In a five-part series, Andrew McMillen will examine the digitally-inspired shift in consumer habits away from the long-established album format. He begins with the history surrounding the album, and the hints at the consumer unease that has led to its reduced importance within the remodeled recording industry.

Cast your mind back 10 years.

As a music fan in 1999, you’d read music magazines and listen to the radio to garner information regarding upcoming releases from your favourite artists. You’d talk about your expectations and predictions to your friends in person, and strangers online. You’d hear the lead single on the radio and see it on the television a couple of weeks before the album was due. You’d visit your favourite record store on launch day and pay $20-30 to own the compact disc containing an act’s latest music and artwork.

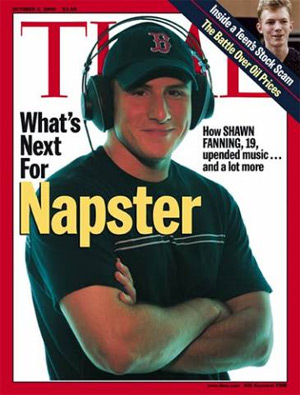

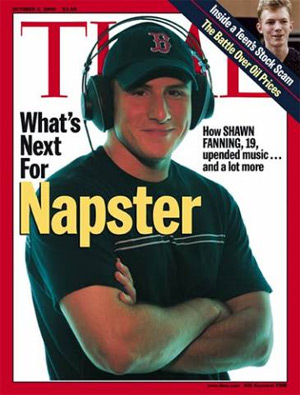

Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0.

Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0.

1999 was the year that the recording industry was irreversibly changed by Napster, which circumvented the needs of millions of music fans worldwide. No longer were we forced to travel to a record store during business hours in order to buy a CD. Instead, we could download the audio in passable quality from our homes, burn the data onto a blank CD, and freely distribute these recordings to our friends.

The recording industry’s response to the Napster quandary is well-documented elsewhere, and it’s not the focus of this series of columns. Instead, we’re investigating the history of the album, which is commonly known as a recording of different musical pieces.

But why the album? How come we’re so used to artists releasing a collection of ten to fifteen songs every couple of years, comprising between 30 and 80 minutes of music?

It first appeared a hundred years ago. Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker Suite was released by the German label Odeon in 1909. The first album in the history of the recording industry comprised four double-sided 78 RPM discs, and was sold in a collection that resembled a photo album.

These recordings were a big deal at the time. You could use a record player to listen to music in your home, at your leisure! Crikey!

Then came the 33 1/3 RPM vinyl discs known as LPs. Short for long-play, LPs were first mass produced by Columbia Records in 1948 and came in two diameters: 10- and 12-inch. The latter format was initially reserved for premium-priced Broadway theatre and classical recordings, while popular music appeared solely on 10-inch discs. This early discrepancy in the history was caused by record company executives, who misjudged the commercial appeal of non-Broadway and classical recordings. By the mid-1950s, the 10-inch LP was discontinued. It reappeared in the late 1970s as extended-play mini-albums, which are also known as EPs.

Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side.

Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side.

The LP format could contain up to 45 minutes of music, which was divided into two sides. Record labels and recording artists were faced with a new window of opportunity, wherein they were no longer confined to a series of four minute-long creations. Once the format gained market dominance, musicians and producers realised that they could use continuous playback to maintain elements of style and mood between songs, or to promote thematic continuity in the form of concept albums.

As the record industry matured, LPs were no longer just a collection of singles released in a streamlined format in order to increase sales. Decades of ‘single’ releases led to ‘album-as-art’ aesthetics, wherein the industry’s stakeholders – musicians, listeners, and labels alike – came to rely on innovative, creative uses of the LP format.

By the 1960s, record companies were employing artist and repertoire (A&R) representatives to approach emerging acts with recording contracts. These were commonly known as record deals, wherein an artist or band would agree to record an album – or series of albums – that the record label would subsequently sell and promote.

And therein began the rot.

As the record industry became comfortable with the album format, they sought out the acts most likely to help them sell their products. The compact disc (CD) format was ushered into the market in 1983; annual sales in the US rose from 800,000 in the first year of production to 288 million by 1990, and almost 1 billion per year by the turn of the century.

But after being seduced by major labels’ reputable names and marketable reach, artists found themselves locked into increasingly-shortened ‘write, record, tour’ schedules. This was the dream of musicians the world over, sure. To make a living from writing, recording and touring their music. But few would have dreamed of comprising their artistic vision, or rushing to complete unfinished material in order to meet a label’s release schedule.

As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores.

As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores.

This was the era of the widely-quoted figure: for every successful album, a major label released nine failures. But these businesses could afford to buy musical talent en masse and sign these emerging songwriters and performers to an album-release contract, then drop them if their commercial appeal faltered.

Rarely were artists afforded time to find their feet and cultivate their best material; not with the clock ticking, the recoupable expenses climbing, and the label’s stakeholders demanding quarterly growth figures. No way!

Of course, I’m painting an exaggerated picture on a slightly-skewed canvas. There have been success stories on both major and independent record labels throughout the history of recorded music. But the latter were all but hidden from the view of the average music consumer, who only paid attention to the acts who were charting near the top on radio and television and playing arenas.

For decades, the recorded music industry revolved around the album: the record deals, the release schedules, the pricing structure, the touring cycle, the album reviews, the catchy lead single that’d inspire consumers to purchase the album. But ten years ago, Napster-induced cracks began to appear in the established business model.

From the Walkman to its brother, the Discman, and from the burning of CDs to the rise of Apple’s iPod, the digital generation ushered in a massive shift in music consumer demand. Next week, I’ll highlight portable playlist control as a key component in the reduced reliance placed upon the album by music consumers.

Brisbane-based Andrew McMillen writes for several Australian music publications. He can be found on Twitter (@NiteShok) and online at http://andrewmcmillen.com/

(Note: This is part one of an article series that first appeared in weekly Australian music industry magazine The Music Network issue #744, June 29th 2009. Read the rest of the series: part two, part three, part four and part five)

To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first.

To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first. That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s.

That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s. In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept.

In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept. Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0.

Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0. Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side.

Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side. As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores.

As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores.

I wholly echo the above sentiments.

Do I only nominate to review bands that I find enjoyable or interesting? Absolutely. Only once have I accepted an assignment to review bands that I was less than interested in; that show resulted in an unexpectedly enjoyable experience.

The overarching theme that many seem to forget is that all discussion of music is subjective. Preference and taste vary between listeners. This isn’t going to change. Bleating to everyone within earshot that Band X or Band Y are great or shit or relevant or geniuses or ugly or brilliant or immature or talentless or irrelevant or (adjective) isn’t going to change an individual’s preference.

Sure, it’s fun to mock those who listen to The Presets, but I’m being facetious when I do so and don’t devote more than a moment’s thought to the listening choices of those around me. My listening habits have been on display since October 3, 2004. My experimentations, lamentations and guilty pleasures are all there (*cringe*). Do I listen to music that you think is shit? Most definitely. Does this concern me? Certainly not.

I don’t have time for that. It’s hilarious that others do. It’s also interesting to note that musical discussions tend to evoke strong, passionate feelings within many of us.

Within music journalism, there exists a consistent and inelastically large market in idiot-baiting. Thanks for reminding us, Everett.

(footnote – I’ve listened to The Presets quite a bit. I liked their early releases a lot, but their latest is a stinking pile of shit that I never want to hear again.)