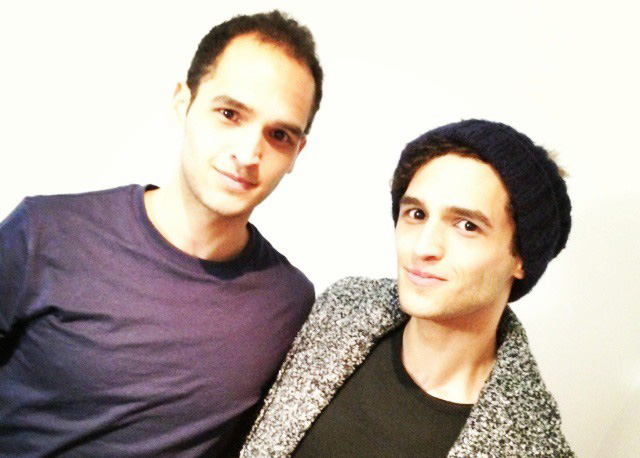

The Weekend Australian Magazine story: ‘Different Strokes: Anthony Lister’, April 2016

A feature story for The Weekend Australian Magazine, published in the April 9-10 issue. Excerpt below.

Renowned street artist Anthony Lister was paid to beautify public spaces – then he was arrested for it.

One of Australia’s great modern artists traipses up and down the inner-city streets of his home town wearing a high-visibility yellow vest atop a white polo shirt and shorts. His tool today is not charcoal, paintbrush or aerosol can but an extendable claw that he uses to pick up rubbish from the footpaths and gutters of Spring Hill, Brisbane. On this gloomy Saturday morning in mid-February, Anthony Lister is performing community service because two weeks earlier a magistrate found him guilty of wilful damage by graffiti in a case brought by Brisbane City Council – which first encouraged Lister to paint its traffic signal boxes in 1999.

The irony of this situation is not lost on a man who rejects the label “artist” in favour of “adventure painter”. Lister donated his time for that council initiative, painting 120 boxes in total. In the years that followed he was paid to paint more of them by the Department of Main Roads, earning him enough to set out on the path to international renown. Yet in an abrupt about-face several years ago, BCC endeavoured to make an example of the artist whose work they once encouraged. This morning, a man whose artistic ethos is to beautify degraded public spaces with paint is now tasked with beautifying them by picking up rubbish.

A middle-aged Queensland Government worker meets the crew, comprising Lister and three fellow community servants, at a Corrective Services building on Little Edward Street at 9am and chaperones them on a winding route through the neighbourhood. Had the government worker typed Lister’s name into Google, he would have found recent news articles which note that Lister’s bold, provocative works hang in the homes of Hugh Jackman, Geoffrey Rush and the musician Pink. He would have seen that Lister’s individual paintings can sell for up to $20,000, that Art Collector magazine has listed him as one of Australia’s most collectable artists, that Complex named him among the most influential street artists of all time and that luxury brand Hermès gave over its window in Collins Street, Melbourne, to a Lister installation last year.

As the community servants pass the Australian Federal Police headquarters and St Andrew’s War Memorial hospital, their black plastic bags grow heavier with each squashed aluminium can and discarded plastic bottle they snatch with their extendable claws. Lister, a boyish 36-year-old and father of three, smiles often and presents an air of playful charisma that infects those around him. He speaks quickly, at a near-manic pace. He is an idealist and an optimist who, in recent years, has taken it upon himself to act as a mouthpiece for street artists.

Past Brisbane Grammar School and the bustling Roma Street railyards they walk, noting the dearth of tagged graffiti that once coloured the walls neighbouring the carriages and train lines; they are now painted a uniform grey. The group tramps past six signal boxes that Lister painted around the turn of the century. They have since been refreshed with other artists’ work, but he remembers them well. There are around 1000 of these throughout Brisbane, and after painting 120 of them for BCC for free, an agreement with the Department of Main Roads allowed Lister to charge $250 a piece for 40 of these paintings, earning him his first $10,000 as an artist and setting him on the path to financial independence.

“He did a tremendous job with the signal boxes and should be commended for it,” says David Hinchliffe, Brisbane’s former deputy mayor, who first commissioned Lister’s work on the BCC boxes in 1999. “He should be given the keys to the city in my opinion.” All up, Lister left his mark and his surname on about 160 signal boxes, turning drab, utilitarian electrical cabinets into unique canvases that added colour and personality to the days of thousands of drivers idling at red lights throughout the city.

In court, Lister admitted that he painted two Fortitude Valley walls, a Paddington skateboard park wall, a city firehose box and a steel garage door in Elizabeth Street. He says that of the five sites, two were painted with the permission of the buildings’ owners, while two were additions to other artists’ works. The charge that stuck related to one of Lister’s iconic faces, drawn on a firehose box in January 2014 in black Sharpie and tagged with his name. The police complaint and restitution reports for each of the five incidents, recorded between 2010 and 2014, show that none was deemed offensive. “If I’d been more criminally minded, maybe I wouldn’t have written my name on the wall,” Lister notes.

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: Jonathan Camí.