Streaming concert video hub Moshcam is a super awesome resource for viewing professionally-recorded footage of bands that tour Sydney, Australia. They’ve been an intriguing player on the web music scene since 2007, yet I hadn’t seen their story told anywhere else. I was stoked when co-founder Paul Hannigan agreed to my snooping questions in early April 2009. Here ’tis: the most complete Moshcam interview, ever. Take that, internet!

Streaming concert video hub Moshcam is a super awesome resource for viewing professionally-recorded footage of bands that tour Sydney, Australia. They’ve been an intriguing player on the web music scene since 2007, yet I hadn’t seen their story told anywhere else. I was stoked when co-founder Paul Hannigan agreed to my snooping questions in early April 2009. Here ’tis: the most complete Moshcam interview, ever. Take that, internet!

Hey Paul! I’ve researched you and your company as well as the internet allowed me. Can you describe how the idea behind Moshcam began, and how you decided to undertake the project with your two fellow founders?

I’d returned from Los Angeles where I’d been working with a couple of successful start-ups (Citysearch, and GoTo.com, which subsequently became Overture/Yahoo Search Marketing) and had been helping manage and promote a few bands over there. Living back in Sydney at the time, around 2006, I wanted to do “something with music online”, which was about as specific as my thinking was at that point.

As a fan, I found myself at shows at venues like The Metro and Enmore 3-4 times a week. As it happened, John Reddin, who was a friend and Head of Production at XYZ’s Lifestyle Channel, had worked on a number of television productions with Elia Eliades’ (the owner of Century Venues) production company. Elia had spoken to John about his desire to explore new territory with his venues online and John said “I know this fellow you should talk to”, and arranged an introduction. Through that meeting, the idea of Moshcam was born.

Did you have any experience within the music industry, or were those connections gained through John and Elia?

I’d been a drummer and a music journalist in Europe, and had some band management and production experience there and in the States. But I hadn’t been part of the industry itself in Australia, other than in a reporting capacity as Editor-in-Chief of what was initially Fairfax‘s Citysearch.

Of course, as a tragic consumer, I’d just spent 3 months digitising some 6,000 albums in my collection, so if nothing else, it felt like I was propping up the industry! And suddenly, here was an opportunity to bring a love of music together with a background in content production and technology development?

Moshcam doesn’t seem like the kind of business that’s built overnight. How long did it take to put concept into practice? I understand that you consulted with Melbourne web developers Hyro to build a custom CMS with sharing/playlist functionalities; had they undertaken any similar projects, or was this an all-new interface?

We spent 8 months developing a proprietary back-end solution for Moshcam. To a large extent, I knew what I wanted the site to be in terms of user experience and functionality, so interface design and architecture was relatively straightforward.

The CMS was more of an iterative process in that we were really pushing into new territory around video serving and how to manage those assets.

The Hyro project profile states that you required banner advertising intergration for revenue purposes, yet at the time of writing, I can’t see any ads on the site. When do you plan to include these, and is this the only revenue avenue down which Moshcam is treading?

As a start-up that needed to build significant traffic from scratch, we always wanted to get the product right for music fans in terms of usability, first and foremost, before we thought about how to include things like sponsorship and advertising. Moshcam was always going to be a free offering, so naturally a free-to-air advertising model was going to be a part, but by no means all, of our model at some stage.

However, I think it’s fair to say we are at an interesting juncture in the online world when it comes to music specifically, and there are a host of revenue models which may or may not play out in the months and years ahead.

Moshcam’s stated aim is to make quality live recordings available to be streamed over the web for free. I can’t imagine that every artist you approach is accepting of this goal; what is Moshcam’s strike rate, and have you found that artists have become more welcoming of the idea since Moshcam started in 2007?

Almost every artist we speak to directly loves the idea and only cares about getting their work out there.

With record companies and managers, however, who are often the gatekeepers of approval for us, there’s still a great divide between those that embrace their artists’ music online and those who are more resistant.

