Ryan Holiday is one of the most influential people in my life.

His blog, RyanHoliday.net, is one of the most valuable online resources I know of. This is a statement that I know will make him blush, because Ryan is a modest guy. I know this because when I first approached him for an interview in January 2010, he deflected my questions – which were extremely detailed, potentially to the point of exhibiting stalker-like behaviour. He wrote that when he felt he deserved an interview, he’d give it to me; he also said that mine was “the most in depth, investigative email I’ve ever gotten”.

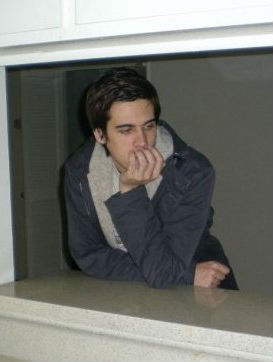

At 24, Ryan [pictured right] is a year older than me. I’ve viewed his blog as a kind of counsel since I first became aware of his work. His thinking and writing has, in turn, shaped my thinking and writing. It is fair to say that I wouldn’t be on the path I am now if I hadn’t been closely studying another young male on the other side of the world, fearlessly kicking down doors in search and pursuit of his goals. For a couple of years, Ryan’s ambition, persistence and confidence all directly influenced my day-to-day thoughts and actions. Which is another statement that will make Ryan blush, because it’s a pretty fucking weird thing to type, let alone think.

Ryan first attracted my attention by attracting the attention of someone who I was closely studying at the time: Tucker Max, the American blogger-turned-author who is best known for his 2006 book I Hope They Serve Beer In Hell and the 2009 film adaptation of the same name.

Ryan wrote a review of Tucker’s website – which, at the time, was a collection of stories about Max’s drinking and sexual exploits – for his college newspaper, and sent the link to the author. Soon after, Max posted the review on his message board, which was a fairly popular corner of the web; it was deleted a couple of years ago. I immediately became interested in figuring out who Holiday was.

That review led Tucker to hire Ryan as an intern at his company, Rudius Media (now defunct). It led Ryan to work with the acclaimed author Robert Greene as a research assistant on the strategy book The 50th Law, co-written with rapper 50 Cent and released in 2009. And it led Ryan to be hired by the clothing manufacturer American Apparel, where he worked as Director of Marketing for a couple of years. He still works as an advisor to American Apparel, but moved from Los Angeles to New Orleans in mid 2011 to work on a book project of his own.

Since January 2007, Ryan has consistently used his blog as a platform for discussions about writing, running, online PR, media, philosophy, and stoicism, among other topics. I’ve consumed every word that he has written since his first post, ‘The Business Of Running‘. I often re-read his posts multiple times, which is something I rarely do online. That first post remains a valid starting point for understanding Ryan’s way of thinking and writing. I’ll quote the opening paragraph below.

“I run 5 miles every night. It’s where I go to digest my day, hash out the multitude of information that’s been poured into me in the last wild six months or so, and to try and condense it down to some sort of cohesive strategy to live my life by.” – Ryan Holiday, January 31 2007

When I visited the United States for the first time with my girlfriend Rachael in September 2010, I asked to meet up with Ryan in Los Angeles. We met at a burger joint on Melrose Avenue and talked for an hour or so. It was a huge thrill for me to meet a guy who’s been something of an internet hero to me for nearly five years. Rachael didn’t really understand why it was so important to me at the time.

Neither did I, really, now that I think about it. All I knew then, and know now, is that Ryan Holiday is one of the most influential people in my life. It’s an honour for me to publish the below email interview.

Andrew: When you wrote that review of Tucker’s website, what was the intended outcome?

Ryan: I’m not sure if I ever told anyone this, but I’d noticed that Tucker tended to link to or write about any press he got (at least back then) and so I thought, “I’m a writer for a college newspaper, why don’t I try it”? It didn’t really go much further than thinking about it at that time. Then a couple weeks later I had the opening line of that piece floating around in my head: “If Hunter S Thompson had read this site, he probably wouldn’t have killed himself.” I figured I had something and eventually sat down and wrote it.

