Good Weekend story: ‘The Whistleblowers: Australian football referees’, July 2014

A feature for Good Weekend, the colour magazine published with the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age each Saturday. This is my first story for the magazine. Excerpt below.

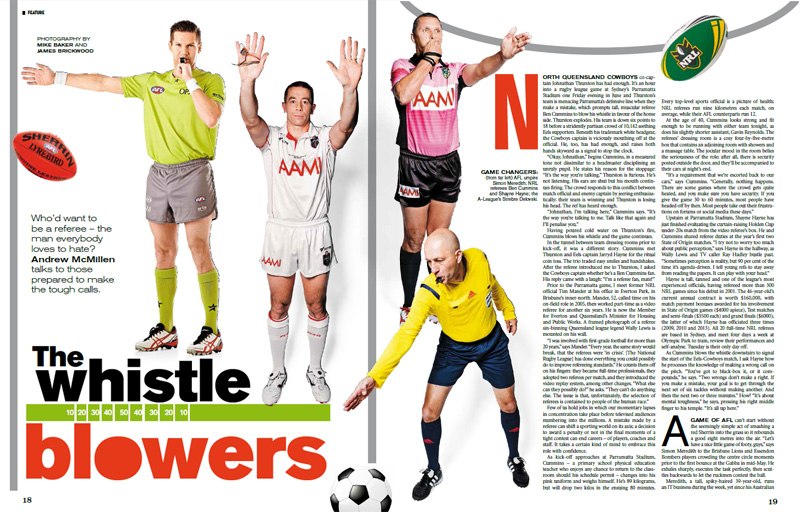

Who’d want to be a referee – the man everybody loves to hate? Andrew McMillen talks to those prepared to make the tough calls.

++

North Queensland Cowboys co-captain Johnathan Thurston has had enough. It’s an hour into a rugby league game at Sydney’s Parramatta Stadium one Friday evening in June and Thurston’s team is menacing Parramatta’s defensive line when they make a mistake, which prompts tall, muscular referee Ben Cummins to blow his whistle in favour of the home side. Thurston explodes. His team is down six points to 18 before a stridently partisan crowd of 10,142 seething Eels supporters. Beneath his trademark white headgear, the Cowboys captain is viciously mouthing off at the official. He, too, has had enough, and raises both hands skyward as a signal to stop the clock.

“Okay, Johnathan,” begins Cummins, in a measured tone not dissimilar to a headmaster disciplining an unruly pupil. He states his reason for the stoppage: “It’s the way you’re talking.” Thurston is furious. He’s not listening. His ears are shut but his mouth continues firing. The crowd responds to this conflict between match official and enemy captain by jeering enthusiastically; their team is winning and Thurston is losing his head. The ref has heard enough.

“Johnathan, I’m talking here,” Cummins says. “It’s the way you’re talking to me. Talk like that again and I’ll penalise you.” Having poured cold water on Thurston’s fire, Cummins blows his whistle and the game continues.

In the tunnel between team dressing rooms prior to kick-off, it was a different story. Cummins met Thurston and Eels captain Jarryd Hayne for the ritual coin toss. The trio traded easy smiles and handshakes. After the referee introduced me to Thurston, I asked the Cowboys captain whether he’s a Ben Cummins fan. His reply came with a laugh: “I’m a referee fan, mate!”

Prior to the Parramatta game, I meet former NRL official Tim Mander at his office in Everton Park, in Brisbane’s inner-north. Mander, 52, called time on his on-field role in 2005, then worked part-time as a video referee for another six years. He is now the Member for Everton and Queensland’s Minister for Housing and Public Works. A framed photograph of a referee sin-binning Queensland league legend Wally Lewis is mounted on his wall.

“I was involved with first-grade football for more than 20 years,” says Mander. “Every year, the same story would break, that the referees were ‘in crisis’. [The National Rugby League] has done everything you could possibly do to improve refereeing standards.” He counts them off on his fingers: they became full-time professionals, they adopted two referees per match, and they introduced the video replay system, among other changes. “What else can they possibly do?” he asks. “They can’t do anything else. The issue is that, unfortunately, the selection of referees is contained to people of the human race.”

Few of us hold jobs in which our momentary lapses in concentration take place before televised audiences numbering into the millions. A mistake made by a referee can shift a sporting world on its axis; a decision to award a penalty or not in the final moments of a tight contest can end careers – of players, coaches and staff. It takes a certain kind of mind to embrace this role with confidence.

As kick-off approaches at Parramatta Stadium, Cummins – a primary school physical education teacher who enjoys any chance to return to the classroom should his schedule permit – changes into his pink uniform and weighs himself. He’s 89 kilograms, but will drop two kilos in the ensuing 80 minutes. Every top-level sports official is a picture of health; NRL referees run nine kilometres each match, on average, while their AFL counterparts run 12.

At the age of 40, Cummins looks strong and fit enough to be running with either team tonight, as does his slightly shorter assistant, Gavin Reynolds. The referees’ dressing room is a cosy four-by-five-metre box that contains an adjoining room with showers and a massage table. The jocular mood in the room belies the seriousness of the role; after all, there is security posted outside the door, and they’ll be accompanied to their cars at night’s end.

“It’s a requirement that we’re escorted back to our cars,” says Cummins. “Generally, nothing happens. There are some games where the crowd gets quite heated, and you make sure you have security. If you give the game 30 to 60 minutes, most people have headed off by then. Most people take out their frustrations on forums or social media these days.”

To read the full story, visit the Sydney Morning Herald.