The Guardian story: ‘School’s out early for overworked and undersupported young teachers’, August 2013

A story for The Guardian Australia; my first for the website. Excerpt below; click the image to read the full story.

School’s out early for overworked and undersupported young teachers

Nearly half of all teaching graduates leave the profession in the first five years, Monash University research has found

Close to 50% of Australians who graduate as teachers leave the profession within the first five years, many citing overwhelming workloads and unsupportive staffrooms as their main reason for leaving the job, according to new research.

The apparent exodus of early career teachers is a significant drain on resources, says Dr Philip Riley, of Monash University’s faculty of education, who is leading Monash’s research into the reasons that lead to young educators resigning at an alarming rate.

“It’s costing the nation a huge amount of money. It’s just a waste, particularly when we’ve got so many threats to the funding of education,” he says.

Riley estimates that between 40% to 50% of “early career” teachers – defined as recent graduates with less than five years of practical experience – ultimately seek work in another profession, a nationwide figure that’s consistent with research published in the UK and US.

The most frequently cited reasons for teachers leaving aren’t related to the traditional complaints of difficult student behaviour or mediocre salaries. Instead, Riley’s research – currently unpublished, with a view to publish later in 2013 – pinpoints unsupportive staffrooms, overwhelming workloads, and employers’ preference for short-term contracts as the main areas of tension.

“Graduate teachers feel relatively well-prepared to deal with difficult kids, although that can be hard,” says Riley. “Young teachers tend to go into schools highly optimistic and full of energy, but if there’s no one to take them under their wing and help them through those first couple of years, they get very disillusioned. The smart ones start to imagine an easier future doing something else.”

The estimates in Riley’s study are supported by the Australian Education Union and highlight a system in crisis. “It’s a very demanding profession,” says the AEU federal president, Angelo Gavrielatos. “Workloads and stress are both high. Teachers remain undervalued, underpaid and overworked.”

This scenario rings true for Nick Doneman, a 28-year-old based in Brisbane. He graduated with a bachelor of education from Queensland University of Technology in 2007. “I really enjoyed my degree,” he says. “My practical experiences [before graduating] were really good. But all of that died quite quickly when I saw that the job wasn’t so much about teaching as it was about being a parent. That was a huge turn-off for me. I felt like classroom teaching was only 25% of the job – the rest was dealing with kids and all their issues, the things that go on between them and their parents, and behaviour management, as well as paperwork.”

Doneman says he got “thrown from school to school” upon graduating; he took several short-term contract jobs, teaching English, Film and Television, and Social Science, but found it difficult to attain full-time employment. His contract stints involved travelling to schools in and around Brisbane, including Kenmore, Bray Park and Carbrook. He found that it wasn’t the kind of job where you could go home at the chime of the three o’clock school bell with a clear head, either.

“It involved a lot of work in the afternoons and on the weekend, if you wanted to do the job properly,” he says. “It’s easy to be a bad teacher, and not plan ahead of time what you’re going to teach.”

In each staffroom, Doneman looked around him and found that very few teachers could relate to the young graduate’s initial passion for making a difference to students’ lives.

“The majority simply did it as a job,” he says. “They didn’t feel like they had the responsibility to do any planning outside of work. I couldn’t live like that, doing a crappy job. There was no teacher at any of those schools where I looked at them and thought, ‘I like what your life looks like’.” After three and a half years, Doneman threw in the towel, went back to university, and now works as a paramedic.

To read the full story, visit The Guardian.

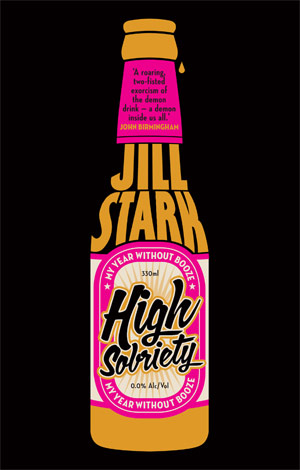

Scottish-born journalist Jill Stark was a health reporter with a blind spot: despite writing about Australia’s binge-drinking culture for The Age newspaper, she would regularly drink to excess, as she’d done since her teens.

Scottish-born journalist Jill Stark was a health reporter with a blind spot: despite writing about Australia’s binge-drinking culture for The Age newspaper, she would regularly drink to excess, as she’d done since her teens.