So the intended outcome was that I’d send it to him and he’d link to it (I reposted the article on my blog) and that would be it. But the reaction totally blew my mind. Within about 20 minutes he’d responded and… I went back to my Gmail and found it:

From: Tucker Max

[November 28th, 2005]

“Jesus Christ. Dude, that is fantastic. Seriously, I am awed by your grasp of me and my material. I am going to post this as THE example of a great review of me and my work.”

It’s funny to me now because that reaction has become a pretty routine occurrence for me since then. I obviously thought I wrote a pretty good article but I was still reluctant to send it off. Is he going to like it? Did I go overboard? What are the chances of it getting a response? Turns out I had nailed the target and didn’t quite understand the extent. That seems to happen a lot to me. You’d think I’d anticipate it by now, but still other peoples’ reaction (positively, anyway) tends to catch me by surprise.

What did that response change for you? Was that one of those ‘Fight Club moments‘ I remember you writing about years ago?

I think it was the opposite of one of those moments. I think of a Fight Club Moment as something that breaks you down and demolishes the pretense and bullshit entitlement you have in your life. This wasn’t that. It instilled a lot of confidence in me. It was like, “ok, I am better than I knew. That’s awesome, maybe I can build on this.”

I think it was the opposite of one of those moments. I think of a Fight Club Moment as something that breaks you down and demolishes the pretense and bullshit entitlement you have in your life. This wasn’t that. It instilled a lot of confidence in me. It was like, “ok, I am better than I knew. That’s awesome, maybe I can build on this.”

What happened next between you and Tucker?

I think after he had the publisher send me a copy of his book to review, which I did, and after it was published I asked for his thoughts on the writing. He went over it on the phone with me about ways I could improve my voice and tone.

I stayed in touch—I think in my post about advice a couple weeks ago I called this ‘staying on the radar’, and that’s basically what I did. I would pop in and ask questions, for advice, send links etc. Any excuse I could think of to keep that connection alive. Only an idiot would waste that chance.

A year or so later I was in New York, where he was living and I told him I wasn’t looking for a job, or a salary or a handout but I had some thoughts on ways I could contribute to his company, Rudius Media. After the meeting, he offered me an internship, which 6-8 months later become a job. But it was all a very fluid thing, like I was saying.

[Andrew’s note: that post he mentioned, ‘Advice to a Young Man Hoping to Go Somewhere (Or Get Something From Someone Successful)‘, is an absolute must-read.]

To me, the act of writing the review and showing Tucker is a pretty solid example of figuring out what you want, and pursuing it accordingly. Correct me if I’m wrong, but didn’t that lead to him offering you a job, you quitting college and moving to LA, and then working for American Apparel?

Haha, I mean you pretty much figured out exactly what I was doing or trying to do with the last question, probably with a better sense of clarity than I really had at the time. But yeah, it was the door that ultimately led to the opening of all the other doors. I have him to thank for all of it. When I see a path to an opportunity–like a lane in basketball–I sort of put my head down and the next thing I know I’m through it and it took me somewhere I didn’t totally anticipate.

With the Tucker thing, I knew I wanted to one day be a writer like the kind of writers he was working with at the time – I’d known this since I first saw his sites in high school – so I did that article, and then I was working for him, and then I was working for the people he was working with, and then the people they were working with, and so on. I don’t think any of them every solicited me for a job either so much; it was just that I was around all the time, doing stuff and offering to do stuff, and then it eventually became official.

How did you come across Robert Greene’s work? Was it Tucker who first showed you?

Yeah, I’d heard of the books obviously but I think Tucker recommended The 48 Laws of Power so I read it. I marked up my copy so much and had a million questions to ask Tucker.* Then the first time I met him, Tucker walked me to a bookstore and bought me The 33 Strategies of War and said, “if you’re going to work for me, you’ll need to have read this.” I think that’s how I found out I got the job. All I took from that exchange was: “I better read this book on the plane ride home and know it backwards and forwards.”

Yeah, I’d heard of the books obviously but I think Tucker recommended The 48 Laws of Power so I read it. I marked up my copy so much and had a million questions to ask Tucker.* Then the first time I met him, Tucker walked me to a bookstore and bought me The 33 Strategies of War and said, “if you’re going to work for me, you’ll need to have read this.” I think that’s how I found out I got the job. All I took from that exchange was: “I better read this book on the plane ride home and know it backwards and forwards.”

