A Conversation with Maynard James Keenan of A Perfect Circle, March 2018

An interview with singer and songwriter Maynard James Keenan conducted on 28 March 2018, ahead of the release of A Perfect Circle’s fourth album, Eat The Elephant.

Excerpt of the story I wrote for The Australian:

When the band emerged in 2000, American rock outfit A Perfect Circle was shrouded in intrigue, thanks in large part to a crafty marketing decision. Its debut music video was directed by David Fincher, then known for dark films such as Fight Club and Se7en. His treatment for the song Judith — a dynamic earworm that featured soaring slide guitar melodies and pointedly anti-religion lyrics — offered only fleeting glimpses of the band’s five musicians performing in an empty warehouse.

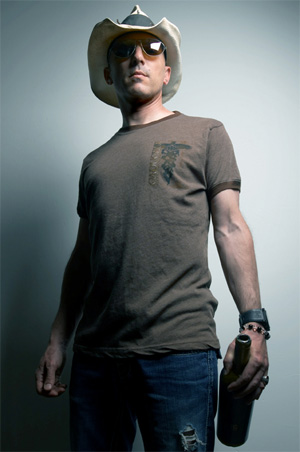

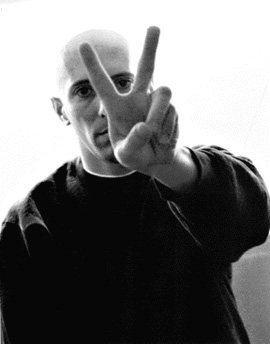

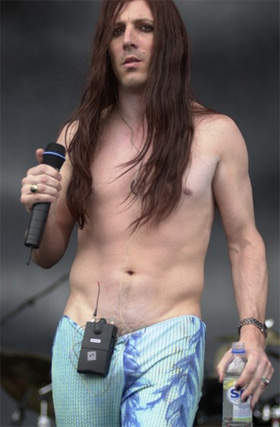

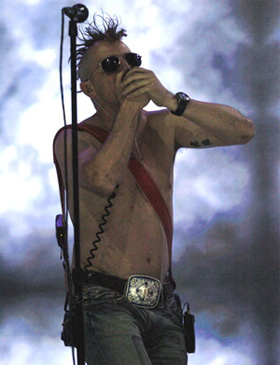

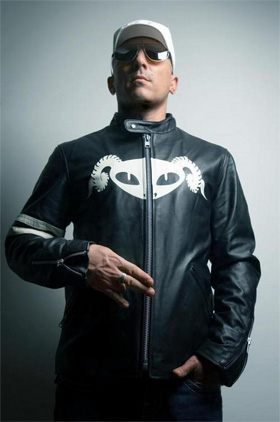

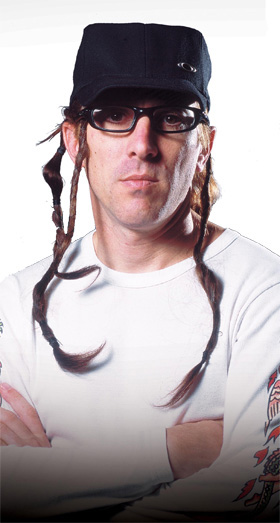

In Maynard James Keenan [pictured above centre], the group possessed an uncommonly powerful singer who also fronted hard rock outfit Tool. With his new project, Keenan took to wearing long, braided wigs in promotional images and on stage, perhaps in part to differentiate his persona from the one he inhabited in Tool, where he tended to prefer a bald scalp and an occasional fondness for body paint.

Judith was a deeply personal song for the singer, as it was named after his mother, who suffered a cerebral aneurysm in 1976 that left her paralysed and restricted to a wheelchair for the rest of her life. Through it all, her faith in a higher power never wavered, which her son found confounding.

“Fuck your God / Your Lord and your Christ,” Keenan sang. “He did this, took all you had and left you this way / Still you pray, you never stray, you never taste of the fruit / Never thought to question why.” Its chief vocal hook contained just six words dripping with irony: “He did it all for you.”

It was an explosive introduction to the world and its message resonated. A Perfect Circle’s first album, Mer de Noms, achieved the highest debut position for a rock band on the US Billboard charts, where it sold 188,000 copies in its first week to reach No 4. The group released a second album of original music in 2003, then went on hiatus following an album of anti-war cover songs that was released on the same day as the US presidential election in 2004, when George W. Bush won a second term.

