The Monthly story: ‘Chalking The Walk’, May 2013

A story for The Monthly in the May 2013 issue – my first contribution to the magazine, in ‘The Nation Reviewed’ section. The full story appears below; the illustration is credited to Jeff Fisher.

On a Tuesday morning in March, 80-odd young people wearing red T-shirts hopped off two buses in Lismore, in northern New South Wales, and began canvassing shoppers and retailers in the central business district. Their quest, as declared on their chests, was to help end extreme poverty. Not in Lismore per se, but globally, by petitioning the federal government to bump up its foreign aid spending.

The team was one of many converging on Canberra from around the country, as part of “The Roadtrip”, a week-long campaign organised by the Oaktree Foundation, the youth-run group that also arranged the MAKEPOVERTYHISTORY concert in 2006. About eight hundred “ambassadors” were taking part all over the country. Their aim was to gather 100,000 signatures, or around 125 each, over the course of the trip via a smartphone app.

The target didn’t sound overly ambitious. But, by noon, many of the locals out and about in central Lismore had been approached several times. Some were starting to get ticked off. “We’re actually irritating people now,” noted a group leader, Tammy, and the entire team retreated to a McDonald’s restaurant, where the buses were parked. One overweight team member was in tears. A local woman had accosted her, shouting: “If you stopped eating at fuckin’ McDonald’s, there wouldn’t be any poverty!” The canvasser’s peers moved in to soothe her. “That’s really rude,” someone countered.

Three days earlier, the volunteers, aged from 16 to 26, had met for the first time at the University of Queensland in Brisbane to undertake an intensive course in political campaigning. Most were university students; a handful were still in high school. Ebony from Townsville was a champion skateboarder pining for her board. James, 21, was a soccer-mad Scot. Emily Rose, a petite redhead, showed off an unnerving party trick: the ability to dislocate her limbs at will. Each had stumped up $400 to cover food, travel and accommodation costs.

The ambassadors had been taught some handy lines: “The door to ending poverty is opened by thousands”; “Two-thirds of the 1.3 billion worldwide living in poverty are our neighbours”; and “Australia’s fair share is just 70 cents in every $100 to fight global poverty”. This last line was central to the campaign. In 2000, Australia agreed to adopt the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals, aimed at reducing extreme poverty. This meant setting aside 0.5% of Australia’s gross national income for foreign aid by 2015 (recently put off till 2016) and 0.7% by 2020. Currently, the nation contributes 0.37%.

“The government has made a commitment,” the Roadtrip ambassadors pitched to shoppers. “We’re here to keep them true to that.” At night, the team slept rough in local church and sports club halls. By day, when not canvassing or on the buses, the team courted the local media, debriefed, attended further campaigning lessons and enjoyed “personal energising time”, as spare hours were denoted on the itinerary. Some members worried that they were falling behind on their petition targets. “Relax, it’s not about the signatures,” said a group leader. “It’s about the movement.”

The day before they were in Lismore, the team had detoured briefly to the retirees’ paradise of Bribie Island, where half the group “chalked the boardwalk” with messages – “Help keep the promise of a fair share!” – while the other half were assigned the task of “painting the town red”, by asking local businesses to display campaign posters in their shop windows.

Many shop owners were charmed enough to comply. “I don’t think they’ll achieve anything, but good luck to them,” a 74-year-old manager said. A girl serving ice-cream next door could barely remember the pitch – “something about foreign aid?” – but said she assented to their request because “they were young, and looked like they were important”.

Wyatt Roy, the 22-year-old local MP, joined the ambassadors for a barbecue lunch. Wearing sunglasses and a crisp white shirt with rolled-up sleeves, he stood on a picnic table and said, “In this job, very often do people come to me with problems, and very rarely do they come with solutions. Thanks so much for doing what you’re doing.” As the team left Bribie, a sudden downpour washed away the chalked messages. The ambassadors coasted into Canberra two days later, via Kempsey and Port Macquarie, late on Wednesday afternoon, with 47,000 digital signatures.

The next morning, at seven o’clock, the various busloads from around the country assembled at Parliament House. A giant map of Australia had been painted on the lawn, and the eight hundred ambassadors stood within their respective state boundaries. Chanting slogans, they made a lot of noise. Greens MPs hung around. A cherry picker was on hand so that TV crews and Oaktree’s media team could take shots from above. Bob Carr, the foreign minister, addressed them. “We are on target for 0.5%,” he said, before turning and gesturing behind him. “It’s up to you to persuade everyone in that building that they’ve got to act!”

Scores of meetings had been scheduled between ambassadors and their local MPs, but many representatives either cancelled or sent staff in their place. Julie Bishop, the shadow foreign minister, slated to speak at the morning assembly, sent her apologies, too.

The bus trip home, via Sydney, was a long one. A question kept coming up: had they actually made a difference? Was Wayne Swan, the treasurer, any more inclined to heed their call to increase spending on foreign aid by a third, to 0.5% of gross national income? His sixth federal budget will answer that, on 14 May. No one is holding their breath.

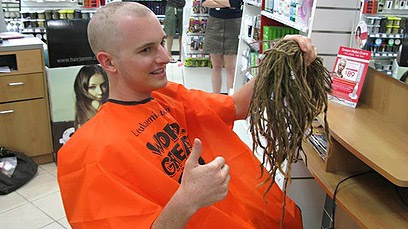

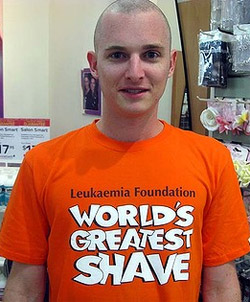

I’ve never regretted the decision, though seven and a half years of growth – coupled with the gradual thinning and breaking of the locks on top of my head – meant that it was always going to be a finite style.

I’ve never regretted the decision, though seven and a half years of growth – coupled with the gradual thinning and breaking of the locks on top of my head – meant that it was always going to be a finite style. I love how hair can become a social object; a topic of conversation, a reason to interact with another human. Those with dreadlocks know this better than most. It’d surprise you just how many people are curious enough to stop us in the street and ask to touch our hair. (Just as common: “is that your real hair?”)

I love how hair can become a social object; a topic of conversation, a reason to interact with another human. Those with dreadlocks know this better than most. It’d surprise you just how many people are curious enough to stop us in the street and ask to touch our hair. (Just as common: “is that your real hair?”)