Qweekend story: ‘Beat Generator: Tom Thum’, October 2013

A story for The Courier-Mail’s Qweekend magazine, originally published in the October 26-27 2013 issue. Click the below image to view as a PDF, or read the full story underneath.

Beat Generator

A young Brisbane man with a versatile voicebox has built a career out of the unlikeliest of musical talents.

Story Andrew McMillen / Photography David Kelly

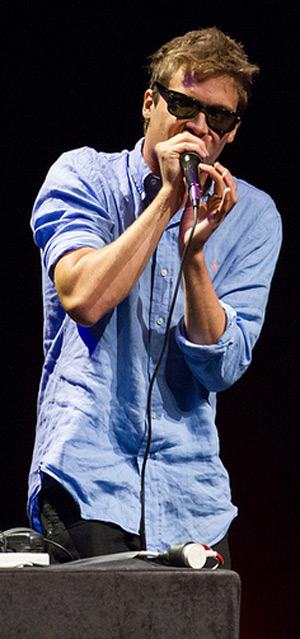

Moments after completing the most important performance of his life, Tom Thum gave a gesture that seemed fitting: he leaped in the air and clicked his heels. The Brisbane-based musician had spent the last eleven minutes with the thousand-strong Sydney Opera House audience in the palm of his hands, entertaining TEDxSydney conference attendees with little more than his voice and a microphone.

“My name is Tom, and I’ve come here to come clean about what I do for money,” he said upon taking the stage in May. “I use my mouth in strange ways in exchange for cash.”

Innuendo aside, Thum’s description of his own talent couldn’t be more apt. Beatboxing — a technique rooted in using the human voice as a percussive instrument in the absence of a boombox or a drum kit — is a highly specialised skill within hip-hop culture, and one that has proven almost impossible to cross over into the mainstream. Yet through a freakish ability to accurately mimic musical instruments and layer intricate compositions, allowing him to replicate the vibe of a smoky jazz dive or Michael Jackson’s signature hits – among many other unlikely and impressive feats – the 28-year-old has connected with a mass audience.

The standing ovation was enough to prompt a celebratory heel-click, but the best was yet to come: in the hours that followed, his vocal talents contributed to an impromptu jam session with guitar virtuosos John Butler and Jeff Lang, and he was approached by Audi Australia representatives to star in an online advertising campaign that saw Thum mimicking the vehicle’s complex array of sound effects. Footage of the performance clocked one million YouTube views within two days of being uploaded in July. By the end of September, Beatbox Brilliance – so dubbed by conference organisers – had surpassed six million hits and become the most-watched TEDx video of all time. The boy from Brisbane christened Tom Theodore Wardell Horn had gone viral.

++

While the empty building bakes in the heat of an early spring day, the artist reclines in a well-worn office chair in a recording studio at Elements Collective, a hip-hop dance studio in inner-north Brisbane’s Fortitude Valley. He tweaks the vocal mix on a local MC’s debut album at high volume while hunched over a Macbook. Navy curtains block out the sunlight; a bold, colourful graffiti mural dominates the back wall. Wearing long pants, a baggy black shirt and silver sneakers, the jetlagged artist is enjoying his second full day back in the Queensland humidity.

Some of Tom Thum’s appeal can be ascribed to his gregarious on-stage nature. In the video, he comes across as a personable extrovert who revels in the ability to share his talent with the middle-aged audience, many of whom have probably never seen or heard anything like it. It helps, too, that the tanned, blue-eyed young man is easy on the eye; plenty of YouTube and Facebook comments mention his appealing appearance. It’ll disappoint those adoring female fans, then, to learn that he’s been in a relationship for three and a half years. “I think she likes my work,” he says thoughtfully. “But she doesn’t like the things my work makes me do.”

By this he refers to the fact that most of his year is spent on the road. The past several months have been devoted to touring throughout the United Kingdom, Europe and United States, performing both solo and as a duo, alongside Melbourne-based singer and guitarist Jamie Macdowell.

While Horn’s dance card has been packed of late – he’s spending a little over a week at home before jetting off once again, this time to work on a hush-hush project with a well-known American animation studio – it’s been a hard slog to get to this point in his career. Born at South Brisbane’s Mater Hospital on April 2, 1985, Horn attended Yeronga State School and, later, Anglican Church Grammar School in East Brisbane. “People always ask me if my real name is Tom Thum,” he says. “My parents aren’t that sadistic! Tom Horn would’ve been a good stage name; either that, or a porn star name.”

