Four album reviews for The Weekend Australian, all published in June 2012.

++

Silversun Pickups – Neck Of The Woods

Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh.

Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh.

The dream pop and shoegaze elements of their sound are most notable in Brian Aubert’s swirling vocals and the waves of distorted guitars that appear in each of these 11 tracks, yet Chris Guanlao’s drumming deserves special mention.

Coming up with original and compelling rock drumbeats is equally as hard as the task that lyricists face in search of themes and melodies, yet both Guanlao and Aubert come up trumps on Neck of the Woods.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Silversun Pickups, though, is that the quality of their output is improving as they age. This album, their third, follows a good 2006 debut in Carnavas and a stronger follow-up in 2009’s Swoon.

This is remarkable when you consider how many rock bands sprint out of the blocks with a remarkable debut and watch their credibility and fan base wane with each subsequent release.

Not these four: they’re versatile enough to do high-BPM, hard-edged tracks such as ‘Mean Spirits’, right after an elegant slow-burner such as ‘Here We Are (Chancer)’, and clever enough to lace both performance styles with drama and a sense of urgency.

It’s quite a talent that they exhibit. Credit songwriting and production, the latter courtesy of U2 and R.E.M. associate Jacknife Lee, in equal parts.

Label: Warner

Rating: 4 stars

++

Joe McKee – Burning Boy

These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011.

These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011.

Snowman were among the darkest, scariest acts to lurk at the fringes of Australian indie rock: though they crisscrossed the nation dozens of times, garnered occasional Triple J airplay and toured as part of the biggest festivals, their gloomy, confronting style ensured many chose to overlook their three (excellent) albums.

Burning Boy, McKee’s solo debut, is a much gentler affair. His deep voice, surprisingly, is front and centre: McKee favoured higher-pitched shrieks and yells on most Snowman tracks. It’s a nice change.

Stylistically, Burning Boy bears similarities to Adalita Srsen’s debut album, Adalita, released last year: Srsen, too, chose to step away from the noise and bluster of her rock band Magic Dirt, and the result was a beautiful collection of songs that featured little more than voice and six-string. Here, McKee opts to linger over syllables in that hypnotising baritone, while finger-picked guitar and atmospheric string arrangements drift in and out of focus.

These are delicate songs of introspection, marked by occasional bursts of energy: bass, drums and an electric guitar interject toward the end of ‘An Open Mine’, while pulsing standout ‘A Double Life’ could well be a Snowman b-side.

McKee’s noted fondness for looped vocal motifs appear in ‘Golden Guilt’; his command of clever wordplay is best exemplified in album opener ‘Lunar Sea’ (“Am I sinking deeper / Down into the lunacy?”). An absorbing and accomplished debut.

Label: Dot Dash/Remote Control

Rating: 4 stars

++

Def Wish Cast – Evolution Machine

What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music.

What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music.

Australian hip-hop has enjoyed a healthy ascent in the past two decades, and a Sydney crew named Def Wish Cast was instrumental in establishing the art form locally with its 1993 debut album, Knights of the Underground Table.

Almost 20 years later it returns with third LP Evolution Machine. A lot has changed within the genre: hip-hop acts now jostle with rock and pop bands for festival headline slots.

The stakes are higher; tastes more discerning. Evolution Machine is a good album, but given the popularity of this sound nowadays it’s much tougher to impress the listener. Def Wish Cast — comprising three MCs in Die C, Sereck and Def Wish, plus DJ Murda One — has enlisted a wide range of producers, but the result is an uneven mix.

Evolution Machine comprises 11 tracks (plus two short interstitials) and almost as many producers, including acclaimed names such as Plutonic Lab, Katalyst and M-Phazes. The Resin Dogs-produced first single ‘Dun Proppa’ is pure fire; so too ‘I Can’t Believe It’, a loving ode to the genre built on the album’s best beat.

The three MCs exhibit strong wordplay and distinctive voices, particularly Def Wish, whose rapid-fire lyricism is a consistent highlight.

There’s a wealth of ideas here, and many of them work, but the lack of cohesion gives the impression that these tracks were assembled in disparate home studios. Though the hip-hop crown has been usurped by younger peers, Evolution Machine is a fine addition to Def Wish Cast’s too-short discography.

Rating: 3 stars

Label: Creative Vibes

++

Rainman – Bigger Pictures

Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam.

Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam.

On his second album, Brisbane MC Rainman – real name Ray Bourne – treads a fine line between making those mistakes and breaking new narrative ground.

‘Big Night’ is a by-the-numbers take on the aforementioned hedonistic tropes; ‘The Valley’ is centred on the Queensland capital’s nightclub district (“A happy home that you might find violence in/ You might find your future wife in the Night Owl line”).

Yet, to his credit, Rainman uses ironic distance and sober observation in the latter track rather than glamorising the suburb and its characters.

It’s a refreshing change and a sign of Bourne’s maturity. His vocal delivery is eerily similar to that of his one-time mentor Urthboy, of Sydney band the Herd. As with that MC, Rainman’s calm, measured tones work well in both chorus and verse.

The beats on Bigger Pictures‘ 15 tracks are uniformly excellent: credits are split between seven producers, including the MC himself.

Bourne is superlative when writing about weightier matters: on penultimate track ‘Too Much’ he snipes at his generation’s indifference to the ills of mass media (“They keep it simple so that we can remember/ A little grab that sounds like an ad/ But don’t get apathetic, motherf . . ker, get mad”); in ‘The Bigger Picture’, his introspective narrative ends an impressive album on a high note.

LABEL: Born Fresh/Obese

RATING: 4 stars

Four albums into a career that blossomed with the release of second LP Granddance in 2006, Sydney quintet Dappled Cities here present their most accomplished collection. Granddance brought the band into the national consciousness via a string of outstanding singles; Lake Air is a complete work, one so good it deserves to take Dappled Cities much further.

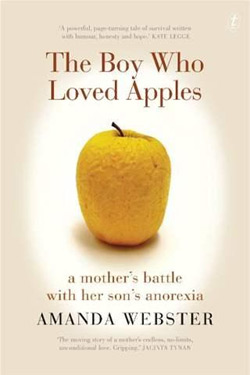

I didn’t know this until I read The Boy Who Loved Apples, in which first-time author Amanda Webster takes on twin challenges: to write a confessional account of the most difficult time of her life and to educate readers about the complexities of an illness few understand intimately, especially as it applies to boys. She succeeds on both counts.

I didn’t know this until I read The Boy Who Loved Apples, in which first-time author Amanda Webster takes on twin challenges: to write a confessional account of the most difficult time of her life and to educate readers about the complexities of an illness few understand intimately, especially as it applies to boys. She succeeds on both counts.

The young man at the heart of this band has been worth watching since he emerged in late 2009. Jonathan Boulet’s self-titled, self-recorded, self-produced debut was bursting at the seams with ideas (he played all the instruments and sang, too.) Boulet’s songwriting didn’t always hit the mark, but he certainly showed promise.

The young man at the heart of this band has been worth watching since he emerged in late 2009. Jonathan Boulet’s self-titled, self-recorded, self-produced debut was bursting at the seams with ideas (he played all the instruments and sang, too.) Boulet’s songwriting didn’t always hit the mark, but he certainly showed promise. In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as  Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh.

Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh. These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011.

These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011. What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music.

What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music. Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam.

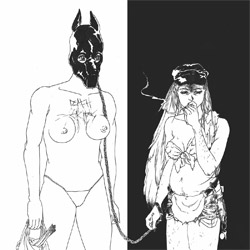

Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam. By combining the ethos and aesthetics of punk-rock and electronica with hip-hop, Californian trio Death Grips have established an entirely unique sound.

By combining the ethos and aesthetics of punk-rock and electronica with hip-hop, Californian trio Death Grips have established an entirely unique sound.