To read the full story, visit The Australian.

The full transcript of my interview with Maynard James Keenan appears below. I previously spoke with the singer in 2010 and in 2012.

++

Publicist: I work with Maynard and A Perfect Circle. Before I put him on the line, I just wanted to make sure that they told you that he’s only talking about A Perfect Circle, not his other art. The other thing I should mention is: he doesn’t discuss specific lyrics. If you bring up specific lyrics, he’ll just tell you that it’s open to interpretation, but he discusses the bigger themes of the record.

Andrew: Hi, Maynard. Where in the world are you at the moment?

Maynard: I’m in Los Angeles at the moment.

Are you in rehearsals? What are you doing over there?

Just working, I’ve got a few things I gotta tidy up before we go on the road.

Very good. Congratulations on the new album, I’ve spent a reasonable amount of time with it so far, and as someone who has listened to A Perfect Circle since the first album, it’s really pleasing to hear great new music from you guys again.

Oh, thank you.

I want to start by asking you about [band co-founder] Billy [Howerdel], a man with whom you’ve had a long and fruitful creative partnership. What do you love about working with Billy?

He has a freshness. He’s not afraid to throw out ideas, and he’s not afraid to hear me criticise them, or praise them, or adjust them, or move with them. So it’s a great working relationship because there’s no… there’s not a lot of ego. There’s just a lot of work, there’s a lot of to and fro, and listening to each other.

You have both watched each other evolve as artists, since Billy first showed you some of his songs many years ago, which formed the basis of A Perfect Circle. What have you noticed about how his approach to writing and arranging music has changed during that time?

I feel like he’s less focused on sounds, ‘cause back in the day, new gear, new toys, new pedals… he seems like he’s a lot more focused on the melody in the song, and the core.

I’ve read that Billy writes by himself to get a song “to a place where I’m not embarrassed by it anymore, then present it. And then usually Maynard writes to it.” What do you find appealing about this method of working?

Well, provided he’s open to it shifting from there, it basically comes down to the core melody. Because he’s really good at that, coming up with the melodies, I tend to strip it down to that. [laughs] Poor guy. He puts all this work into all those layers of stuff, and I start muting things. But at the end of the day, he did it right to begin with, he just was second guessing, and adding things. But it’s better you have a guy who cares, than a guy who doesn’t, right?

Definitely. This is your first album recorded with Jeff Friedl and Matt McJunkins in the band. What do they bring to the table that helped with writing and recording Eat The Elephant?

I just like those guys. It’s a good working relationship with them. We’ve been touring with them, with Puscifer and with A Perfect Circle for years now. They’re just a good, solid rhythm section, live. Any ideas and adjustments you have for Jeff, he’s such a seasoned player, he understands and can execute, so it’s great.

You’ve played with some fairly monstrous rhythm sections during your career. Where do you place Jeff and Matt, in that sense?

Oh, I wouldn’t. I think they stand on their own, in their own way. I would never dare compare all those people. They all bring their different flavours to the table. It’s been an honour to work with all of ‘em.

I read that you wrote three songs [from Eat The Elephant] around Christmas time, during a particularly productive 36 hours. I wondered: what are you like to be around when you’re in that kind of writing headspace?

I’m not sure that that’s accurate, but we’ll go with it. In general when you’re writing, it comes in all flavours. You’re gonna have some things that come easy; there’s gonna be some things that take a little more effort, and more focus. It’s really inspiring when you have a moment where something comes together within 24 or 48 hours in a way that you don’t have to go back and meddle with. The trick is to have a few people around you that have a little bit more perspective. I think that’s the hard part: being able to walk away and trusting that it’s done. A painter who’s not willing to put the paintbrush down, that’s the hardest part of painting. Put the brush down; walk away.

Well, that detail of the three songs, which were The Contrarian, Disillusioned and Eat the Elephant: I took that detail from a Kerrang article, I think, that said you wrote them all quite quickly. Did you want to clarify what the actual time period was?

Um, you know, 36 hours is a rough guessestimate. It could have been 72; it could have been 12. But it was a short period of time, comparatively.

That idea of knowing when to put down the paintbrush: do you think you’ve gotten better at knowing when a song is done, as you’ve written more songs?