It’s easy to understand their concerns since they’ve seen revenues consistently eroded through free downloading but with something like Moshcam, increasingly they see it as a valuable showcase for the artist, both in terms of their existing and potential fanbase, as well as being able to show promoters who may not be familiar with their work just how well they can deliver live.

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was Gary Numan at The Enmore Theatre.

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was Gary Numan at The Enmore Theatre.

Moshcam is only licensed to broadcast each recording over the internet, so the shows currently aren’t available for download. In the coming years, do you think that labels will begin to request the ability to download recordings on behalf of the artists, perhaps at a per-song or per-show cost? This makes a lot of sense to me: stream the show for free, and include the option to buy a high-quality recording – via file download or on a physical DVD – for around the cost of an album.

Absolutely. This is something we are working with the labels to put into effect. As record labels look for new revenue streams, this is one that previously did not exist. The revenue from a gig ends the minute the merch stand shuts up shop. What better way to extend the life cycle of that show than through making it available for fans to buy?

As the aggregator of all this great footage, we are perfectly placed to offer just such a service. As you can imagine, there are a number of issues that need to be resolved in terms of licensing and technology, but we are very hopeful that this will be finalised soon.

Do you present each artist with the same contract? Do some artists try to negotiate so that Moshcam’s recordings can be downloaded?

We have a standard contract that varies only in the length of broadcast terms, from two years to ‘in perpetuity’.

The download issue is not one that really comes up in the negotiations, other than the aforementioned assurances that we don’t offer it for free.

Until we are able to put in place a site-wide download service, we link through to any band who makes their gig available for download or purchase elsewhere.. of which there are very few.

Moshcam is now working in partnership with several Sydney venues. Are you planning to transfer the concept to other cities and venues across the country?

We have built-in studios at The Metro and Annandale Hotel. We also have two mobile units and have filmed gigs at The Forum, The Gaelic Club, The Manning Bar, The Vanguard, The City Recital Hall, and the Hyde Park Barracks (for the Sydney Festival). As a result we have great relationships with those venues so whenever a band I’d like to see on Moshcam is in town, we can shoot at any venue with very smooth integration into their house operations.

We have built-in studios at The Metro and Annandale Hotel. We also have two mobile units and have filmed gigs at The Forum, The Gaelic Club, The Manning Bar, The Vanguard, The City Recital Hall, and the Hyde Park Barracks (for the Sydney Festival). As a result we have great relationships with those venues so whenever a band I’d like to see on Moshcam is in town, we can shoot at any venue with very smooth integration into their house operations.

Other than being able to drill down to a very local level, there are no real economies of scale for us setting up in other Australian cities, since almost every band from another city we’d like to film tours and plays Sydney at some point.

Internationally, I’d love to work with venues in Tokyo, London or Dublin, and New York or LA and cover the four corners of the rock and roll globe! Once we prove the model, I hope there will be opportunities to do just that.

There was some controversy in Brisbane last year when Birds Of Tokyo‘s management kicked up a fuss over bootleg footage of new material that was recorded at The Zoo – coverage here and here. As a music fan, not a business owner, how do you feel about fans recording gig footage and uploading it to video streaming sites? I know that the quality can range from cameraphone-poor to semi-professional setups, yet I feel that there’s an inherent innocence in making an effort to record musicians’ work to share with other fans.

It’s a dilemma isn’t it? As a music fan I want to see and hear anything and everything by the bands I love, but I respect the right of an artist to control their own output, particularly when it comes to quality – which, let’s face it, is the defining point of difference between Moshcam and 30 seconds of mobile phone footage on YouTube.

Obviously the internet has moved the practice of taping shows into a whole new digital distribution environment. But personally, I can’t see how this does anything but increase artist exposure, and ultimately, sales. I do think there is often a lot of disingenuous talk about downloads not affecting sales, depending on who’s making what point, but when it comes to live fan recordings I really do think that is the case.

How do you prefer to listen to music? How has this changed since you bought your first album?

