An interview with all four members of The Butterfly Effect for The Vine. Excerpt below.

The Butterfly Effect: “I felt that I’d lost everybody’s faith and trust.”

by Andrew McMillen

I arrive at The Butterfly Effect’s rehearsal space in an inner north suburb of Brisbane on the afternoon of Wednesday, 8 February 2012. After pushing open a door bearing the band’s name in bold type, I find all four members in band position, almost as if they’re ready to begin playing. Ben Hall is sitting behind his drum kit, Kurt Goedhart is sitting before a wall of amps and noodling on his guitar, Glenn Esmond is cradling his bass and leaning over his pedalboard, and singer Clint Boge sits at a desk behind a computer and a set of speakers. They’re not rehearsing at the moment, though: instead, these four men are working on a first draft of the setlist for their final tour together. Two days earlier, the Brisbane-based hard rock act announced that Boge will be leaving the band after the tour culminates in early June. The other three members will keep the name, audition to find a new singer, and press on.

Though the announcement was a shock to the band’s significant national fanbase, it’s less surprising when you consider their last few years of activity – or lack thereof, perhaps. Their last album was released in 2008, the sprawling, ambitious Final Conversation Of Kings, which saw the band reaching toward a more epic, prog-rock sound than what we heard on their 2003 debut Begins Here or its superb follow-up, 2006’s Imago. Though the quartet had toured occasionally throughout the last few years – including a short run of dates celebrating their 10th year together, in October 2011 – they had also been trying to produce a fourth album. They still haven’t gotten very far, apparently.

Clint disconnects the speakers on his desk and distributes the milk crates that supported them. Kurt stays more or less in the same spot he was sat when I first entered the room; he continues to hold his guitar, and absent-mindedly plays a few notes occasionally, while the other three position themselves around the desk and do the majority of the talking. It’s clear that Clint and Ben are most interested in having their say, though Glenn does interject with a few nuggets of wisdom throughout our 45 minute conversation. Immediately before the interview begins, there’s an air of friendliness which morphs into tension remarkably quickly, as I start with the most important question: why is Clint leaving, after over 10 years fronting one of Australia’s most successful hard rock bands?

TheVine: How long have you all known about Clint’s decision?

Ben: It’s been a few months.

Clint: September [2011]. It was mid-September when I came in and said I didn’t feel like going on anymore; continuing on. It took a little while to cement in, I suppose.

How did the rest of the band react?

Ben: I think it’d been coming. Everyone knew that there was something that was simmering. Not simmering, but… we’d obviously been trying to make a record for three years, and I just don’t think we were getting very far. I don’t think we were all happy with the way it was going. There was many tense moments, lots of points over those three years where we sat down and tried to realign, and I think it just came to a head on that day. We all agreed that we weren’t in the same direction, so maybe we shouldn’t waste any more time doing that. It was not a decision that was made…

Clint: It wasn’t made lightly. It was something I’d thought about quite a lot leading up to that day. I think it came from… there were a couple of suggestions made to me about who I should work with, and who I should be trying to extract the best melodies with, and not really getting the songs, or delivering them in the right way. That was the last straw for me. I thought, ‘If I’ve lost the faith from my bandmates to produce what I think are the best melodies…’ and to have that trust taken away, then I couldn’t go on working like that. Not only that, but I don’t want to be the weak link in a band. I don’t want to be the guy that’s not pulling his weight. That was another reason, too. I thought, ‘If that was the case, I’ve got to go.’

Not only that, man, but I think musically-wise I was looking for something different that I wasn’t quite hearing in the songs. I [think that some] of the ideas that I [was trying to communicate] weren’t being actioned. They weren’t being done, so I felt lost in that department, as well. It’s probably been happening for some time. I really felt some pressure, to not make the same mistakes that I feel we made on Final Conversation. Wanting to step up and go beyond was the focus.

In terms of the band’s style, you mean?

Clint: Yeah, yeah, and especially my vocal delivery, and what I heard in the songs and what I could hear being the final product. That was all taken into consideration, and the decision was made based on all of those points.

Where were you on that day? Did you meet here [at the rehearsal room], and discuss it?

Clint: Yeah, it was just another practice day, pretty much. I sat in my car for about 20 minutes, pretty nervous, thinking, “This is a big decision to make.” And not only that, to come in and do it cold. I pretty much walked in, grabbed my mic, put it in my pocket… because I thought, “I’m taking my bloody microphone!”

[Ben begins laughing, and says, “Far out!” Glenn laughs and says, “I’m taking my bat and ball, and going home!”]

Clint: [laughs] It was a bit symbolic, but nah, I actually needed it to do something with it. I was going to do some singing at home, and it’s a better microphone than I’ve got at home. I said to the guys, in light of the email that was sent and the two band meetings that happened previously in the year, I felt that I’d lost everybody’s faith and trust, so I removed myself from the band. Everyone took it pretty well. I thought so. There was no, “Fuck you, and up yours Jack” and whatever. “Get the fuck out of here or I’ll bash you,” or any of that sort of bullshit.

Ben: Would’ve made for more of an exciting story, but. We can organise it?

