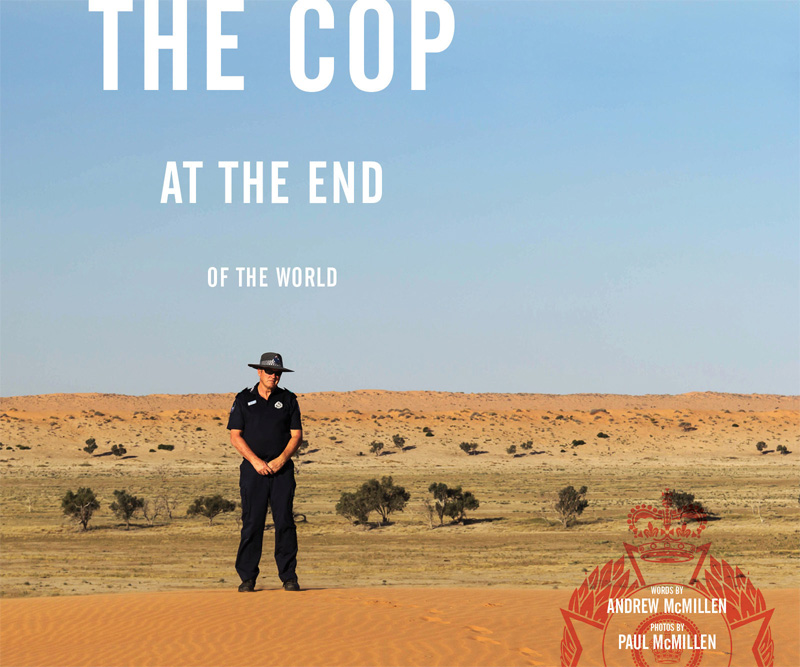

BuzzFeed story: ‘The Cop At The End Of The World: Neale McShane’, November 2015

A feature story for BuzzFeed, published in November 2015. Excerpt below.

The Cop At The End Of The World

The longest serving officer at Australia’s most remote police outpost, Neale McShane is about to retire. But first, one last big weekend watching Birdsville, population 80, become an unlikely — and ill-suited — tourist destination.

On a map of Australia, Birdsville is situated toward the middle of the country, yet its remoteness is so absolute that it might as well be on another planet. Established in 1881, the town abuts the edge of the Simpson Desert, an enormous expanse that consists of more than 1,000 sand dunes. That a town was built here at all is testament to either human willpower or outright folly. It is not quite self-sufficient, as most goods are either trucked in via hundreds of miles of snaking gravel tracks dotted with roadkill kangaroos and carrion birds, or flown in via the twice-weekly mail service.

On windy days, the red dust from the desert blows across the town’s few dozen buildings, adding a fine film of rusty grit that bonds itself to every surface. On hot days — which is most of them — bush flies revel in the stark stillness, incessantly seeking out the moisture of sweaty human skin.

In Birdsville, if you want to buy a coffee, you have one option: the Birdsville Bakery. If you want to visit a restaurant, you have one option: the Birdsville Hotel. If you want to buy alcohol, you can do so from either place. If you fall ill, you’ll be treated at the Birdsville Clinic, and flown nearly a thousand miles to the state capital if you can’t be fixed there. If you want to buy basic groceries, you’ll have to settle for whatever Birdsville Roadhouse has in stock. If you want to see a film or live music, you’re in the wrong town. Birdsville State School has five students. The kindergarten has three. There are no teenagers. There is no crime. There is, however, a police station. It is manned by an officer who chooses not to carry a gun, because he has no need to.

The police station is situated at the edge of town, a short walk up the main street, toward the pub, the combined grocery store–cum–fuel station, a tiny airport, the school, and the clinic. When the airstrip’s runway-lights system is switched off at night, a stroll along this route reveals the breathtaking volume and variety of stars overhead, which flicker brightly, knowingly, free of all light pollution. Shooting stars are seen more often than cars on the main street, which might be used by 30 vehicles on a busy day.

For most residents of Queensland, Australia’s second-largest state by area, Birdsville will only ever be a geographic curiosity seen at the edge of the map on the nightly weather report. Locals say the population is 80 people, half of whom are Indigenous Australians, but the sign posted outside of town notes that the population is “115, +/- 7,000.” After driving over a thousand miles to be here, seeing that sign somehow quickens the pulse. Once a year, during the first weekend of September, this sleepy desert town sparks to life, relatively speaking.

To read the full story, visit BuzzFeed. Above photo credit: Paul McMillen.