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

I was a bit of a vinyl junkie originally and took a while to make to change to CDs since it seemed a real degradation of the album for the sake of convenience. Tiny artwork, illegible lyrics, reduced dynamics, etc. I think that’s why I embraced the digital format so quickly, as I’d already done my grieving for the original artifact. Now, there’s just the music, and nothing else to get obsessive about.

How do I listen to music differently now than back in the day? I’m a compulsive curator, so it’s almost always a playlist as opposed to an album.

More people are listening to more music than ever before, yet the major labels are resistant to changes in consumer habits due to an effort to retain pre-internet revenue models. Agree or disagree?

Well it’s a prima facie argument, isn’t it? There’s a lot of nonsense spoken on both sides about the effects of digital downloads on the industry. Most kids I know have never paid for music in their lives. That’s just the world they grew up in, it’s not a new digital frontier for them, nor is it a moral issue. They have larger music libraries at 16 than I had after years of buying music as a fan.

But the point is, they would never have bought that music anyway. So it’s simplistic and misleading for the labels to say that this is somehow lost revenue.

What’s more, these kids are incredibly indiscriminate about what they download, which exposes them to artists they would never have heard if they were buying one album a month with their pocket money. This gets them out to live shows; gets them buying merch, and gets them involved in online fan communities, often interacting with the artists themselves. All of which creates lifelong fans who will buy music in some form or other when a pricing model becomes both standardised and sensible.

Likewise, a lot of people who buy music continue to do so, while downloading a lot of free stuff they wouldn’t normally buy to check it out – again, no lost revenue and wider artist exposure boosting live music attendance. Can it really be coincidence that we’ve seen an explosion in live music attendance since since the advent of peer-to-peer download networks?

And then there is the percentage of people who are downloading for free the music that they would have historically paid for. That’s something you can’t refute. Human nature being what it is, and music costing what it does, means that a lot of people are saving themselves money at the expense of the label and the artist. And that’s a problem, especially for the artist. If a musician can’t make a living from their output, how can they survive to make more music?

That’s why the tour has become an income staple. It’s like a return to the strolling minstrel – bands as bards, singing for their supper!

Let’s hope we see some innovation from the labels around pricing to get fans paying for music at a price that’s realistic, in the new digital economy. Whether that’s a tiered licensing model – which would save fans like me who still buy their music a small fortune – remains to be seen, but if you look at media sectors where this has been operational, such as subscription TV, you can see how it could be work for the online music industry.

None of this is being held back by mechanics or technology. It’s all about pricing. However, I think there will always be a demand for a fan to buy an album or a song directly to own it, either as a digital file, or as something you can hold and look at.

What excites you about the music and web industries?

The immediacy. It’s like the fourth wall has been demolished. Although with that comes a loss of some of the mystique for fans and means there will probably never be any more rock gods, I think it’s really healthy.

The internet is basically punk technology for music distribution. Now not only can anyone pick up a guitar, form a band and record some songs, they can get it out there on a scale that has never been possible before.

And in the area of live music, I’m obviously thrilled that we can now capture a gig and share it with fans without having to get into the business of DVD production and distribution. As a fan, this is all part of what I love about being able to experience music outside of the established release schedule of a band’s label.

Before the web, all you heard from a band was what the label released. Perhaps an album every couple of years; maybe a live album or a DVD. Now there are all these great auxiliary moments where you get to see and hear an artist outside the studio, being captured and shared in all sorts of environments.

Moshcam was nominated for a Webby Award last month in the ‘Best Music Site’ category, although you were beaten in the end by NPR. Congrats! Was this a goal of yours, or a total surprise?

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.

To be honest it was a total surprise. Obviously, we’d entered but we haven’t been doing this for too long and we figured we were probably still off the radar of the Stateside luminaries who decide these things.

What are your plans to navigate the ‘interesting juncture’ in online advertising models, and what can we expect from Moshcam throughout 2009?

One thing to understand is that we didn’t start this as a marketing model upon which to hang a product. It was a genuine project by three fans to build something compelling for other fans. That said, it’s far from inexpensive to maintain and obviously we have to find a way to pay for it.

