The concept of paying month-by-month to stream music from your computer and smartphone remains a relatively new idea in Australia. In the last year or two, a number of contenders have emerged. Nokia has had their ‘Comes With Music’ service for a while now. Sony launched their ‘Music Unlimited’ product in February 2011. Hulking, canary-yellow retailer JB Hi-Fi launched their own streaming platform in December 2011, dubbed ‘NOW’. BlackBerry, Samsung and Microsoft all have proprietary systems operating in some capacity. Rumours abound of Spotify’s Australian launch. A site named Guvera offers a slight twist on the idea: ‘guilt-free’ mp3 downloads. None of these services have yet gained any real traction in the Australian market.

The concept of paying month-by-month to stream music from your computer and smartphone remains a relatively new idea in Australia. In the last year or two, a number of contenders have emerged. Nokia has had their ‘Comes With Music’ service for a while now. Sony launched their ‘Music Unlimited’ product in February 2011. Hulking, canary-yellow retailer JB Hi-Fi launched their own streaming platform in December 2011, dubbed ‘NOW’. BlackBerry, Samsung and Microsoft all have proprietary systems operating in some capacity. Rumours abound of Spotify’s Australian launch. A site named Guvera offers a slight twist on the idea: ‘guilt-free’ mp3 downloads. None of these services have yet gained any real traction in the Australian market.

Clearly, it’s becoming an increasingly crowded marketplace, as app developers and record companies alike cosy up to the assumption that most people don’t give a fuck about music ownership anymore. That whatever CDs, vinyl and cassettes they own gather dust on a shelf somewhere, immobile and largely useless in the era of interconnectivity. These companies believe that most music fans – ‘consumers’ – simply want the ability to take all the world’s music with them, wherever they go. For a monthly fee, of course.

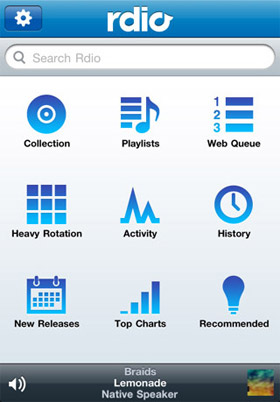

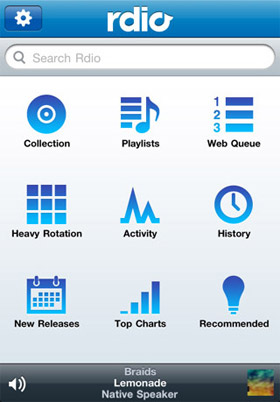

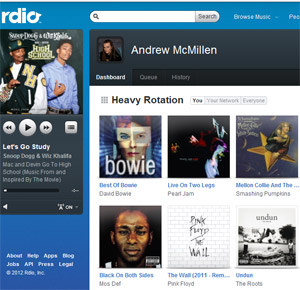

The newest contender on the Australian market is named Rdio [pictured above]. It’s web-based and also has apps for the main phone platforms (iOS, Android, BlackBerry… Windows Phone?). It was founded by a couple of the guys behind Skype, it’s been public in the States since August 2010, and it’s pronounced exactly like it’s written (‘radio’ minus the ‘a’). For AUD$13.90 per month, you get access to unlimited PC and mobile streaming of their library, which apparently consists of over 14 million songs. Ahead of a launch party at Bondi’s Beach Road Hotel in early February 2012, a couple of the Rdio guys flew me to Sydney, bought me lunch, and answered my questions as best they could.

Andrew: How long has Rdio’s Australian launch been in the works?

Scott [Bagby, VP Strategic & International Partnerships; pictured left]: I first came down to Australia to start the discussions at Easter 2011. We were pretty much sewn up by the end of the year. So not quite a year.

Scott [Bagby, VP Strategic & International Partnerships; pictured left]: I first came down to Australia to start the discussions at Easter 2011. We were pretty much sewn up by the end of the year. So not quite a year.

