The Australian story: Hillsong Music Australia, October 2011

A short feature for The Australian’s arts section about Hillsong Music Australia, the record label arm of the Hillsong Church. Excerpt below.

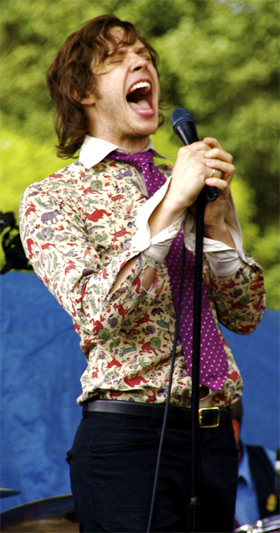

[Photo above: Hillsong Live plays at the Sydney Entertainment Centre in December. Thousands of fans attend Hillsong’s conferences and live album recordings each year. Picture: Trigger Happy Images Source: Supplied]

The crowd roars as the lights dim. All eyes are focused on the stage, where smoke obscures the silhouetted figures. Four guitarists, four singers, two keyboardists, a drummer and a dozen-strong choir break into song. The sound is loud and clear. A boom operator swings a camera across the front rows; its images are fed on to three screens, which also list the song’s lyrics in a huge white font.

The visual aids seem superfluous, though, as most know these songs by heart. Once the strobe lights disperse at song’s end, one of the singers asks: “Does anybody love Jesus here tonight?”

It’s Friday night at the Brisbane campus of the Hillsong Church, yet the production values wouldn’t be out of place at the Brisbane Entertainment Centre, about 25km away. About 3500 worshippers surge through these doors each weekend for services on Friday nights and Sunday mornings. The first third of this 90-minute service is more rock show than sermon: there are about 600 people in attendance tonight, all grooving on the spot to the rhythm section, hands held aloft in praise, voices singing, “Our God is greater than all”.

All the musicians on stage are volunteers, as are the sound and lighting technicians. But unlike other live music venues across Brisbane, there’s no pursuit of a pay cheque. Instead, we’re witnessing musical expression in search of divine approval.

After the band leaves the stage, an advertisement for Hillsong’s annual live album recording appears. This year, the recording takes place at Allphones Arena in Sydney, where 15,000 people are expected to attend. Hillsong Music Australia manager Tim Whincop calls the recording — to be held this Sunday — “an extension of our church services”.

“With so many services across a weekend, we don’t often get chance for our whole church to worship together at the same time,” Whincop says. “Our gathering at Allphones Arena will allow us to achieve this, and we will take this opportunity to record our next worship album.”

Since its first album in 1988, Hillsong Music has become one of the most successful independent record labels in Australia. According to Whincop, the label has sold more than 12 million records worldwide, and more than one million records in Australia. It has 21 ARIA-certified gold records to its name, 11 certified gold DVDs and one platinum CD: the 1994 live album People Just Like Us, which sold more than 70,000 copies. Yet, apart from when it pops up in the charts a handful of times each year, the label exists outside the nation’s mainstream music industry.

Hillsong Music emerged in 1983 out of the congregation at the Hills Christian Life Centre in Baulkham Hills, Sydney. Whincop says its music interests have grown from “a small team of passionate people to a group of hundreds of singers, musicians, songwriters and production volunteers” based at three campuses in Sydney, one in Brisbane and 12 extension services held in venues including bowling clubs, universities and cinemas.

Hillsong Music Australia — a department of the church — employs 17 full-time staff.

Its artists and repertoire have little in common with other labels. Where a company such as Dew Process in Brisbane has a diverse roster of artists, such as Sarah Blasko, the Panics, Mumford & Sons and Bernard Fanning, Hillsong has just three bands on its roster: Hillsong Live, Hillsong Kids and United, the church’s best known “praise and worship band”, which was founded in 1998 and has 13 albums under its belt. Like the Hillsong Live series, United releases an album each year. The label’s next release has a Christmas theme.

Though Whincop refuses to discuss Hillsong Music’s earnings — “We don’t talk specifically about wages and music sales outside of what is published in our annual report” — the record label is one of the church’s biggest income sources. According to its annual report, Hillsong Church Australia last year earned $64 million, with total assets of $28.7m and income from conferences at $6.7m.

“In 2010, the albums released through Hillsong Music ranked in the top 10 on the iTunes charts in a number of countries including the US, where it achieved sixth position,” the report says. “In Australia, we also achieved the No 3 spot on the ARIA charts.”

Whincop, who joined the church 10 years ago as a weekend trumpet player, says overseas album sales make up about 90 per cent of sales. “We have a strong following in the US, UK, South Africa and South America, and also have a very strong presence in many of the European and Asian nations,” he says. In recent years, Hillsong has drawn the ire of the local industry because of its apparent attempts to secure high ARIA debuts by coinciding album releases with the church’s annual conferences. These well-attended events help drive up sales. In 2004, the live album For All You’ve Done caused a stir by becoming the first Hillsong album to debut at No 1. It stayed in the top 100 for 11 weeks.

“It is no secret that we gather together large groups of people every year at conferences and events such as the album recording,” Whincop says.

“Contrary to media reports, this is not a marketing scheme but it is at the very heart of the Christian church coming together in unity to worship God and is at the very heart of what we do.”

Nick O’Byrne, general manager of the Australian Independent Record Labels Association, says Australian record labels treat Hillsong as an oddity.

“Their business model and the music they release doesn’t really exist in the same realm,” he says. “It’s not like (record labels) consider themselves in competition with Hillsong. I don’t think (labels such as) Dew Process, Liberation or Modular fight over artists with these people. They don’t get into bidding wars for the next United album.”

Asked about high ARIA chart debuts coinciding with Hillsong conferences, O’Byrne says: “They do game the charts, but I wouldn’t want that to seem like they’re rigging the system in any illegal way. Because they’re not. Everyone tries to somehow game the ARIA charts by taking advantage of sales conditions.

“If you have a tour or a big gig, you try to release music around that to achieve the highest spot on the ARIA charts. They just have a tighter, close community that guarantees more sales.”

Hillsong is not immune to one of the biggest issues facing the music industry in recent years: decreased sales and revenue as a result of online file sharing.

Hillsong’s annual report for last year says its margins on album sales continue to decline because of the soaring Australian dollar and increasing numbers of digital downloads.

“We still have a large problem with piracy,” Whincop says.

“I think this generally stems from the lack of education in the market of the effect of file-sharing and the lack of understanding in younger generations that it is actually illegal.”

O’Byrne admires the way the label has found a way to thrive in a bubble, charting high before fading away until its next release.

“They’re smart,” O’Byrne says. “If you look at their websites, and the way they present themselves, and their engagement with social media, they’re not behind the times. They’re definitely proactive. A lot of their success has to be attributed to the fact they are trying to run a modern, flexible record label. They’re not sitting there, waiting on old business models. They have great YouTube channels and they communicate really well with their audience. They’ve set themselves up like a good label should.”

For the full story, visit The Australian. [Note: you may have to register for an account to read the full article, as News Limited has imposed a paywall as of October 2011]

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world.

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world. Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think.

Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think. First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

The Beggars Group music blog strategy filters down to indie labels like Sydney’s

The Beggars Group music blog strategy filters down to indie labels like Sydney’s  Beyond Remote Control, EMI Music have maintained

Beyond Remote Control, EMI Music have maintained  Australian indie label

Australian indie label