No, I think that’s always going to be a struggle, knowing when to stop. I would imagine that you get better at it, but I still feel like it’s a hard thing to do. One of the hardest things to do.

Has writing lyrics always been a purely solitary activity for you?

Not necessarily. I think to really hone it in, you definitely need a quiet space to do that. I’m sure when you’re writing an article, you don’t like to do it in the middle of a busy room. You definitely need to go in an office, or your room, or somewhere there’s no distractions. It’s no different. Having a little bit of focus always helps to get those things to go forward.

Do you find that lyrical ideas ever come to you prior to hearing any music, or do you strictly let the music itself inform the subject matter?

The melodies and the rhythms inform the syllables, the cadence. So the song itself, the core element of the song is going to dictate where the melody goes. And then I try to figure out what that melody suggests. And then find a keyword, and build on it.

In that sense, how important are song titles to you? Do they come early or late in the process, generally?

Both, as in a song could have the song title first; that dictates most of where things go, or a particular word doesn’t really fit in the song, but it is the core of the song, so it has to become the title, otherwise there’s no place to put it. And without it, you might be lost.

This album has what I think must be the longest song title… or maybe not.

Oh, there’s longer.

I’m thinking of the Fish title. [So Long, And Thanks For All The Fish]… although you’ve got the Counting Bodies Like Sheep… title as well. Was that an easy decision to make, to name a song such a lengthy phrase?

Yeah, I mean, there was definitely a specific reason, but I think it’s kind of contained within. Always breadcrumbs, right?

When writing lyrics, are you open to spontaneity and unexpected inspiration, or do you have a one-track mind once you decide what a song means to you?

All of those things. If you have a one-track mind, and it’s not working, you better change that, or it’s not gonna work out. But if you have an idea and you want to try to fight through it, because you feel like it’s worthy of fighting through, take it as far as you can. If you can’t, then: abandon ship.

I believe you’re fond of driving while listening to instrumental mixes, then pulling over to write lyrics as the ideas come to you. Is that correct?

Depending on the situation, yeah, I’ve been known to take long drives, or just sit in the car, or just sit with the headphones on in the cellar. I put music on while I’m working on the barrels. Usually it’s just those unconscious moments help, where it’s just on; you’re not thinking about it.

How long has that approach of driving while listening to mixes been a part of your writing process?

Forever. The drive can be metaphorical; it might just be a long walk, on a plane. Those quiet moments.

How conscious are you of the audience in those moments, when you’re writing by yourself somewhere? Do you ever give a thought to what will sound cool when thousands of people sing along to your lyrics at a concert?

Never. No. The song comes first; you just have to worry about the structure and rhythms of the song, and if it’s translating. Then it’s up to somebody else as to whether they feel that I’m successful in it, after the fact. If I feel like I’ve completed the mission and gotten the point across, then I’m happy. But it’s never about what jumpsuit I’m gonna wear for what song. No, never.

Fair enough. Do you recall which song from the new album you found it hardest to write to?

There’s always one, right? Just the simple math, there’s gonna be one that’s harder than the rest. But I can’t off the top of my head think of which one that would be. Not at the moment, yeah. I’m drawing a blank.

Well, to put it another way, then. Do you recall which song went through the most revisions from the time that Billy initially sent the musical idea to you?

Oh, jeez. All of them. Yeah, they all evolve so much. Then we go down blind alleys, turn around and come back. Yeah, I don’t know. They all go through so many changes, and those changes can be quick, it might be like we mentioned; it could be that the music went through a million changes and all of a sudden, the lyrics came almost overnight, once it was settled.

You’re unique as a lyricist in that sense that you juggle writing for three different, popular bands. Do you have any personal rules or criteria that you use to determine whether a thought or idea would be best expressed through each of these outlets, and not the others?

No, never. It’s all about the music. It’s all about conversations. The way you speak to your mother is far different than the way you speak to your college roommate, or a bartender, or the mailman. You just honour those conversations that are in front of you; those subject matters, that music, it’ll all take that direction.

Have you ever found a situation where a lyrical idea initially felt at home with one of those projects, but ended up being published in another context?

Not usually, no.

Thinking of the new album again, is there a song where you’re particularly proud of your vocal performance?

I don’t know about ‘proud’. You know, pride comes before the fall. Am I happy with what we achieved? Yeah, I think we hit the mark on some of the intended approaches. I think the things that I’ve learned in every project have preceded the next. Every album, every EP, you just learn as you’re going. You learn different approaches, and I think it kind of keeps you fresh. If you just assume you’re starting over, and yet you’re still drawing on some experience.