* Ryan’s sidenote: that copy of The 48 Laws is priceless to me. Someone stole it out of my office at American Apparel. I was fucking distraught. It makes no sense because Dov [Charney, AA chairman and CEO] has a million copies laying around. Why would they want my marked-up personal copy?

How did the opportunity to work for Greene arise?

The three of us – Tucker, Robert, and I – had lunch in L.A. a few years ago and it kind of arose from that meeting. Although it almost didn’t, because I was so nervous I accidentally messed up when I gave Robert my phone number.

I have a suspicion that working on The 50th Law might have inspired a sense of validation, given your regular documentation on your life via the blog, and your personal reading and research via your Delicious account. Am I right, or way off?

I mean, it was very cool to have the privilege to be allowed to peek inside of project like that. But I don’t think validating is the right work. What it was was educational, from top to bottom. Researching for someone–particularly someone like Robert–is crazy because you get pointed in all these directions that you’d never have gone by yourself, given a very firm objective to gather from that direction, and a tight deadline with which to do so. When you read or research for yourself, it is kind of this wandering, directionless thing. For the book, it was like getting a crash course in a million different subjects. I was interested in all of them so I would mark down the stuff I would want to go back and look at later.

So it’s funny, when I see the book, it reminds me of loose ends I still need to tie up for myself and am interested in looking into.

Your stoicism guest blog for Tim Ferriss in April 2009 attracted a lot of attention. What did you get out of it? What did you learn from the experience?

More than anything, it helped me clarify my thoughts. Tim is awesome and he’s got a very impressive commitment to expanding the scope of blog all the time. He starting writing about productivity and got all these people hooked and the next thing you know he’s totally revolutionized how they think about health and science. I was lucky that he gave me the microphone for one of those digressions.

I got quite a few new readers out of it and he also was gracious enough to give me two more chances to write about similar topics. [‘The Experimental Life: An Introduction to Michel de Montaigne‘, October 2010; ‘Looking to the Dietary Gods: Eating Well According to the Ancients‘, July 2011]

What you learn in a setting like that is how to tailor your message to different mediums. When I write for my site, I can be as self-indulgent as I want. When you write for someone else or on a bigger platform, you have to be much clearer and you have to catch them right from the beginning. They’re not YOUR readers, so you have to meet them where they are if you’d like to bother listening to your message. At the same time, it taught me that I don’t want to have to perform like that all the time which kind of freed me up to not have to chase acquiring that audience for myself. If didn’t learn that, I’d be spend all my time working to build something that at the end of the day, would make me miserable to have.

Could you tell me about your working space?

When I was in LA, I had a big office with 5-10 employees at any given time at the American Apparel factory. I had an office at my house at well.

Now, in New Orleans, I sort of went in the completely opposite direction. I’m in a studio apartment so I don’t work much there. I like working and reading and writing out of the library at Tulane or, I belong to an old school athletic club in the French Quarter that has like a library/parlor work space that I use.

On Mondays, I try to do all my administrative stuff—conference calls with employees, meetings, paperwork and then during the rest of the week I respond to AA emails in the morning and again at night. The middle of the day is mine. I try to write, go to the gym (run, box or swim), and read—in that order.

I still have the same quote, the one from Marcus [Aurelius], above my desk:

“When you wake up in the morning, tell yourself: The people I deal with today will be meddling, ungrateful, arrogant, dishonest, jealous and surly. They are like this because they can’t tell good from evil. But I have seen the beauty of good, and the ugliness of evil, and have recognized that the wrongdoer has a nature related to my own – not of the same blood or birth, but the same mind, and possessing a share of the divine. And so none of them can hurt me.”

The other quote above my desk is from Seneca:

“Some lack the fickleness to live as they wish and just live as they have begun.”

In November 2007 , you wrote that “you have to be happy with you”. I understand it’s a work in progress, but are you happy with you in October 2011, nearly four years later?