Horn is a true student of hip-hop, having embraced the art form in its four distinct elements – aural, physical, visual and oral – and excelled at each of them. His entrée into Brisbane’s underground hip-hop community began with taking an interest in graffiti writing in 1999. He started learning how to breakdance in 2000, but it wasn’t until 2001 that Horn heard beatboxing for the first time. “It was a couple of years after that until I realised it was something I could pursue,” he says. “I just really liked it, and worked at it. I never thought about it competitively; I did it because I was a hyperactive kid with too much time on his hands.” He was never diagnosed with attention-deficit or any associated disorders. “I just picked up a microphone,” he shrugs. “That was the medication.”

After graduating from Churchie and exploring the fringes of Brisbane’s independent music scene, Horn started a Bachelor of Arts (Psychology) at southside Griffith University in 2003. He sat in a crime and justice lecture and wondered, “What am I doing here? I’m a hyperactive little graffiti writer in a room full of aspiring cops! The second that I understood that no-one was going to force me to go to uni, I was like peace, baby!”

Horn gave up breakdancing earlier this year as a result of constant injuries and between 2007 and 2012 toured the world with Tom Tom Crew, a theatre troupe that featured five acrobats backed by three musicians who blasted loud drum’n’bass, dub and hip-hop. Horn has also released three albums as a rapper under the MC name Tommy Illfigga, an EP as Tom Thum in 2012, as well as a 2010 LP of beats as Crate Creeps, a partnership with fellow Brisbane musician DJ Butcher. Beatboxing is Horn’s forte, though: his versatile voicebox won him first place at the World Beatbox Battles alongside compatriot Joel Turner in 2005; and in 2010, he was awarded “best noise and sound effects” at the World Beatbox Convention in Berlin.

++

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

One Saturday morning last November, Horn woke with a start in his rented Berlin apartment. His musical offsider, Jamie Macdowell, was about to leave to get a second key cut. The pair had performed together the previous night and come home, completely sober; a strangely quiet Friday for two young men in a foreign country. Suddenly, Horn broke the silence by yelling for his friend. “I went into his bedroom and Tom was reeling,” says Macdowell, 27. “He said it felt like there was a ten cent piece on his sternum, and an elephant was sitting on the coin. As soon as he sat up, he just lost his mind. The pain got so intense that he couldn’t talk or move. He fell back down onto the bed and was shaking. It looked like he couldn’t breathe.”

An ambulance took him to hospital, where he was admitted to a cardiac ward. His roommates were two elderly Germans. The pair listened to the doctor describe what had happened to Horn in complicated medical terms. “We couldn’t understand; we were nodding quizzically,” says Macdowell. “Tom got it before I did. He said to her, ‘is this the kind of thing that you would explain to someone who’d just had a heart attack?’ She looked straight at him, full of intent, and said ‘yes’.” The next day, Horn underwent an operation to put a stent in his heart; “a rollcage that stops your artery from collapsing,” in his words.

That near-death experience provided fertile ground for planting the seeds of artistic inspiration. “It was fucking boring in the hospital,” Horn says. Naturally, his creative mind wandered. While he couldn’t understand what the doctors or his roommates were saying, he was intrigued by the beeps, hums and whirs of the medical machinery that kept him alive. A key moment in Horn’s solo show is a layered reimagining of the sounds of the hospital, which gradually evolves into an evocative cover of Hearts A Mess, a 2006 single by chart-topping Melbourne musician Gotye, aka Wally De Backer.

To his frustration, the assumption that many strangers make upon hearing this story is that Horn’s heartrate must have been artificially boosted. This couldn’t be further from the truth. “Everyone assumes that, because I’m a musician and I had a heart attack, [I should] lay off the cocaine a bit,” he sighs. “No-one can tell me what [the attack] was from. I’d been deemed perfectly healthy by doctors. It’s not what you expect at age 27. Now I have to live on these medications – but at least I get to live on them. It gave me a great piece for my show … Everyone seems to think that heart attacks only happen to people over 60.”

Macdowell adds: “Tom’s the most sober person I’ve ever met. He’s changed a lot since the heart attack. His consumption of alcohol has almost completely ended. He eats really well, and tries to exercise. It’s really changed him for the better.”