What about The Contrarian? That one stands out to me, because you’re reaching for some tones and hitting notes I’ve never heard you sing before.

Guess you haven’t heard Puscifer, then.

No, I certainly have.

A bunch of that stuff you might think is Carina, that’s actually me.

Oh, shit. Okay. I might have to go back and re-listen, then.

Ah huh.

Thank you for that. I’m particularly fond of your vocals on Delicious. That one seems like it’ll be pretty fun to perform live, right?

Yeah, I think there’s a lot of those are gonna lend themselves to live performance. I think a lot of ‘em are going to be more difficult to pull off, but I think the ones that are most difficult to pull off live are probably going to be the most compelling, I would think. Just because if you can pull it off in a live setting, and it resonates in a way that you’re not used to hearing in a live setting, that can be more powerful than an obvious rocker.

Your voice is heavily treated with effects in Hourglass, which I can’t recall happening on too many other songs with A Perfect Circle – correct me if I’m wrong. What inspired this decision, to warp your voice like that?

That’s what the song called for. Again, you just have to be open to what you’re hearing, and make sure you’re honouring it, in a way, right?

I read an interview with Billy from 2013 where he said that he considers By And Down The River to be one of his top three or top five A Perfect Circle songs. Would you agree with that?

[laughs] I don’t know. Yeah, if that’s how he feels about it. A lot of times, that’s just because it’s a new thing you’ve done, and you’re excited about it, so it feels like the best thing you’ve done. But I think they all have their merits. Again, what were the goals? What ideas were you trying to express? I always kind of look it that way: what was the puzzle? Did I achieve my goal for this particular puzzle? If the answer’s ‘yes’, then it’s as important as any other puzzle I’ve solved, or supposedly solved.

Have you always thought about your work in that sense of puzzles, or is that a new idea?

No, it’s always been puzzles. It’s always been, there’s a melody, and there’s an idea, and I gotta figure out how to match up a conversation to yourself, to somebody else, to a group of people and match it up to that energy. How do you do that? What words do you use? What words don’t you use? How do you accurately tell that story, so that it maps out an emotional path for you, that you can retrace. All those puzzles are important to pay attention to.

Well then, looking back at A Perfect Circle’s catalogue, what do you think the first album represents, in terms of puzzle?

Oh, I would never, I would never, I would never discuss that. That’s up to you. For me, that’s a personal puzzle. I’ve solved it. Your experiences with it, that might be a completely different experience. I would never, never want to rob you of that experience, whatever it is that you’re having. To map it out too much… I feel like nowadays, with the big blockbuster movies, the whole movie’s in the trailer, and you just go for the popcorn, I guess. I don’t know. But I would never, I would never want to take that away from you. I don’t like previews.

Me either. Especially with something I’m going to see, like the new Star Wars. Why the fuck do I need to see a trailer? I’m going to be there. Don’t spoil anything for me.

Yeah, I mean that was the beauty of seeing [the film] Three Billboards [Outside Ebbing, Missouri]. I didn’t know anything about it. I walked into the theatre, I saw the names Frances McDormand and Sam Rockwell, and I just dove in. I didn’t care; I just wanted to see what those artists and those masters were going to do. And I had no idea what I was walking into. It blew me away.

I’m very mindful of what you said about not wanting to unpack the puzzle, as it were, and that was an impertinent question. Apologies for trying to…

Oh, you’re fine. I get it.

I wasn’t trying to get you to answer any long-standing riddles, or any shit like that.

Oh, no no. But those things come up, and depending on how you ask them, I can derail it. It’s fine. [laughs]

Yes, you’re a professional in that sense.

[laughs]

I was thinking of Thirteenth Step in particular, because that one had a thematic thread in that twelve songs, twelve steps, and all that kind of thing. Maybe that puzzle was more easily accessible to the average listener than the others.

I think there were puzzles on it that weren’t understood. I think if you look at that album in general, it’s almost like when you look at a cast of characters. Everybody has their role, everybody has their lines and their personality, and you wouldn’t have a decent movie with an arc, or some conflict and resolution, without some contrary steps, and contrary people opposing each other, or not understanding each other. And I think Thirteenth Step, a lot of the songs are sung from and written from various perspectives. They’re people who don’t understand each other. They’re not all from one perspective, and they’re not necessarily… when they seem to be pointing the finger, it might be a song about a person who points fingers, and who’s doing it without compassion.