How will we do that? Well, one thing Moshcam enjoys is a startling level of engagement with it’s users. Fans are watching for an average of 31 minutes per show, which is almost 10 times the average for a website visit. And when you realise that video advertising is the fastest growing sector, it’s not hard to see a model there that could work well for us as the market matures.

As discussed, we’re also very keen to work with bands and labels to facilitate a download service, should they wish to sell their shows. We’re also working on some neat licensing and distribution partnerships, and we have a 13-part TV show featuring signed and unsigned Australian bands running on cable at the moment called “Moshcam: Live and Kicking”. We’re not in the business of re-inventing the internet’s business models; we just want to be in a position to offer a valuable service to bands, valuable content to fans and be able to work with whichever models shake out as viable for us.

As for the rest of 2009, you can expect hundreds more great gigs filmed, as well as a lot of new types of content, from backstage interviews to artist-curated playlists. You’ll also see Moshcam on the road around Australia capturing the best local bands in each capital city, and a couple of other cool initiatives we’re developing that will focus on getting some unsigned bands we love much wider exposure!

As you can see, Moshcam is kind of a big deal. Unless I’m mistaken, their streaming concert concept is sailing uncharted waters on the national level, so to speak, and they’re probably a trend-setter on the international front, too. Remember, you read it here first! All 2,900 words! Congrats. To reward yourself, head to Moshcam and watch a show. They’ve got over 500 available, so if you can’t find one that you like, you’re not a music fan. Get the hell off my blog!

Thanks Paul! He can be contacted via email.

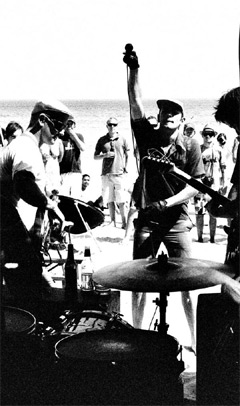

Brisbane natives Drawn From Bees [pictured right] are riding a healthy buzz following their recent national tour and more than a few nods of approval from Triple J. The art-rock four-piece have self-imposed an interesting alternative release strategy: a new record every six months. Explains bassist Stew Riddle: “Over a few drinks after our first rehearsal last year, we decided to use the fact that we’re a band of four songwriters to our advantage, and aim for a prolific introduction to the band. We felt that it would be interesting to break from the new-band cycle of ‘release an EP, tour for 6-12 months, release another EP’, and instead try to put something out every six months.” But the Bees are in a unique situation that encourages frequent releases; Riddle admits: “Dan, our singer, is also a producer, so we can afford to record very cheaply. If we had to hire studio and producer time, it might be a very different story.”

Brisbane natives Drawn From Bees [pictured right] are riding a healthy buzz following their recent national tour and more than a few nods of approval from Triple J. The art-rock four-piece have self-imposed an interesting alternative release strategy: a new record every six months. Explains bassist Stew Riddle: “Over a few drinks after our first rehearsal last year, we decided to use the fact that we’re a band of four songwriters to our advantage, and aim for a prolific introduction to the band. We felt that it would be interesting to break from the new-band cycle of ‘release an EP, tour for 6-12 months, release another EP’, and instead try to put something out every six months.” But the Bees are in a unique situation that encourages frequent releases; Riddle admits: “Dan, our singer, is also a producer, so we can afford to record very cheaply. If we had to hire studio and producer time, it might be a very different story.”

Brisbane’s

Brisbane’s  “I’m still a huge fan of putting on an album and listening to it all the way through. It’s very rare to experience an album that you can listen to from start to finish, and not get bored. It’s very rare to experience that, and it’s one of the things you look forward to in life, as a music fan – that next band that you’ll become completely obsessed with.” When questioned about the free MP3 downloads offered on the band’s Last.FM profile, Donaldson continues: “It’s still good for people to be able to download a song in reasonable quality, just in case they are thinking about downloading the full album. Because we’ve basically arrived at the situation where you can download a song for free, get a feel for the quality of it, and then decide whether you want to waste your bandwidth on it!”

