I went to a screening of ‘RiP: A Remix Manifesto‘ last night, along with around sixty others. The audience included local promoters, distributors, musicians, writers and university students. Via nfb.ca:

I went to a screening of ‘RiP: A Remix Manifesto‘ last night, along with around sixty others. The audience included local promoters, distributors, musicians, writers and university students. Via nfb.ca:

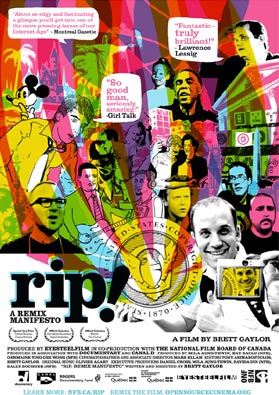

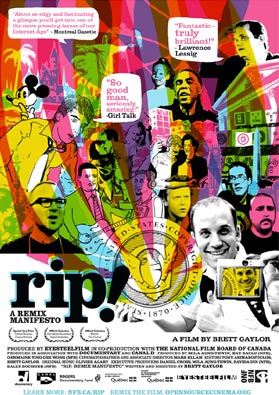

In RiP: A Remix Manifesto, Web activist and filmmaker Brett Gaylor explores issues of copyright in the information age, mashing up the media landscape of the 20th century and shattering the wall between users and producers.i

The film’s central protagonist is Girl Talk, a mash-up musician topping the charts with his sample-based songs. But is Girl Talk a paragon of people power or the Pied Piper of piracy? Creative Commons founder, Lawrence Lessig, Brazil’s Minister of Culture Gilberto Gil and pop culture critic Cory Doctorow are also along for the ride.

A participatory media experiment, from day one, Brett shares his raw footage at opensourcecinema.org, for anyone to remix. This movie-as-mash-up method allows these remixes to become an integral part of the film. With RiP: A remix manifesto, Gaylor and Girl Talk sound an urgent alarm and draw the lines of battle.

Which side of the ideas war are you on?

The screening was organised by Phil Tripp, who started The Australasian Music Directory, as well as themusic.com.au and IMMEDIA!. In addition to the film screening, Tripp organised a panel comprised of five Brisbane music authorities to discuss the film, and some of the wider issues that the modern music industry is facing.

I transcribed the majority of this panel discussion – approximately an hour’s worth – because I want to share their thoughts and opinions with those who weren’t there.

Some of their comments are valid. Some are misguided. Some are ridiculously outdated. I’m not going to point out which is which, though. That’s up to you.

Note that this post is quite long – around 8,000 words. It gets into some very specific topics. I have occasionally edited their words for clarity, and omitted a couple of uninteresting bits. But you should read it to gauge the five speakers’ beliefs about what is happening to the music industry. To save you scrolling up and down, I will repeat each speaker’s title each time they are quoted, so that you can contrast their opinions against their commercial beliefs.

Download links for the audio files are at the bottom of this post. Enjoy.

[Tripp gives an introductory speech before the film starts.]

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA! [pictured right]:

The future of music, the way we look at it, is about going overseas. But not giving up your home country. You hear my American accent; I’ve been here 28 years, and I always love to come home to Sydney. And for the set of trips that I’m doing this month, I found a film at South By South West (SXSW) – which is an event in Austin, Texas that I rep for this region – to show throughout Australia. We decided to show it, not because I’m a benevolent person wanting to educate you, but because I want to give you an idea of where the future of music is going, from one point of view.

The future of music, the way we look at it, is about going overseas. But not giving up your home country. You hear my American accent; I’ve been here 28 years, and I always love to come home to Sydney. And for the set of trips that I’m doing this month, I found a film at South By South West (SXSW) – which is an event in Austin, Texas that I rep for this region – to show throughout Australia. We decided to show it, not because I’m a benevolent person wanting to educate you, but because I want to give you an idea of where the future of music is going, from one point of view.

Now, this film is propaganda. It is a film that has been made with a purpose in mind, and a message. And the message is, that when I was a kid, my teacher told me, along with the rest of the class, that “tonight, we want you to go home to your parents and we want you to cut out little pictures, and things from magazines, and bring them in tomorrow, and we’re gonna take out the paste pots, and we’re gonna glue them all down on paper, and we’re gonna put them out on the wall outside, and we’re gonna make what’s called a collage”.

Little did she know that that was a violation of copyright. Taking other people’s images and mixing them into a ‘mash-up’ of visuals. Back then it didn’t matter. Now, you people have tools that go far beyond scissors and paste pots. You have the tools to take music and turn it into a whole new form of art. And that’s great. Except I’m a commercial bastard. I have intellectual property – the Music Directory, and our site themusic.com.au – and if anybody wants to take my intellectual property, which is basically a phone book, and put it on their website because they’re believe it’s free because it’s on the internet, they will get a hot testy letter from me, with the legal advice that I may take their house, or whatever property they have.

So I’m not exactly the kind of guy who believes that people should take intellectual property and steal it, and use it, and make money from it. The cool thing about this film is that it talks about somebody who has done just that, but he’s done it as art. But there came a point at which it crossed over into commerce. When I found out about this film at SXSW, I thought this would be a great introduction to the conference we’re doing in August…

[Tripp describes his conference.]