Happier for sure. It’s not so much that it’s a work in progress as it is a process. I forget who said it, but someone smarter than me said that “happiness ensues, it cannot be pursued”. And I think it was Aristotle who said that happiness was the result of excellence.

Either way, I take that to mean that you’re happy when you are doing whatever it is that you’re doing, well. So: are you doing well at your career? Is your relationship the best it can be? Are you handling adversity or a difficult experience with excellence? Are you behaving honorably? Etc etc.

These are all opportunities to excel in the moment and cumulatively these moments create a sense of happiness. I’m fucking 24, there’s no way I’m doing well all the time at everything but I do feel I am getting better and more consistent.

I want to close on a cliched question, which I hope you’ll humour me on. What advice would you give to yourself five years ago, when all you really knew about yourself was that you ‘wanted to one day be a writer like the kind of writers Tucker was working with at the time’?

Fucking breathe. It’s not as precarious as you think it is. There’s no need to be anxious. See, it’s really easy when you’re that young and you don’t have a safety net to think you have to cling to everything for dear life, everything is a crisis, everything is mission critical, nothing else can be the priority.

Fucking breathe. It’s not as precarious as you think it is. There’s no need to be anxious. See, it’s really easy when you’re that young and you don’t have a safety net to think you have to cling to everything for dear life, everything is a crisis, everything is mission critical, nothing else can be the priority.

When you’re in that space, it’s really hard to have the patience and compassion or even empathy for the other people in your life because you’re fucking fight or flight all the time. In reality, it’s not as dramatic as all that. Taking a more relaxed and accepting approach might mean losing a couple opportunities here and there but down the road, you end up turning down plenty of those anyway, so what does it matter if a couple never arrive?

If I told myself this and really listened, I feel like I’d have been happier along the way and be able to be prouder of how I behaved and the decisions I made.

++

For more on Ryan Holiday, visit his blog. Hopefully he’ll soon post some news about the publication and release of his first book.

[Edited on November 18: the first news of Ryan Holiday’s book has been announced.]

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as

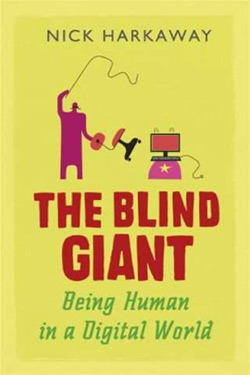

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as  Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

I think it was the opposite of one of those moments. I think of a Fight Club Moment as something that breaks you down and demolishes the pretense and bullshit entitlement you have in your life. This wasn’t that. It instilled a lot of confidence in me. It was like, “ok, I am better than I knew. That’s awesome, maybe I can build on this.”

I think it was the opposite of one of those moments. I think of a Fight Club Moment as something that breaks you down and demolishes the pretense and bullshit entitlement you have in your life. This wasn’t that. It instilled a lot of confidence in me. It was like, “ok, I am better than I knew. That’s awesome, maybe I can build on this.” Yeah, I’d heard of the books obviously but I think Tucker recommended

Yeah, I’d heard of the books obviously but I think Tucker recommended

Fucking breathe. It’s not as precarious as you think it is. There’s no need to be anxious. See, it’s really easy when you’re that young and you don’t have a safety net to think you have to cling to everything for dear life, everything is a crisis, everything is mission critical, nothing else can be the priority.

Fucking breathe. It’s not as precarious as you think it is. There’s no need to be anxious. See, it’s really easy when you’re that young and you don’t have a safety net to think you have to cling to everything for dear life, everything is a crisis, everything is mission critical, nothing else can be the priority.

Similar anxieties were expressed by Patrick, a 24-year old part-time radio producer who barely sees his partner, Adam, since their schedules rarely align. Yet Patrick admitted “I do get a pang of sadness” when the pair were home at the same time, but both absorbed in their individual computer screens. The author dubs this being ‘together alone’.

Similar anxieties were expressed by Patrick, a 24-year old part-time radio producer who barely sees his partner, Adam, since their schedules rarely align. Yet Patrick admitted “I do get a pang of sadness” when the pair were home at the same time, but both absorbed in their individual computer screens. The author dubs this being ‘together alone’.