“I’m still a huge fan of putting on an album and listening to it all the way through. It’s very rare to experience an album that you can listen to from start to finish, and not get bored. It’s very rare to experience that, and it’s one of the things you look forward to in life, as a music fan – that next band that you’ll become completely obsessed with.” When questioned about the free MP3 downloads offered on the band’s Last.FM profile, Donaldson continues: “It’s still good for people to be able to download a song in reasonable quality, just in case they are thinking about downloading the full album. Because we’ve basically arrived at the situation where you can download a song for free, get a feel for the quality of it, and then decide whether you want to waste your bandwidth on it!” It’s a valid comment, given that hip-hop song structures are perhaps more reliant on narrative than their rock counterparts. When asked about digital distribution’s effect on the album format, Levinson concedes: “It’s slowly changing people’s attitudes and expectations toward consumption of music. We’re in a transition period where albums retain a huge significance – but some signs suggest it’s disappearing. Stranger things have happened and trends don’t always result in their predicted outcome, though.”

It’s a valid comment, given that hip-hop song structures are perhaps more reliant on narrative than their rock counterparts. When asked about digital distribution’s effect on the album format, Levinson concedes: “It’s slowly changing people’s attitudes and expectations toward consumption of music. We’re in a transition period where albums retain a huge significance – but some signs suggest it’s disappearing. Stranger things have happened and trends don’t always result in their predicted outcome, though.” Regardless, Jackson’s enormous sales in the US simply couldn’t have eventuated ten years ago. Record stores inventories would’ve been exhausted across the country, and compact disc factories would’ve rushed to press more discs to meet the demand. Both of these outcomes still eventuated, but instead of experiencing weeks-long delays, music consumers have the option of instant online gratification: his 2.3 million download count resulted in six Jackson tracks appearing in the Billboard top ten.

Regardless, Jackson’s enormous sales in the US simply couldn’t have eventuated ten years ago. Record stores inventories would’ve been exhausted across the country, and compact disc factories would’ve rushed to press more discs to meet the demand. Both of these outcomes still eventuated, but instead of experiencing weeks-long delays, music consumers have the option of instant online gratification: his 2.3 million download count resulted in six Jackson tracks appearing in the Billboard top ten. At a national level, ARIA’s

At a national level, ARIA’s  To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first.

To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first. That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s.

That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s. In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept.

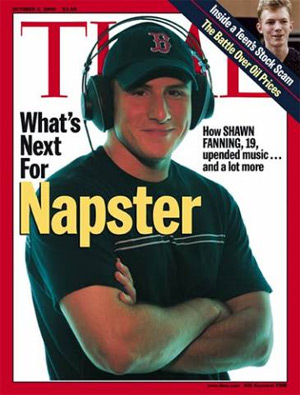

In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept. Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0.

Or if you were really cluey, you’d use an online software application called Napster to find a fan who’d encoded the CD into the MP3 format. You’d download the CD from them for $0. Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side.

Up until the release of the LP, musicians had accepted that – owing to the limitations of the 78 RPM format – they could only record songs that were shorter than four minutes in duration. Double-sided releases were common, which resulted in the distinction between the A-side – the featured song that was most desirable for radio play – and an additional song, known as the B-side. As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores.

As a musician ten years ago, commercial success was largely dependent on signing a huge chunk of your profit away to a corporate entity who had the cash with which to line the pockets of the corporations that controlled the interdependent businesses of radio, music television, touring and record stores. This is my first interview on behalf of

This is my first interview on behalf of

I’m not sure if it’s the industry that’s pushing artists to releasing albums, or whether it’s more the artists holding on to the idea. Certainly, if you take

I’m not sure if it’s the industry that’s pushing artists to releasing albums, or whether it’s more the artists holding on to the idea. Certainly, if you take

Streaming concert video hub

Streaming concert video hub

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.

When do you expect the RPM album to be in stores?

When do you expect the RPM album to be in stores?

Finally – as a musician in 2009, what’s the biggest barrier to getting your music heard? How do you overcome that barrier?

Finally – as a musician in 2009, what’s the biggest barrier to getting your music heard? How do you overcome that barrier?