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

I think this is the most exciting time for you people to be in the music business, because although the recording industry has gone to shit, the music business is actually doing pretty well. Especially for the live side of music, or new revenue streams though mobile phone companies, or through internet sites, and also through the future of what will evolve.

Anyway, I hope you enjoy the film tonight. I hope it makes you think. I hope you realise that there is the commerce of music, and there is the art of music. And the two don’t necessarily mix. Unless you’re going to make money and also share the money you make with the people that actually created it originally.

[The film plays. Tripp then introduces the panel speakers.]

Paul Paoliello – CEO, Mercury Mobility

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine

Steve Bell – Editor, Time Off

[The panel discussion begins.]

[Tripp describes local initiatives to help Australian artists export their work nationally and overseas.]

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

[…]There’s another group called Sounds Australia, which this year helped Australian artists so that they were able to afford to attend SXSW and The Great Escape [Andrew’s note: Sounds Australia also appears to be run by Tripp.]. And there’s AusTrade, the Australian Trade Commission, which has been one of the greatest evangelists for Australian music from our Government in a long time. The Australia Council [For The Arts] has just this year got on board, after supporting the works of dead composers for many years, and forms of music called ‘opera’, ‘classical’ and ‘symphonic’.

This year, it’s cool to be contemporary. They have put considerable money behind the need to take Australian artists to the world. Because, let’s face it, kids: you’re not gonna ‘make it’ here. You’re not gonna make enough money in this country, at this point, to actually have a living. So you need to have an export strategy.

[The panellists discuss their thoughts and opinions on the film. I didn’t transcribe this bit.]

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Rick, I want you to tell us – because you have a relatively successful band here, out of Brisbane – have you made any money from mobile music? And if so, how?

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People [pictured right]:

As far as music mobile for The Boat People is concerned, it’s been an area which we really haven’t pursued. It’s one of those things that’s on the radar; everybody’s saying that this is the way in which it’s going to take over, and that everyone is going to be consuming music through their mobile phone. We’re well aware of that, but my understanding is that it’s very much a media that’s beginning, and as Paul described, it’s going to be dominated by what’s in the charts. Our music is distributed through Shock, and so Shock is working with different distributors who will likely make our music available on mobile platforms. But our mobile music income at this stage is negligible. And I’m not sure whether it will become relevant for us.

As far as music mobile for The Boat People is concerned, it’s been an area which we really haven’t pursued. It’s one of those things that’s on the radar; everybody’s saying that this is the way in which it’s going to take over, and that everyone is going to be consuming music through their mobile phone. We’re well aware of that, but my understanding is that it’s very much a media that’s beginning, and as Paul described, it’s going to be dominated by what’s in the charts. Our music is distributed through Shock, and so Shock is working with different distributors who will likely make our music available on mobile platforms. But our mobile music income at this stage is negligible. And I’m not sure whether it will become relevant for us.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Okay, what about iTunes?

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

We work as an independent band with IODA, who is an aggregator for digital music. So our music is distributed by them internationally. In Australia, it’s through Shock. In terms of digital sales, our experience is that 80-90% of our digital sales are through iTunes. We’re on Napster and Rhapsody and all the different sites that exist, but iTunes is where the vast majority of sales come through. Digital is fantastic: it means that you’re very mobile, very agile, and it means that the band can be everywhere at once in the world very quickly. But it’s really the same game as it always was: “how do you sell records?” “How you sell digital?” And you need to be able to promote [the product]. Our sales internationally have happened through traditional means; namely, radio. In the US, we’ve had a good run with radio – we’re currently on about 20 stations, so we’ve had a lot of support – and when that happened, our digital sales on iTunes spiked considerably, and they’ve been growing since.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

What about YouTube?

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

This is an area which is very close to my heart, because I think there’s such a great opportunity for bands to have an incredible reach by doing something very inexpensively. The Boat People tried to do something smart, and it didn’t quite work (laughs) We created a film clip for Awkward Orchid Orchard, where within the clip, there are clues for 54 band names, from The Beatles, to The Shins, to The Boat People. So we thought this’d be a fun game for any music nerd, and they’d share it with their friends. And it worked to some degree – we’ve had 20,000 hits, whereas our previous clip had about 5,000 – so it’s kind of worked.

But there’s a Brisbane band called Blame Ringo, who’re pretty unknown. The band had an idea to shoot a film clip, where they got a friend to go to Abbey Road and shoot at the pedestrian crossing, to capture how people mimic The Beatles album cover. They cut a few pieces out of that and created a clip from their three hours of footage, and it put it up on YouTube using a few Beatles keywords, and in a few weeks they got, I think, around half a million hits. They had an interview on Weekend Sunrise, and they got a call from a US national TV show. This is a band that had absolutely nothing going on! This is staggering. YouTube is a fascinating tool, which if people are creative and thinking, they can use to give themselves a real ‘leg up’.

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine [pictured right]:

That’s just making me think; going back to the movie, there was that comment about how the future of music will be less creative, because of the locks that are being put on copyright. But here’s this band, Blame Ringo, who have just shown us that if you’ve got a good idea, and if you can follow it through, and make it happen on a world stage. The technology’s in your hands. You don’t have to grab someone else’s inspiration, and rework that; if you’ve got an idea in your head, then you’ve got the tools to make it happen. So I don’t agree with that comment, that ‘the future will be less creative’. I think that’s wrong.