Ever the perfectionist, Horn says he’s got four full albums of original material that haven’t yet seen the light of day due to his “inability to let go of things, and to call something ‘complete’. I’ve got a vault of music that hasn’t been opened yet.” He adopts the voice of a Hollywood mad scientist: “Soon I shall relinquish my pretties!”

With a few more dollars in his pocket of late, he’s keen to outsource some of the do-it-yourself ethic that has always surrounded the production of his own music. “I’ll still have 100 per cent creative input and control,” he says, “but I can be like, ‘okay, press record now! Drop the bass out of this, filter out that sample, boost this’. Because now I know what I’m talking about, I can still drive the ship without having my hands on the wheel.”

++

For those few months each year that he calls Brisbane home, Horn stays with his parents in inner-south Annerley. His 60-year-old mother, Sue, admits that the cloud of noise that surrounds her eldest son can be irritating.

“Especially if you’re watching something really good on TV, one has to be very patient,” she says. “I think if he lived at home all the time, it could be quite difficult. [This living situation] probably works well for us all.” The former nurse and her husband Murray, a forensic scientist, occasionally fret about his chosen career in the performing arts. “I’m not really happy about it, because I think it’s not a terribly stable industry. But he’s his own person. We have no influence,” she laughs. “We frequently have these discussions.” Are they playful discussions, or serious? “Playfully serious,” she replies. “Tom doesn’t appreciate them at all! He went to uni for a year and said that was the greatest waste of time. But I think he does have a lot of talent.”

Macdowell agrees. “Tom is a prodigious noisemaker. He has no attention span for anything except beatboxing and creating sound effects. His practice is relentless. The guy just doesn’t stop making noise. It infuriates me when we’re on tour; I was okay with the European tour ending, just to get some silence,” he laughs. “But every time I think about saying something, or coming close to telling him to shut up, I remind myself that that’s why he’s so brilliant – he doesn’t stop.”

While Qweekend’s photographer and his subject explore the colourful canvases at Elements Collective, 25-year-old Alex Steffan slips into the studio, slides on a pair of headphones and listens to the latest vocal mix that Horn has spent the morning working on. He nods his head in approval. “He was always the most talented one of our group of friends; he always had freakish abilities with his beatboxing, breakdancing and graffiti,” says Steffan, whose stagename is DJ Butcher. “We’ve all been waiting for him to blow up. All of a sudden, the TEDx talk has let the world know what we’ve known for ten years.”

Throughout the photo shoot, Horn’s voicebox produces soulful trumpet tones, intricate beatbox phrases, and even a note-perfect take on Fly Me To The Moon. He’s preoccupied with perfecting his saxophone – “reed instruments are hard; I’ll get there one day” – and says that the hardest thing about making sounds with his mouth is in finding the instruments’ accents; their defining characteristics. The pluck in a blues guitar, or the woozy feel of its tremolo arm. The way the pitch slightly wavers in a trumpet when the player stops blowing so hard. The breathy tone of a flute. These are the sounds that Tom Horn studies and rehearses in a constant feedback loop that fills nearly every waking hour.

“People often ask me if I’m making a living out of beatboxing,” he says. “I reply, well, I’m making a ‘not dying’. I’m not hungry. I’m definitely not making a living in terms of the traditional sense of saving up for a house, a home loan, a wife and kids; an Audi …” he smiles. “I’m not rich monetarily, but I’m definitely rich in experience, and that’s my priority at the moment. I’m not earning mad cheddar, but I’m 100 per cent happy with my life.”

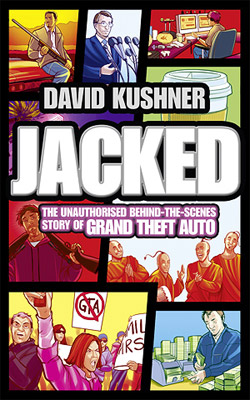

‘GRAND Theft Auto revolutionised an industry, defined one generation, and pissed off another, transforming a medium long thought of as kids’ stuff into something culturally relevant, darkly funny, and wildly free,” David Kushner writes in his second video game-themed book.

‘GRAND Theft Auto revolutionised an industry, defined one generation, and pissed off another, transforming a medium long thought of as kids’ stuff into something culturally relevant, darkly funny, and wildly free,” David Kushner writes in his second video game-themed book.