Clint: And also, Benny sent me a text message afterwards and just said, “Look man, you know we don’t want to go out like that.” Which I said to the guys, “I don’t want to go out arguing and screaming, and calling each other names”.

Ben: We’ve done plenty of that over the years. There’s been of that sort of shit going on. It’s not just Kurt and me; it’s Clint and Kurt, or me and Glenn. We’ve had plenty of years worth of fights and all that sort of that shit. The second that Clint walked in, when that was the outcome, I think we all felt that this time, more than any before, that it was probably the right decision. It was probably something that had been coming for a fair while. As much as you don’t want to let it go, you fear having nothing. This band’s everything to all of us. It has been. But you go, ‘Cool, let’s reflect and look at what we’ve done.’

Clint: And celebrate it.

Ben: Immediately, I started to feel a better sense of achievement than I had the whole time I’ve been in the band. We’ve done a lot of stuff together, and we’ve achieved a lot, and it’ll be great to hold this together in light of what we’ve done, and do this tour that’s coming up. Already today, we’re talking about the setlist, piecing it together, and getting excited about it. Which is awesome. It could be a terrible break-up, but everyone’s been adult-like.

Clint: I think that’s the surreal thing for me — when we did that tour in October. That week or two for the [band’s] ten year anniversary. We all came in, the pressure was off of writing an album, and it felt good to hang out. I really enjoyed that tour. [He looks around the room and is met with nods.] I thought everyone got along really well. There was a good sense of camaraderie. There was no hint of any malice towards each other. It was really… and it was odd, because I was expecting being at the airport and being sat in a different section of the plane. Sort of feeling this – ‘Oh shit, I’m the odd guy out’, and having the crew shun me and go, ‘You bastard, you’ve effectively taken one of our meal tickets off the table’ sort of thing. But no, it was good. Everyone was really good. And now it’s — do the last tour, really celebrate and enjoy a long time in the music industry, and some great achievements, and off we go. And then it’s a new singer for The Butterfly Effect, and a solo album for me, and rock’ n roller.

Never before has an album like this been released by a popular Australian rock act. Dark, deep and challenging, Asymmetry is the third album by Karnivool in eight years, and it sees the Perth quintet moving further away from the accessible, pop-like approach to songwriting that characterised its early releases in favour of intricate, unwieldy prog-rock suites.

Die! Die! Die! – Harmony

Die! Die! Die! – Harmony

Jon: Musically, it was very, very heavily influenced by Skeptics, who we were listening to a lot at the time. They’re a New Zealand Flying Nun band, who were quite different again from the Flying Nun crew in the fact that they weren’t using guitars. It was a lot of sample-based shit, a lot of keyboards. They used Euphonics, or E-Sonics … Some fucking early sampler. They just sounded fucking unusual but they also had this edge … [that was] quite majestic, melodically. Hard to explain. Really beautiful, but really weird.

Jon: Musically, it was very, very heavily influenced by Skeptics, who we were listening to a lot at the time. They’re a New Zealand Flying Nun band, who were quite different again from the Flying Nun crew in the fact that they weren’t using guitars. It was a lot of sample-based shit, a lot of keyboards. They used Euphonics, or E-Sonics … Some fucking early sampler. They just sounded fucking unusual but they also had this edge … [that was] quite majestic, melodically. Hard to explain. Really beautiful, but really weird.

Four years before striking it big with their breakout, ARIA-nominated single ‘Don’t Fight It’ in 2008, Perth-based rock band The Panics released their third EP, Crack In The Wall. A stopgap between their 2003 debut LP House on a Street in a Town I’m From and 2005’s Sleeps Like A Curse, its seven tracks saw the still-young band yearning to find a sound of their own. Chief songwriter and singer Jae Laffer is the first to admit that their previous releases sounded like “guys imitating their heroes”, while doing a good job of it.

Four years before striking it big with their breakout, ARIA-nominated single ‘Don’t Fight It’ in 2008, Perth-based rock band The Panics released their third EP, Crack In The Wall. A stopgap between their 2003 debut LP House on a Street in a Town I’m From and 2005’s Sleeps Like A Curse, its seven tracks saw the still-young band yearning to find a sound of their own. Chief songwriter and singer Jae Laffer is the first to admit that their previous releases sounded like “guys imitating their heroes”, while doing a good job of it.

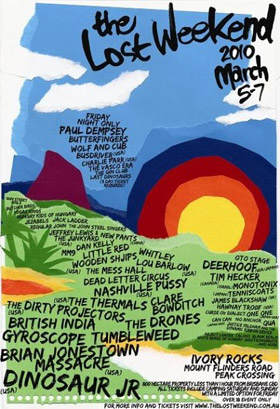

Billed as a three-day camping event located at a conference centre 45 minutes south-west of Brisbane, a 2010 music festival named The Lost Weekend seemed a worthy contender for the interests of Queensland rock fans who couldn’t afford to head south for

Billed as a three-day camping event located at a conference centre 45 minutes south-west of Brisbane, a 2010 music festival named The Lost Weekend seemed a worthy contender for the interests of Queensland rock fans who couldn’t afford to head south for