That’s just making me think; going back to the movie, there was that comment about how the future of music will be less creative, because of the locks that are being put on copyright. But here’s this band, Blame Ringo, who have just shown us that if you’ve got a good idea, and if you can follow it through, and make it happen on a world stage. The technology’s in your hands. You don’t have to grab someone else’s inspiration, and rework that; if you’ve got an idea in your head, then you’ve got the tools to make it happen. So I don’t agree with that comment, that ‘the future will be less creative’. I think that’s wrong.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Rick, how has your band been ripped off digitally? Have you got any stories of how you’ve discovered some copyright infringement?

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

No, but we’re looking forward to when it happens (laughs) Nothing’s really happened like that for us, at this stage. I don’t think we’re quite famous enough to be ripped off at this particular point.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

You don’t have to be famous to be ripped off. You know what happened to me? Our music directory is online, and some people will subscribe to it and then they’ll pull down all the information. And we’ll find it, because we have little bots that search. We get people all the time who take our information and put it up on their website, like they’re creating a new music directory and giving it away for free. Man, I have had so much fun with them. There is a publisher named Deke Miskin who has a big house on the harbour. And Deke had some stupid intern take my information and put it in another magazine. We found it on the newsstand; I called him and said “Deke, guess what? It’s settlement time. Violation of copyright. You are now on notice. Do you want to go to court? Would you like me to shame you in the Sunday papers?” And rather than do that, Deke, being the man of honour that he was, paid me a whole bunch of money to shut the eff up. And then he withdrew the title from circulation. It was one of those little “how to get into the music business” mini-magazines, for suckers, for $6.95.

Now, you’re in the magazine business, Steve. You’re in the new age of finding out that the print medium is being shot to shit, while the internet has everything for free. However, I must say that I do a lot of work with Street Press Australia; they’re one of our conference sponsors. What I find interesting is when Leigh Treweek [of Street Press Australia] spoke for this event in Perth and Melbourne, he talked about the whole idea of branding, and how his publications and street press in general is not going away anytime soon. He also gave some very interesting stories of how bands become brands. How do you see the internet affecting you, as a street press publication, and what are some of the more innovative ways that musicians can use your medium to push themselves ahead?

Steve Bell – Editor, Time Off [pictured right]:

Well, there’s no doubt that the dissemination of information is definitely changing. We’d be fools to not realise that. We haven’t rushed into a web presence. I mean, we’ve got websites and stuff, but they’re just sort of token for the moment. We’re trying to work out the best model for going forward, and what it’s going to entail. We’ve spoken to a lot of people, we’ve actually hooked up some meetings with Craig Treweek, Leigh’s brother, this week in Sydney with some friends of mine who’ve got some really interesting ideas on the future of the web. It’s moving so fast; it’s very difficult to really work out. There’s no black or white.

Well, there’s no doubt that the dissemination of information is definitely changing. We’d be fools to not realise that. We haven’t rushed into a web presence. I mean, we’ve got websites and stuff, but they’re just sort of token for the moment. We’re trying to work out the best model for going forward, and what it’s going to entail. We’ve spoken to a lot of people, we’ve actually hooked up some meetings with Craig Treweek, Leigh’s brother, this week in Sydney with some friends of mine who’ve got some really interesting ideas on the future of the web. It’s moving so fast; it’s very difficult to really work out. There’s no black or white.

So we are very aware of it, but we’re sort of playing it by ear, because there’s no certainty as to the future. But we do realise that all the interviews Time Off has done are a resource. And by just letting them go each week, and not accumulating them into some kind of archive, we are, down the track, burning ourselves. We should be putting this together and using it as the resource that it is. At the moment we’re not; it’s just going into the paper each week, and becoming landfill, or whatever happens to it. We are addressing it, but it’s still in the infancy stages, I guess you’d say! (laughs)

In terms of bands using us, probably the first thing that comes to mind is Savage Garden meeting through our classifieds, so there’s still that old sort of model. Don’t blame us for that! But the street press is just a different form of exposure. It’s one of many that you use. I can’t think of any real examples.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

What about brands using street press to push themselves forward to another level, like Chupa-Chups, for example, going onto MySpace? What sort of brands have done anything innovative with you in the last year that you can think of, and use as an example?

Steve Bell – Editor, Time Off:

Because it didn’t work very well, I can’t think of the company, but there was a media company that put a DVD on the front of an issue, who paid quite a bit of money to.. you know, often there’s things like that. Companies will use us as a way of disseminating their product, or samples, just because of our distribution channels. But that’s not really using our brand as such, it’s more using our pickup at various locations. Do you have anything in mind? I’m struggling to think of anything.

[Tripp describes one of his magazines, Urban Animal, to the audience.]

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Lars, where do you see the future of the music industry here in Australia, and overseas?

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine:

Well, it’s the million dollar question, isn’t it? As a kind of segue to what you were just saying about the pet industry, and how “you can’t download dog food”; the one really, really strong point of the music industry in the last couple of years has been the live business. The reason why the live business is so hot is because people love to see bands, and you can’t steal a live performance. Unless you dig a hole under the fence at a concert, you can’t actually rip it off. So live performance has been booming. It’s absolutely been soaring in recent years. The future of the record industry, now, we are seeing the major record labels trying their hand at getting into the live business, because they realise, “hey, we’re kind of screwed here”. Revenues in the last ten years have dropped a lot, so to safeguard their future, the big labels are looking at investing in companies involved in live music. Or going out alone.

In a way it’s desperate, because the record companies don’t have expertise in the live music business. There’s a lot of ‘shyster’-ing that goes on in the live business, and the record labels don’t really know this. They don’t know that sector of business so well. We’re going to see a lot of jostling in that space over the next couple of years.

Sony Music are the first of the four Australian majors that have declared their attention to have a go; they’ve created a touring division. They’re co-promoting Simon & Garfunkel. Huge tour; there’ll be a lot of money on the table. If tickets don’t sell out for this, I’m sure that Sony Music will lose a lot of money. They will get their fingers burned, because it’s a tough business and they’re playing with some real sharks. Those Simon & Garfunkel world tour dates have only been announced in Australia so far, so the world will be watching here first.

To date, the tickets haven’t sold out. We’re in tough economic times. No-one really knows if they want to see Simon & Garfunkel, either, or whether they can still ‘cut it’. It’s really interesting. From a journalist’s point of view, I’m interested to see how this goes, because for me, that is the obvious route that record companies will take – entering the live business – because live is hot.

Digital.. everyone’s been talking about digital for ten years. Of course, we saw how the RIAA clamped down stupidly on Americans, in particular, but the international recording industry have done the same thing in issuing lawsuits against downloaders. It was a bone-headed thing to do, but they were desperate to get a handle on control of the dissemination of music. Now, the record labels are so far behind the game, they have to catch up. They’re also getting into bed with technology firms, and they have to. They have to get wise to the digital environment, because that certainly is the way forward.

We’re not there yet. Digital music in Australia accounts for, I think, about fifteen percent of album sales, so it’s really ‘small beer’. Those headlines you read about “CDs are finished, it’s all about digital” – that’s not right. We’re still looking at 85% of record sales in Australia comprising CDs; although it’ll ebb away in time, we don’t know when. In a nutshell – and I’ve rambled on – the future is certainly going to be a strong live business. We don’t know if it’s peaked yet, and I suppose that it hasn’t. And digital will be the way forward, but it’s not here yet. But the record labels have a lot to learn.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Two comments. Gregg Donovan, who is the manager of Airbourne, Josh Pyke, Grinspoon and a few other bands, talked at our seminar in Sydney about how he had been approached by major multinational record companies who wanted to do ‘360 deals‘ with some of his artists. For those of you who don’t know what that is, a 360 deal is where a record company wants to act as the manager, the touring promoter, the agent, the merchandiser, the publisher; essentially, everything.

And Gregg went to them and say, “okay, I’ll tell you what”, to this American record company. “Let me see your t-shirts. Where are your t-shirts? You manufacture t-shirts? You’re a merchandising company? Take me to your t-shirt factory.” And of course, they couldn’t, so he said “no deal there”. And then he asked, “you have management? You have a management company within the label?” And they replied, “oh, no, but we’re getting it…” Gregg said, “no”. What happened here was Sony, aside from setting up a touring division, they also bought half of that doofus from Australian Idol, Paul Caplice [Andrew’s note: I can’t find this name online. Maybe I can’t spell it.] and David Champion, who I call “tweedle-dumb” and “tweedle-dumber”. They bought into this, and they found out that it’s a very expensive job that you have ahead of you, if you have incompetence running the management side of a record company. It’s actually very funny to watch from the outside.

And I’ll make one more comment on what you said, Lars. Yes, digital is only fifteen, maybe twenty percent of revenue in our industry, but every download sale is a sale without physical product. Most albums print out a thousand for every hundred they sell. And it takes about ten or twelve failures for one success. So although physical product is selling more, it’s also destroying more. It’s being given away, it’s been put into landfill et cetera, because you can only buy it in a record store eight hours a day. With digital, you can buy it 24/7. Steve, tell us, where do you think it’s going?

Steve Bell – Editor, Time Off:

I guess it ties in with what you were saying about 360 deals. For the last ten or so years, most bands have changed the way they’ve approached revenue streams. I used to run TSP, the t-shirt printers, [who are] one of the biggest merch companies in Australia. We used to represent big overseas touring bands – Green Day, Foo Fighters, Chili Peppers, Nine Inch Nails, Tool, what have you. The amount of money that we’d make out of any given show out at Boondall (Brisbane’s Entertainment Centre), and I’d see the figures for the whole Australian tours, while knowing the costs of this stuff, it was quite remarkable. There was a fad of punk kids wanting to buy those fuzzy wristbands, which were selling for around $15 at shows, and I think if you make them in bulk they cost around 8 cents per unit.

So bands who are focussing on touring, and merchandising, and the different revenues that come with that are changing their approach to recorded music. Instead of being a cash cow itself, it’s become a way of drawing attention to the band and their different revenue streams. I mean, they still want to make money from it, of course. But I think the one certainty is that there’s always going to be a market for music. People still want to create, and there’s obviously all of us here tonight as music fans. It’s just going to be a matter of how it’s disseminated, and how it’s received. I think it’s exciting, really, that all these new models are out there, and bands are discovering that they don’t need to spend so much money to make great music. I still interview a lot of bands, though, and more often than not, they’re not spending five months in a studio, they’re doing the bulk of it at home. Costs are going down, and there’s going to be a lot of changes down the track, but I think it’s a really exciting time. Music’s going to flourish, despite what the nay-sayers say.

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

The future of music.. I don’t know, of course. But as a manager trying to help artists to flourish and survive in their careers, it’s quite true that the recording income from CD and digital sales are one or two income streams, but there’s maybe 15 or 20 income streams that flow from the recording. So how you look at it commercially is an interesting question. There is no need to despair in that sense: it’s always been tough, it’s still tough and it will be tough to make a sustainable career as an artist, but the fact that there’s a decrease in recording income shouldn’t be such a big problem.

One of the opportunities which is here now is, because of the internet, and MySpace, and Facebook et cetera, is the ability to create communities around your band. And this suits some bands better than others, but I think it’s worth thinking about. A great example is a Brisbane band called The Red Paintings, who I’m sure you all know. One of the strong things about the band, outside of the music, is that Trash, the band leader, has a very defined, strong philosophy of what the entire act is about. And I think that’s very interesting. He understands it so well that when he talks to you, you’ll get it when speaking with him for two minutes. I spoke to him briefly on a telephone call and he explained to me that, with his live shows, the philosophy is that it’s about being able to express yourself creatively and freely, without hurting anybody. So that’s the essence behind his whole live show. When you go to a Red Paintings show, you’re allowed to paint, and have a lot of fun, and do things that you’re not allowed to do normally, but you can do it at a Red Paintings show.

Now, with that, he’s actually developed a community of people that subscribe to more than just the music. They subscribe to this philosophy that he’s espousing. I don’t know if you know this, but for his last record, he put out to his fans that if they put in $40, they’d get their name on the CD. So a thousand people theoretically put in $40, and he raised $40,000 to fund his own CD independently through that. [Andrew’s note: individuum‘s Academy Of Dreams sponsored $25,000 of the $40,000 total]. I think that’s just something to think about: you [the musician] have the ability to create a community.

The other thing that’s interesting is that the notion of status in our society is changing a lot. Status symbols used to be – I read this is a Sunday Mail article, so I don’t know how great of a reference it is – it used to be that if you had a gold Rolex watch, or a great house, that was a status that people would care about, that you’d show off to your friends. Now I think what’s happening is that status is more about the experiences that you have, and the ones that you can talk about. So if you went on a spaceship to the moon to have a party with U2, that would be something that would impress your friends, if you see what I mean.

I think that what’s happening with festivals, why they’re succeeding so much, is that it’s not just about the music, it’s because you’ve got to tell your mates that you went to Big Day Out, or you went to Splendour [In The Grass]. It’s like a badge of honour. I think the other thing to keep thinking about is how you can create something that gives people that sense of good feeling that they experience.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Please don’t tell me that you think the future is frickin’ Twitter. Paul, where do you see the future of music going?

Paul Paoliello – CEO, Mercury Mobility [pictured right]:

Obviously, the barrier to entry to the music industry these days is a lot lower due to technology. Anybody can get into the business, but the bottom line is still around creativity. You cut through in this industry via your creativity. If you have something special musically, it’s going to cut through, but also in terms of reaching your fans; these days, it is about getting creative around building those communities, as the other guys have been saying. So the approach to this business, or career that you take, or this art form that you’ve embraced around music – it is more of a business, and you have to embrace it. Because it is so complex.

Obviously, the barrier to entry to the music industry these days is a lot lower due to technology. Anybody can get into the business, but the bottom line is still around creativity. You cut through in this industry via your creativity. If you have something special musically, it’s going to cut through, but also in terms of reaching your fans; these days, it is about getting creative around building those communities, as the other guys have been saying. So the approach to this business, or career that you take, or this art form that you’ve embraced around music – it is more of a business, and you have to embrace it. Because it is so complex.

The exciting thing is that you can take a more ‘do it yourself’ approach with music. There are many tools out there that enable you to create music, and to connect with a fanbase. And to monetise your music, whether it is, as Rick said, coming up with an interesting concept to get your fans to help you fund an album, build an album, sell a download, build a mobile community, or whether you want to get your music on iTunes. There is no barrier to entry to getting a sales channel for your music, these days, but it really does come down to being a lot more savvy around the music industry, and how to build a career around it. And as you go, to build up as much leverage as you can around your intellectual property – your music and all the things associated around it – and obviously, the multiple revenue streams that you are driving from your music. Whether it’s your recordings, or your t-shirts, your whatever; the more leverage you have, I guess that becomes the enabler for your future relationships with the broader industry. And that’s when the major record companies come along, and they start knocking on your door, and you’re in a stronger position to decide whether you want to work with them or not.

These days, they [major labels] are really the bank that you need to make a big hit bigger, or a big business bigger. As the guys were saying, the major record companies are trying to keep themselves afloat, so they are trying to grab hold of what everybody’s calling the 360 elements of the industry. But they don’t necessarily have the skill set, or they, like everybody else, try to get fewer people to do more work, with less skills. So it becomes a lot tougher. But if you are driving those revenue streams, and if you are in a lead position, then you are in a much stronger position to determine whether that relationship works for you, on a 360 basis. Or whether it is only 270, or 90, or 10 [degrees].

And I guess, having left the music industry in its tradition form and gone into mobile, my feeling was that getting into digital, I needed to build my skill set around this ‘brave new world’ that digital and mobile is becoming. In the last couple of years, as Lars was saying, it really is the tip of the iceberg. As Lars was saying, it hasn’t matured in any way, shape or form. Digital is very much driven by iTunes. Mobile is very much driven by the iPhone. And with the new application landscape, it is driving what mobile is essentially going to become. And that’s the exciting part. That access to music on-the-go, and having a device that is going to be all things to you.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Okay, I’ve got to tell you that the future of music will have a lot to do with mobile handset manufacturers. I’d like to share my vision on the future of music with you, from an old fart who’s been around in the industry for 38 years. 38 years ago, when I got out of the drug trade – I mean when I got out of the fine stone trade – I was living in a small place in Atlanta, Georgia, on 14th Street, which was about one block away from Piedmont Park. One Sunday, when I woke up at about one o’clock in the afternoon, I heard this great music. I heard a guitar playing like I’d never heard, and two drummers. I walked down to the park, and there they were, in the gazebo: The Allman Brothers Band.

They were playing every Sunday, live, free, and they were building a music community, at that time. That was almost forty years ago, and they’d been going for two years prior to that. When I was in the States last at SXSW, they did a run of the Beacon Theater in New York. They do it every year, maybe ten shows, over a two week period. And they sell out instantly, because they’ve maintained that community over many years. People believe in them, people who know their brand, wear their t-shirt, buy every single live album they ever do; they buy anything. There’s even a magazine devoted to them, called Hittin’ The Note.

The future of music is this. I’ve experienced it and I love it. I buy music, I don’t download stuff for free. I don’t want worms, and all that other stuff [Andrew’s note: he is referring to viruses]. I want either FLAC lossless, or I want 256k downloads. And I’m not going to be getting that from all of my iTunes purchases. I don’t purchase here. I don’t mind saying it: I don’t buy Australian music. Most Australian music is for you people, the younger people. The last Australian band I bought was The Greencards. I have four of their albums. Most of you wouldn’t think of them as Australian music, you’d call it ‘bluegrass’.

Truth of the matter is, I buy about $5,000 of music each year, and it’s not just iTunes. I would love for you to go home tonight and go to a place called Munck Music [munckmusic.com]. It’s based in the US, and created by a producer and an engineer who believe that if they recorded bands and offered their live music for sale to their fanbase, they could make a lot of money. Especially if like, Little Feat, they have a hundred concerts out there. Bruce Hornsby has about 50; the entire New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival has a couple of a hundred shows by artists up there. The Grateful Dead, and others [do too], including The Allman Brothers Band.

I’ve purchased probably 20 Allman Brothers concerts, 20 Little Feat concerts, 10 Bruce Hornsby concerts, and you can get them one of three ways. CD: $14 (USD) for a concert, usually three hours’ worth. Secondly: as a 256k download. You can sample the music, you can view the setlist, so you can see and hear what you’re going to get. You can also get it as in the FLAC lossless file format, which means that it’s not ‘2 per cent milk’, like MP3s are; it’s more like ‘full-cream milk’. It takes a long time to load, and you better have a big account for it, and a large storage device. However, these bands have made a fortune from selling their own music to their own fanbase. And they also go on cruise ships, and take their fans around to Jamaica, or up and down the Mexican coast, or through the Caribbean, doing nothing but cruise ship shows, full of fans.

The other place you’ve got to go is called Moogis [moogis.com]. It was started by The Allman Brothers’ drummer, Butch Trucks, who had an idea that when technology and downloads could meet the need for video and audio to be compressed reasonably, and give high quality, then that would be the time for a band to be able to sell a subscription to their six months of concerts, for users to pay $100 to see that show as much as they want. With backstage footage, various camera angles, and the full concert, in high definition, and with high quality audio. So Butch and the band started selling that, and I don’t know how much they’ve sold, but it’s worked for them. They’ve done extremely well.

But to me, and you, the future of music is being able to create a brand with your band. Create an audience, and keep them as a community. Don’t ever lose that community you have ‘back home’, just because you want to go overseas and make it rich. The day you lose that is when you lose your career. [The future is] Selling your music directly to your community in any form you can, and especially if you’ve got a great song, selling it to them in ten different ways. Extended ways, mixed ways, whatever.

The future of music is going to be about you knowing the business of music, too. Because without the business and the understanding of copyright, commerce, and a lot of other issues, you’re not going to be able to succeed. So I suggest that you line my pockets by coming to my conference, in August, because my future of music is dependent on you, too.

The future of music of music for you [the audience] is this: get a job. Work with people who inspire you, and pay you fairly. And can give you the opportunity to do things. Don’t necessarily work for free, but ask lots of questions, take lots of notes. Watch, observe, and above all, be honest.

What we want to do now, because you’ve been such a great audience, we want to answer any question you’ve got about the music business, or anything else you’ve got.

Paul Paoliello – CEO, Mercury Mobility:

Phil, just one thing. Google ‘Trent Reznor‘, because there was a case study that was done earlier this year at Midem, the music conference at Cannes that they have each year. They studied Reznor, who basically decided to revive his career, and looked at the whole digital model, and did a combination of offering his albums for free, offering limited editions, box sets, digital versions, hiding USB sticks at concerts, special versions hidden in storage drains as a treasure hunt based off his website. It’s a really interesting case study who is interested in trying to enable their fans, and keep their fanbase loyal, and building around that model.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Music should always be about discovery. Questions, please.

[Audience Q&A section commences. It comprises four questions and is fifteen minutes in duration.]

Question 1: Just on Trent Reznor – if you look up a Digg interview with him, he talks about his entire business model, and it’s fascinating. My question is regards to copyright law: what do you think the future is going to be? How are copyright owners going to enforce their copyright? Will it go more toward the Creative Commons?

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

They can take my copyright pen out of my dead hand, clutching it to the very bitter end. I’m gonna fight for copyright. Look, I have intellectual property. It’s boring, but it’s very lucrative, and my intellectual property has nothing to do with songs. I think copyright will continue to evolve, but unfortunately it will evolve very slowly, and far behind the ability for people to steal. Just like they haven’t figured out a way to stop people shoplifting yet, have they. Paul?

Paul Paoliello – CEO, Mercury Mobility:

Yeah, I was just going to say the same thing. The minute you open that door, the floodgates open, so they’ll never be able to move with the times. Country by country, it’s going to be different. That’s where a lot of the ISPs are getting frustrated, the Yahoos and Googles of the world, because they’re saying “well, cross-border, we’re trying to do this as a global thing, to try and clear copyright across borders, but we just can’t do it”. It’s still remaining territorial. Some territories are going to be more open to change than others. Here in Australia, they’ve been trying to change the law the for a while, and the cogs are still turning.

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine:

I’ll jump in here. I think that Creative Commons is a wonderful opt-in solution for people who want to allow anyone to use copyright. When the music industry initially shut down Napster, we saw Lars Ulrich speaking on the movie earlier. He made himself an enemy to a lot of people worldwide who wanted to use Napster to disseminate their music. So that a kid in Atlanta could be heard by someone in Peru. There are now platforms which allow you to do that, but I think that Creative Commons underwrites that, and enables people to create that copyright.

But coming right back, absolutely, I don’t think copyright rules will change any quicker than snail’s pace, but anyone who has a vision and wants to create, should have the right to patent it and receive royalties, at least while they’re walking on this planet.

Question 2: Do any of you have any concept – because I know it’s variable – just roughly what artists are getting percentage-wise for music downloads? Is there some ballpark figure to get ideas?

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

If you sell music on iTunes, they’ll take their cut, which is 30%. And then the distributor will take their cut – typically between 20-25%. And then the artist gets the rest, so in the case of an iTunes sale, the artist will receive 70 or 80 cents per song. Which is actually quite good, because there’s nothing physical that’s being created, and you’re getting this invisible sale. The latest statistics show that only 5% of music online is bought, and the other 95% is ‘taken’.

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine:

We also have to look around at other ways of generating alternative revenue streams. There’s a fascinating case going on at the moment with YouTube, the user-generated content platform, and some of the major record labels who’ve nixed any of their content that’s available on YouTube. Warner Music‘s one of them. So we’re looking at transactions on iTunes as one way to make money, but in the years ahead, if your music is being used on these user-generated content platforms, you ought to – in theory – earn a cut of advertising revenue on that platform. This space is changing; there is money to be collected out there, but it gets very confusing, and very complex.

Paul Paoliello – CEO, Mercury Mobility:

Just on that, Gavin from Sony BMG often quotes a Justin Timberlake cases. When they brought out his last album, they found about 120 revenue streams for that album, at last count. So from a ringtone to a full track download, to a YouTube revenue stream, to an online radio stream, to a CD sale, and so forth, there was 120 different revenue streams, for that one release. And that was a couple of years ago, so these days, it’s probably even greater.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

The other side of the equation is – to answer your question more directly – it depends on how smart or stupid you’re going to be in assigning your music to someone to sell it. We use the term ‘aggregator’; these are people who take your music and place it on a variety of different sale sites. Some of them take a very small amount, such as Tunecore, who charge a flat fee to put the music up; they don’t take a percentage. Whereas others charge large fees and take large percentages, and don’t necessarily always report to you. There’s CDBaby, for example, which has been around for a while, and IODA, and Amphead.. I wouldn’t necessarily recommend the Australian alternative. The Orchard.. I’m ambivalent [toward them]. But the thing is, there’s a lot of people waiting to rip you off, just like there was with the compilation scams of many years ago. “Get yourself on a CD that we send around to all the A&R people, for a fee.” Be very aware that if people are trying to charge you a fee to put your music up on iTunes or wherever, you should very carefully check into them. Fortunately, it’s a lot easier these days to find out.

Question 3: Something the film didn’t really didn’t cover is the role of the ISPs. I know from conversations that I’ve had with people from APRA, and that sort of thing, that they are trying to negotiate with ISPs to come up with a solution to this. What are your thoughts on the role of the ISPs in Australia?

Lars Brandle – Australasian Editor, Billboard Magazine:

We understanding of the argument is that ISPs are the ones who are getting the benefit of all the music being there – people going there [online], and getting free music – and of course the ISPs are getting their subscription. And the value of that subscription is incredibly valuable, given that you can get a whole lot of free music by going online. One solution that’s being offered up is that the ISPs are forced, in some ways, through some legislative creation, to track all of the downloads, including the free ones, and somehow compensate the artists. Similarly to the way APRA does, through the form of either radio or live [performance royalty fees]. This is just one of the possible solutions that are there; whether it will go down that way, is questionable.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

APRA is a great organisation that has done an incredible amount for the music industry, from bringing court cases and seeking judgements from tribunals, and increasing the amount of money that is paid to the composers, the songwriters, and their publishers. It’s a shame that the PPCA [Phonographic Performance Company of Australia] and ARIA [Australian Recording Industry Association] haven’t had the vision, the forethought, or the ability to do much more than ‘sweet FA’. As a result, fortunately, composers, songwriters and their publishers get paid. Artists often do not. And one of the interesting points that’s raised about this is that with all that money that was awarded to the record industry on the Kazaa case, the $54 million: artists didn’t see that money, and they won’t ever. One more question.

Question 4: Okay, just before when you were talking about the royalties, about how artists generally get nothing, and where they’re making their money is through live performance.. why should we really care that we’re downloading their music for free, and giving it to other people? I would not know half of the artists that I know through free downloads, if it wasn’t available to me for free, because I wouldn’t be able to afford to go out to the stores and buy it.

So in essence, when I’m giving all my free downloads to my friends, and the ‘word of mouth’ thing is working, and we’re all going out to the live performance when they come to town, and there’s more requests for them to play because we’ve had that whole word of mouth.. why should we really care if we’re really giving our money back to our artists anyway? Aren’t we kind of bypassing giving our money to the corporations and the record labels, by not buying their CDs?

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

I heard it best said that “you may consider yourself to be an auto-enthusiast, because you like fast cars. But when you decide to steal that car, you are a thief.” And it’s not necessarily going to enrich General Motors, Porsche, or whatever, that you decided to steal that car. Now, what you just said made a lot of sense. A lot of people who download music do buy it. They do discover it that way. However, I really don’t believe that people like you are gonna be that generous when it comes to actually paying for things.

Now, the same people who download music [for free] are the same people who try to get into clubs for free – get on the ‘free list’ – and stand outside the fence at Splendour In The Grass. The same sort of people who want to wear a phony t-shirt of a band, because it costs a lot less than the real thing. I do take your point that you are trying to discover music, and hopefully it [Andrew’s note: money, presumably] will reach the band. But I’ve been in this business a long time. I don’t see anybody out there who does ‘sonic shoplifting’ that really thinks altruistically about ‘the brothers’ in the bands.

Rick Chazan – Manager, The Boat People:

I agree, and I’ll add to that. What you’re saying is that it’s actually not bad for the bands, because by allowing it to be free, you’re actually discovering the bands and therefore, you can love them and maybe go and see a live show, et cetera. And so you’re saying therefore, it’s okay. But it’s got to be the artist’s choice that it happens that way. You’re still taking something which they’ve created and paid for, and put time and work into, like anybody doing anything. And for example, you might discover that music on MySpace, which the artist chooses to allow to be free; [to be] streamed, not to be stolen of off. You can learn about the artist through five or six songs; I know in The Boat People’s case, we’ve got five or six songs up there from the last two albums, so there’s a bit of a mix to get to know the band. You could listen to it all day long, and get to know the band, and want to go and see them live. And if you loved them enough, you’d actually have to have that CD.

As an independent band, we’re losing that opportunity, and I don’t see it [inaudible]. I’d hate to come across as a moralist, but I have a problem that what’s being lost in the whole conversation is that it’s now being said that, because it’s easy to do, and everybody’s doing it, it’s ‘okay’. So it’s like, nobody’s saying to a young person, “look, this person actually toiled, they put their work into it, their effort into it, therefore they actually have value in it, and therefore to enjoy that, you need to actually trade for it”.

Now it’s being said that because it’s so easy and because it’s so bloody hard to do anything about it, it’s ‘okay’. So, to me it’s not all about criminalisation, because I think that’s a waste of time, to sue some individual teenager for downloading a song. But it’s more about conscience. It’s more about, you know, when they asked the people in the movie, “who downloads music for free?” and all of their hands went up, and then they asked, “who thinks they stole the music?”, or did something wrong, and it was only one out of a hundred.

See, I know about this a lot better than anyone, because when I was a teenager I used to record tapes. I used to do that, because I really wanted the music [from the radio], and I didn’t have enough money to get it. But I knew that it was wrong, and I did feel a little bit like my conscience was saying “this is not quite right”. I feel that we’re eventually going to the lose the consciousness of taking something from another person, and that’s the part that disturbs me.

Phil Tripp – Managing Partner, IMMEDIA!:

Great, that was perfect. I have one other thing to say. It’s kind of like: if you think you can get somebody drunk enough at a bar that they’ll screw you because they have no more control over themselves, that’s about the same way that I equate the moral ability to download music. