year. The Ghana-born 18 year-old also has a production deal with Sony publishing imprint Nufirm. His ‘s mixtape releases drew Sony’s ire at first, but now they’re all for it. “They see it as a good way for me to gain fans without their help,” he says.

We All Want To – We All Want To

We All Want To – We All Want To