So a lot of my stuff is that. It’s not necessarily sung from the perspective of me preaching this position. It might be me taking the role of a person who doesn’t understand, in order to bring you a full, balanced cast.

I guess that’s something that’s often overlooked and mistaken by casual listeners, who tend to assume that songwriters are always from their own perspective. That must be a bit frustrating to be misinterpreted in that sense.

I mean, it’s only frustrating if you explain it, and they just look at you like you’ve just tried to sell ‘em a fart. That’s the only… if they don’t get it, if they’re just too dumb to get it, that’s rare. There are some dummies in the universe. We elected one. Oh shit, did I go there? But generally speaking, people get it. Once you explain it, they go ‘Okay, I see’. So I’m rarely frustrated in that way. It takes explaining, I guess, but I don’t like to explain too much of that, ‘cause again, I don’t want to rob the experience.

I suppose that probably comes out of your own being a fan of music. You probably didn’t expect David Bowie and Joni Mitchell to explain their art. You just took from it…

Never, no. I would imagine half the stuff that… when Joni starts talking about music, my eyes glass over, ‘cause she’s an incredibly intelligent crazy person. So you want to avoid having her explain the songs, ’cause they’re beautiful just like they are. There are definitely some deeper nuances to them, but I don’t need to know the math.

Well, sticking with that idea of Billy’s top three songs, would you be so bold as to suggest any of your particular favourites? Or you don’t think in those terms, when it comes to A Perfect Circle.

Yeah, I couldn’t really comment. Again, they were all a particular puzzle, and maybe there have been some in hindsight that I thought that I’d solved, in a way, but didn’t. I think there’s some that I think are beautiful, in that I can’t do them anymore. They were written for a person with a 27 year-old throat, not a person with a 53 year-old throat. So some of those songs are, in a way, they’re kind of a time machine song. I think it’s important for an artist to evolve and grow, especially because your body changes. Not just your perspective, your experiences, but I think it’s important to pay attention to that. The idea of hopping around on stage like you’re 22, at the age of 53, is kind of… pathetic? I don’t know.

Well, you’ll be going on tour in a few weeks. Sticking with that idea of the throat, how has your approach to live performance changed as you’ve gotten older?

Oh, you understand that you have a perishable instrument. So you have to pay attention to it, and respect it. I think had I respected it a few years earlier, there might be some flexibility in it, that I used to have. But singing incorrectly, incorrect diet, shitty sleep, not enough water, all those things you just take for granted as a kid, you know? But that’s the nature of youth, isn’t it? Frivolous.

Well, maybe with that idea of songs you can’t perform anymore: I note that Judith has been absent from the setlist for quite a few years. Is that because the band is uninterested in playing it, or because it’s hard to sing?

My mom asked me not to.

Fair enough. I mean, you can’t possibly give a better answer than that, so thanks very much.

Yeah. Mom knows best.

I went back and watched the video for Judith, which I think remains one of the strongest debut music videos I’ve ever seen. And in that clip, the faces of the band members were only show in fleeting glimpses, and it’s interesting to compare it to the recent video for The Doomed, which consists of nothing but shots of your five faces. Was this a conscious decision by you and the band, to draw a parallel between those two videos? Or am I reading into it too much?

Oh, you’re probably reading into it, but again, I don’t want to rob you of that experience. If that’s how you feel, that that’s the approach, I’d love to take for credit for something like that. I’m cool with it. [laughs]

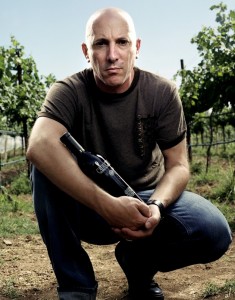

You’re clearly fond of both making music and making wine. Do they both give you a similar sense of pleasure and satisfaction, or do you think of them rather differently?

I think there’s quite a bit of grounding that comes with both. I think there’s a little more… there’s a little bit of humility moreso in wine making, because Mother Nature doesn’t really give a fuck about your plans. So you’re definitely having to adjust and readjust when it comes to the wine making. I think there’s more similarities for me than there are differences, just because of my approach to taking what’s there in front of you and working with it, and working around it; working with it, massaging it, highlighting what’s there, rather than trying to force your will.

Finally, Maynard, thinking about your broader career: is there anything strange or unexpected that has come out of dedicating your life to music?

I think that’s just not the way I’m wired. I guess the fan thing is always odd to me. I’m just trying to find my way, and for you to elevate somebody who’s not necessarily social; not necessarily figured it out – that seems odd to me. My father and my mother both taught me some level of humility. I think it’s important, but I do also acknowledge that there’s an embrace… We’re a society that embraces spectacle, in a way. We just don’t know any better, and we elevate people beyond their human limitations, and expect more of them than they can actually deliver. And if they are truly broken, they gobble it up, and act holier, I guess.

I don’t think of myself like that. I’m often disappointed when people do that, and then they read the disappointment as being holier-than; no, that’s not what I’m saying [laughs] I don’t understand why you would need an autograph, or a photograph, or any of those things. If you want it from me, walk across the hall or across restaurant, across the wherever to a complete stranger and ask them for an autograph, and a photograph, to see how they react to that request. Their reaction is probably my reaction: like, why? That’s weird. Who are you? What do you want?

Well, it was a pleasure to speak with you. Best of luck with the tour, and have a great year.

Thank you, sir.

++

Don’t ask about Tool. Don’t ask about A Perfect Circle. Definitely don’t ask when Tool’s next album – their first since 2006’s 10,000 Days – is due. These are the publicist-stated rules of engagement when interviewing Maynard James Keenan, frontman of those two bands and also Puscifer, a “multimedia project” that encompasses music, film, performance, wine and clothing, and has released two albums so far: 2007’s V Is For Vagina and 2011’s Conditions Of My Parole. Keenan is touring the Puscifer show outside of North America for the first time in February 2013, with three Australian theatre shows booked around his commitments with A Perfect Circle at Soundwave Festival.

Don’t ask about Tool. Don’t ask about A Perfect Circle. Definitely don’t ask when Tool’s next album – their first since 2006’s 10,000 Days – is due. These are the publicist-stated rules of engagement when interviewing Maynard James Keenan, frontman of those two bands and also Puscifer, a “multimedia project” that encompasses music, film, performance, wine and clothing, and has released two albums so far: 2007’s V Is For Vagina and 2011’s Conditions Of My Parole. Keenan is touring the Puscifer show outside of North America for the first time in February 2013, with three Australian theatre shows booked around his commitments with A Perfect Circle at Soundwave Festival. It sounds like a set-up to a bad joke. What happens when you combine Californian progressive metal band Tool, a couple of entrepreneurial Brisbane men in their mid-30s, and wine made high in the Arizona desert?

It sounds like a set-up to a bad joke. What happens when you combine Californian progressive metal band Tool, a couple of entrepreneurial Brisbane men in their mid-30s, and wine made high in the Arizona desert? An interview with

An interview with  Did you enjoy the process, though?

Did you enjoy the process, though? These days you say yes to a few more things, maybe not everything. Would you call that maturity or just a realisation that sometimes it’s okay to share some things?

These days you say yes to a few more things, maybe not everything. Would you call that maturity or just a realisation that sometimes it’s okay to share some things? We have?

We have? As an artist, you value art. Has that feeling become stronger?

As an artist, you value art. Has that feeling become stronger? I see. Well, since you don’t necessarily have an album to promote this time around, will you be constructing a set list a little different to last time?

I see. Well, since you don’t necessarily have an album to promote this time around, will you be constructing a set list a little different to last time?

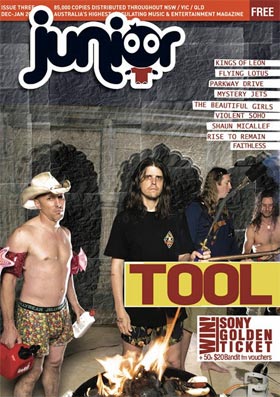

With their potent combination of distinctive, heavy instrumentation and singer Maynard James Keenan’s singular voice, they’re perhaps the only rock band who were able to push back against a crumbling record industry and opt for quality over quantity. Including their 1993 debut full-length,

With their potent combination of distinctive, heavy instrumentation and singer Maynard James Keenan’s singular voice, they’re perhaps the only rock band who were able to push back against a crumbling record industry and opt for quality over quantity. Including their 1993 debut full-length,