There’s been a few streaming services available in Australia over the last few years, but none of them have had any real success in terms of market penetration. Is that fair to say?

Scott: Streaming services on the whole, globally, are quite nascent. I was just hanging out with a bunch of labels. I can’t verify these numbers, but this label guy told me that worldwide, there’s only about 7 million subscribers, to any streaming service. It is very much in the early days of all streaming services. But the potential is huge. They’re planning on massive growth in the area, especially this year. I think you’ll find that here in Australia, as well. There’s still an education that needs to happen for the user to understand streaming services. [They need to] just learn about ‘em, and use ‘em, and get what I refer to as the ‘a-ha’ moment, of why streaming services are so much better than buying individual tracks.

Carter [Adamson, co-founder; pictured right]: But seven million music subscribers in a world where everyone loves music? There’s a lot of room to grow. For ten years, we’ve had various fits and starts with digital music: DRM, tethered CDs, and that kind of stuff. We have services like Rhapsody in the US, who are stuck at around 600,000 subscribers. Now within the past year, you have more than a handful of services that have well over a million subscribers apiece. That only happened within the past year. You have markets like Australia, where 40% of all music revenue is digital music revenue. Korea’s over 50%. For the first time, digital music revenue globally is growing quicker [than physical sales]. I think we’re now at an inflection point with digital music subscription services.

Carter [Adamson, co-founder; pictured right]: But seven million music subscribers in a world where everyone loves music? There’s a lot of room to grow. For ten years, we’ve had various fits and starts with digital music: DRM, tethered CDs, and that kind of stuff. We have services like Rhapsody in the US, who are stuck at around 600,000 subscribers. Now within the past year, you have more than a handful of services that have well over a million subscribers apiece. That only happened within the past year. You have markets like Australia, where 40% of all music revenue is digital music revenue. Korea’s over 50%. For the first time, digital music revenue globally is growing quicker [than physical sales]. I think we’re now at an inflection point with digital music subscription services.

Scott: The timing’s also great, because of the iPhone and other smartphones. People want to take their music with them. Back in the old days, when I was travelling around I used to have a CD case [for a discman], but that’s just too much of a hassle now. With this streaming service, we have 14 million songs at your disposal, no matter where you are in the world. You can download songs to your phone, switch ‘em out; every Tuesday, there’s new releases [on Rdio]. These sort of things – that’s the education that has to happen, and that’s the ‘a-ha’ moment when you get all of that going. The perfect alignment of the ubiquity of smartphones is what’s really helping it along.

Carter: Well, connected devices. Any single device that can talk to the internet is a playback device now. Whereas before you had one device; a record player, CD player, 8-track player. Now there’s a wide array of devices that are effectively playback devices, so it no longer makes sense to buy one song for each device. It no longer makes sense to port all the downloads that you bought a la carte via external hard drive to every single device that you have. The only thing that makes sense is for you to access it seamlessly wherever you are, using whatever platform or device you have.

Using the US service as an example, what percentage of users are using Rdio on their phones?

Carter: Over 85% of our subscribers are on the higher-priced tier. [Note: PC-only access to Rdio is AUD$8.90 per month – five bucks cheaper than the PC/phone combo.] And that makes sense, because the value proposition has always been seamless mobility. People always wanted to move their music around. No-one’s ever bought a song on iTunes to just play it on their computer. They’ve been waiting for 10 years for this whole seamless mobility thing to become a reality. Now it’s finally here.

Scott: I think that’s one of the reasons that the music industry faced such a piracy problem in the past, because they didn’t offer it in a format in which people wanted to consume music. Now that it’s coming into that format, you see a lot of people moving into services like ours. They wanted to listen in several places at once, but they couldn’t, so the only way they could do it is to steal it. It was still happening up until a month ago in Hong Kong. Everyone was saying, ‘I want to buy music, but there’s no iTunes, there’s no digital services here. I can’t buy what I want; you leave me no choice but to steal it’. These people were lawyers, bankers – people that had the means [to pay], they didn’t want to steal it, they just didn’t have it.

Carter: And also, the price has never been so low. We’re talking about 34 cents a day for access to the world’s music, across all your devices. That’s an insanely low price.

Tell me about that education process you mentioned earlier. How do you turn seven million streaming music subscribers into seven billion?

Scott: [laughs] Well, one of the benefits is to have your music everywhere and anywhere. Part of my job is to go around to all the different countries and get the rights sorted, so at least it’s available to everyone. Once it’s available, the education process is an ongoing one. And it’s one for the entire industry to be involved in. The best way to get there is to allow people to get that ‘a-ha’ moment. That moment comes at certain times, like when they’re at their friend’s place, they’re sitting around and they want to hear that song from their childhood that they’re all laughing about. Obviously no-one has it in their collection anymore, but then you – boom – you stream it down, you get a big laugh, and it kicks off. You can almost have Rdio and some beers, and you have a party.

I think a lot of people would be using YouTube for that purpose at the moment.

Scott: But YouTube, again, isn’t all that mobile. I mean, not as mobile as Rdio is.

Which labels do you have on board for the Australian launch?

Scott: We’ve got all the major labels, and we have some indies like Shock, MGM and Inertia. We won’t open up in any market, anywhere in the world, unless we have the domestic music, as well. At the end of the day, it’s about enjoying the content. That’s what makes a good service – the titles that you have. We have a whole team who just make sure that we have as much music as we can on the service. Funnily enough, I was just in Germany, doing a radio interview with a DJ. She is in love with Australian music, specifically Australian hip-hop. She used to fly out here, buy the CDs, then play it on her station. What she loves about this now is that she can now follow Australian influences [using the service], get the music that she wants, and find new music just through the service.

Will Rdio have an Australian office?

Scott: Yes.

In Sydney, I suppose?

Scott: We’re looking for some key players. Who’s the best person to hire? Once we find that person, they can determine where the office is going to be. Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth… they’re all options. It all depends on who the best person is to run [Rdio] Australia.

You talked about the ‘a-ha’ moment earlier. For me, when I was testing out the app, that moment was when I realised that Rdio had taken over the iPod player interface on the iPhone [ie the screen that appears when you’re playing music]. I thought that was pretty clever, how similar and familiar that screen was, even though I was using a web streaming service.

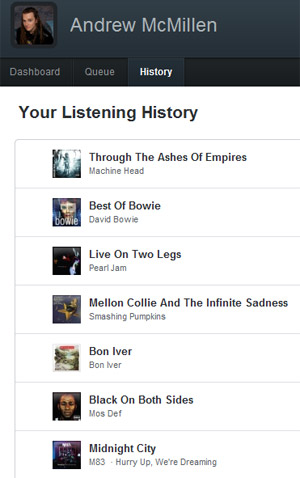

Carter: Two of the most common pieces of feedback we receive: “I just deleted my iTunes collection because I no longer need it,” and “I’ve discovered more music on Rdio in the past two days than in the past two decades”. We’ve obviated a lot of what you would’ve needed iTunes for, and we’ve made it even better with the whole discovery [aspect].

Carter: Two of the most common pieces of feedback we receive: “I just deleted my iTunes collection because I no longer need it,” and “I’ve discovered more music on Rdio in the past two days than in the past two decades”. We’ve obviated a lot of what you would’ve needed iTunes for, and we’ve made it even better with the whole discovery [aspect].

Scott: How we discovered music in our teenager years is we’d go to our mate’s house and you’d wait to hear their song. It wasn’t until you’d heard it a couple of times that you’d go out and buy it. It’s rare that you’d buy a song without hearing it first. That was one of the disadvantages that iTunes has; you couldn’t hear it without purchasing it.

Carter: Every Tuesday, new music comes out [on Rdio]. You don’t have to pay a dollar a song, or eighteen dollars an album: you can play literally everything that’s out on Tuesday. You can save it to your mobile device, you can un-save it and throw it back into the water if you don’t like it. People are consuming more music now. I’ve never seen higher retention or engagement metrics in the 17 years I’ve been doing consumer software, or consumer services. It’s insanely high. People get on it, they love it, they use the hell out of it.

The recommendation worked really well for me. It’s probably a simple thing, but it seemed to work better than most other services I’ve tried.

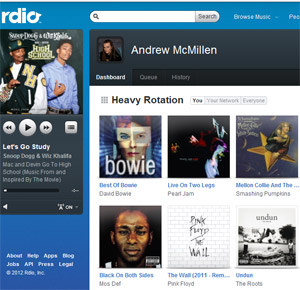

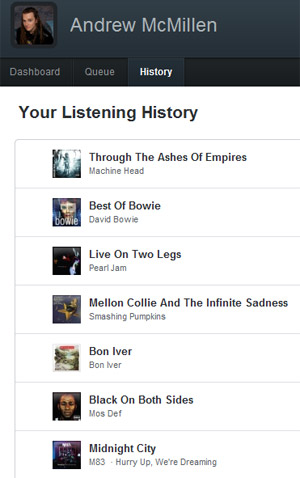

Carter: We wanted to be the most comprehensive service out there. Unlike the other services, we offer a little of everything. We not only have the social music discovery stuff, which is always front and centre, no matter where you dial up the service; we also have the algorithmic recommendations, which you were playing around with. They’re getting better and better every day as we see more data, and learn more about you. We also have the on-demand aspect; “I know exactly what I want to listen to,” whether it’s a song or a playlist. And we have the passive listening stuff; “I like an artist, but I don’t really know which song or album to play. Just play me some of this artist’s songs, and maybe mix in related artists.” Or you can play your ‘heavy rotation’ or your entire collection as a radio station. Or your network’s ‘heavy rotation’, or collection.

In the US… we haven’t carried it over anywhere else because no-one uses it, but we have built our own iTunes store. So you can buy [songs] a la carte in the US, but we found that no-one uses it, because once you’ve used the streaming service, there’s really no reason to buy stuff a la carte.

How does the Australian subscription price point compare to the American version?

Carter: Scott, I’ll let you take that one…

Scott: [laughs] Thanks. The price point is heavily influenced by the rights holders. Between different markets, we have similar… every market to us is the exact same. So the price point basically was just taking into [account] what we had to pay the artists, the labels and publishers. How does it compare? Unfortunately it’s more expensive than the US market. That was just due to market circumstances when we came here. But we personally didn’t treat Australia any different to the US.

How do you pitch the service to fence-sitters? Those people who say they love music, but rarely pay for it. They might go to a lot of shows, but most of the music they download is via torrents and other shady methods, not via iTunes or equivalent stores.

Scott: I think in general, most people want to do the right thing. Music lovers want the artist to get paid. I’ve never come across a music lover that says, “Screw the artist, I want to steal from them”. I think the key is making the service as easy and quick to use that it’s almost the default. So that you’re almost paying for the convenience. Instead of researching on BitTorrent, I have ‘social discovery’ [on Rdio]. I’ve built my playlists around my influencers. I like a particular DJ, and a good friend of mine knows a lot about music, so it just kinda bubbles up [in my playlist]. What used to take me a half hour of reading different music blogs and listening to their tunes, it just comes to me easily, now. As Carter says, discovering more music in two days than in two decades – that is what’s going to engage these music lovers, and make it worth them spending the money that they would otherwise gain through BitTorrent.

Can the service be used offline, or do you have to be connected to a 3G network or equivalent for it to work?

Carter: You can save as much music as you want to your device’s memory card. So if you have a 32gb iPhone, you can save that much. Again, for 34 cents a day – instead of spending $10,000 to fill up your iPhone or iPad…

The mp3s are saved onto the device’s hard drive?

Carter: They’re locally cached, yeah.

Has that been hacked yet?

Carter: Not yet. [laughs]

What are the most common comments you get when people are engaging with Rdio for the first time?

Scott: The people who’re born before 1980, their concern is: “why am I just renting my music? I want to own it; I want to have a collection.” I think that’s just a lack of understanding of the access model. It almost goes back to the heyday of having a massive CD collection, and looking at it, touching and feeling it. But more and more, as that moves on… there are a lot of 21 year-olds who’ve never owned a CD. So that question is more of a theoretical until they start using the service, and then they realise, “Hey, I can hear all my songs, and it’s actually better because I can hear my entire collection no matter where I am, not just in my house.”

Scott: The people who’re born before 1980, their concern is: “why am I just renting my music? I want to own it; I want to have a collection.” I think that’s just a lack of understanding of the access model. It almost goes back to the heyday of having a massive CD collection, and looking at it, touching and feeling it. But more and more, as that moves on… there are a lot of 21 year-olds who’ve never owned a CD. So that question is more of a theoretical until they start using the service, and then they realise, “Hey, I can hear all my songs, and it’s actually better because I can hear my entire collection no matter where I am, not just in my house.”

Carter: I think there’s a general lack of knowledge. Most mainstream consumers don’t understand why they need a service like this, but strangely, they’re already doing it with other types of services, like movies, videos and books. You have a digital book reader; you pull down your books electronically, you don’t have a physical copy. Same with video. They’re getting the fact that, “Oh yeah, this is what I do with other forms of content. Now I have this wide array of connected devices, I don’t need to buy one song for every device.” But I think there’s a general lack of education on why you need the service. I don’t think it’s a resistance, per se.

The desktop client – which is optional to download – has a matching feature, which looks at the music on your iTunes or your computer, and if we have the rights to stream it, it automatically moves it to your Rdio collection. It’s kind of like a locker service, for those people who’ve paid a ton of money – or any money at all – buying digital downloads a la carte. We do that as well. We make it an easier transition.

Going back to what you were just saying about existing libraries; part of my job is being a record critic. It shits me to tears when labels still insist on sending me a CD – which I’ll rip to mp3 immediately anyway – rather than supplying the mp3s so that I can hear the music instantly.

Scott: The industry itself is still in a physical mode. It’s turning around. I get CDs all the time, but I don’t have a CD player. My laptop doesn’t have a CD drive. I can’t rip the CDs. I say “thank you very much” and I usually hand ‘em over to the maid at the hotel. [laughs] It’s a transition period.

Carter: In general, we’re leaving a hit-driven business when you move to services like this. It’s a more personalised view on music. You follow specific people because you like their taste in music. You don’t go to Rdio and look at a ‘top 50’. You go there and you look at what’s relevant, what your friends are listening to. That is a fundamental shift in the industry – along with the mobility [the app allows].

I want to touch on what artists are being paid through Rdio. As I’m sure you’re aware, Spotify had some bad press about how little artists were being paid per-stream. What’s your model like compared to Spotify’s?

Scott: The model’s similar, because the tariff is going to be similar. There’s a couple ways to approach this question. First and foremost, we don’t know about the labels’ relationships with their artists. Those are confidential. I have no idea how the labels are paying the artists. I know the majority of our revenue goes to the rights holders. How that’s being distributed afterwards is a black hole as far as I’m concerned. Having said that, there’s other ways to look at this. Net present value of money and all that other stuff aside, if you buy a [music] download, you only get paid once. That person can listen to that song thousands and thousands of times and you don’t get paid for that. On Rdio, you get paid every single time that song gets played. If it’s a good song, and it goes on for a long time [in terms of popularity], you’ll get paid a lot more than you’ll ever get paid than by a [single] download.

The second way of looking at things is, there’s been cases where artists or labels will pull their music off streaming services off Spotify. It was funny, because this label guy I was talking to – the one I mentioned earlier – was talking to a big artist of his. He turned around and said, “OK, you want me to pull it off streaming for these reasons? That sounds good. So you want me to close YouTube as well, and also the radio?” [The artist] was like, “No no no, keep those open…” The label guy was like, “Hang on a second. You make 200 times more on the streaming service than you do on YouTube, and 150 times more on the streaming service than you do on the radio. So… I don’t understand your reasoning.”

The second way of looking at things is, there’s been cases where artists or labels will pull their music off streaming services off Spotify. It was funny, because this label guy I was talking to – the one I mentioned earlier – was talking to a big artist of his. He turned around and said, “OK, you want me to pull it off streaming for these reasons? That sounds good. So you want me to close YouTube as well, and also the radio?” [The artist] was like, “No no no, keep those open…” The label guy was like, “Hang on a second. You make 200 times more on the streaming service than you do on YouTube, and 150 times more on the streaming service than you do on the radio. So… I don’t understand your reasoning.”

So I think there’s another education [required] on how these [services] can help and build the labels. The actual money pool for these artists, as of 2011 – two months ago? It probably was too nascent, too small to be anything significant to walk away from. However, the way that the ‘hockey stick’ [graph] of digital music and streaming services are going? I don’t think you’ll see those same stories this time next year, because the pie is getting bigger. That is one of the biggest complaints – that dollar-for-dollar, they’re not getting as much from our service as they are from iTunes. But the iTunes pie is a hell of a lot bigger than seven million people worldwide. I understand the gripe now – again, I don’t know what [the artists] are getting from their labels – but if they look at it in a promotional way and also that this is a nascent service and it will grow, you’ll see more and more people come online and stay online.

Carter: In a nutshell, we’re driving up music consumption. Once people are on this service, they’re listening to a lot more music. As Scott said, there’s been a model shift in terms of how they’re paid. So you’ll no longer get paid from only one transaction; you get paid each time you play a song. And we’re driving up consumption. So theoretically, that should even out very soon, as we get to scale. The other part of the equation is, we’re hitting segments of the music value chain that have never paid for music, or only pay $30 or $40 a year through iTunes gift cards. We’re reaching new segments. More people will be paying for music again, as we reach scale.

Scott: And not only that, but the smaller independent labels in each country – because we do worldwide deals – we’ve now given them reach, very quickly and with no cost to the label or artist. In America, in Brazil, in Germany. That exposure can translate into a great opportunity that they’ve never thought of before.

Carter: They can be big in Japan.

Scott: Yeah – it’s not just a t-shirt! [laughs] Going back to our Skype days; when we first launched Skype, we had no idea that Brazil was going to be as big as it was [in terms of users]. It was huge. I’m sure there’s some artists sitting here going, “I don’t know if we can do stuff in Brazil.” Now they’re getting feedback from streaming services and they’re like, “OK, everyone in Brazil is streaming our music, now it makes sense for us to tour there, rather than taking a blind punt.” Or maybe they wanted to go to Rio anyway, which is an understandable blind punt. But this sort of exposure is global, at very, very little cost.

Those are some well-rehearsed answers to a very hard question.

Scott: [laughs] Well, we think about it. It is a concern for us. Because if all of a sudden, the artists don’t want to be on streaming services, we’re in trouble. But we’ve thought about it. It’s an industry-wide discussion.

++

Andrew McMillen (@NiteShok) is a freelance journalist based in Brisbane, Australia.

For more on Rdio, visit their website.

Edit, June 2012: I wrote a feature story for The Global Mail named ‘Unchained Melodies’, which examines the streaming music market in Australia following the launch of Spotify. Click here to read it.

The concept of paying month-by-month to stream music from your computer and smartphone remains a relatively new idea in Australia. In the last year or two, a number of contenders have emerged. Nokia has had their ‘Comes With Music’ service for a while now. Sony launched their ‘Music Unlimited’ product in February 2011. Hulking, canary-yellow retailer JB Hi-Fi launched their own streaming platform in December 2011, dubbed ‘NOW’. BlackBerry, Samsung and Microsoft all have proprietary systems operating in some capacity. Rumours abound of Spotify’s Australian launch. A site named Guvera offers a slight twist on the idea:

The concept of paying month-by-month to stream music from your computer and smartphone remains a relatively new idea in Australia. In the last year or two, a number of contenders have emerged. Nokia has had their ‘Comes With Music’ service for a while now. Sony launched their ‘Music Unlimited’ product in February 2011. Hulking, canary-yellow retailer JB Hi-Fi launched their own streaming platform in December 2011, dubbed ‘NOW’. BlackBerry, Samsung and Microsoft all have proprietary systems operating in some capacity. Rumours abound of Spotify’s Australian launch. A site named Guvera offers a slight twist on the idea:  Scott [Bagby, VP Strategic & International Partnerships; pictured left]: I first came down to Australia to start the discussions at Easter 2011. We were pretty much sewn up by the end of the year. So not quite a year.

Scott [Bagby, VP Strategic & International Partnerships; pictured left]: I first came down to Australia to start the discussions at Easter 2011. We were pretty much sewn up by the end of the year. So not quite a year. Carter [Adamson, co-founder; pictured right]: But seven million music subscribers in a world where everyone loves music? There’s a lot of room to grow. For ten years, we’ve had various fits and starts with digital music: DRM, tethered CDs, and that kind of stuff. We have services like Rhapsody in the US, who are stuck at around 600,000 subscribers. Now within the past year, you have more than a handful of services that have well over a million subscribers apiece. That only happened within the past year. You have markets like Australia, where 40% of all music revenue is digital music revenue. Korea’s over 50%. For the first time, digital music revenue globally is growing quicker [than physical sales]. I think we’re now at an inflection point with digital music subscription services.

Carter [Adamson, co-founder; pictured right]: But seven million music subscribers in a world where everyone loves music? There’s a lot of room to grow. For ten years, we’ve had various fits and starts with digital music: DRM, tethered CDs, and that kind of stuff. We have services like Rhapsody in the US, who are stuck at around 600,000 subscribers. Now within the past year, you have more than a handful of services that have well over a million subscribers apiece. That only happened within the past year. You have markets like Australia, where 40% of all music revenue is digital music revenue. Korea’s over 50%. For the first time, digital music revenue globally is growing quicker [than physical sales]. I think we’re now at an inflection point with digital music subscription services. Carter: Two of the most common pieces of feedback we receive: “I just deleted my iTunes collection because I no longer need it,” and “I’ve discovered more music on Rdio in the past two days than in the past two decades”. We’ve obviated a lot of what you would’ve needed iTunes for, and we’ve made it even better with the whole discovery [aspect].

Carter: Two of the most common pieces of feedback we receive: “I just deleted my iTunes collection because I no longer need it,” and “I’ve discovered more music on Rdio in the past two days than in the past two decades”. We’ve obviated a lot of what you would’ve needed iTunes for, and we’ve made it even better with the whole discovery [aspect]. Scott: The people who’re born before 1980, their concern is: “why am I just renting my music? I want to own it; I want to have a collection.” I think that’s just a lack of understanding of the access model. It almost goes back to the heyday of having a massive CD collection, and looking at it, touching and feeling it. But more and more, as that moves on… there are a lot of 21 year-olds who’ve never owned a CD. So that question is more of a theoretical until they start using the service, and then they realise, “Hey, I can hear all my songs, and it’s actually better because I can hear my entire collection no matter where I am, not just in my house.”

Scott: The people who’re born before 1980, their concern is: “why am I just renting my music? I want to own it; I want to have a collection.” I think that’s just a lack of understanding of the access model. It almost goes back to the heyday of having a massive CD collection, and looking at it, touching and feeling it. But more and more, as that moves on… there are a lot of 21 year-olds who’ve never owned a CD. So that question is more of a theoretical until they start using the service, and then they realise, “Hey, I can hear all my songs, and it’s actually better because I can hear my entire collection no matter where I am, not just in my house.”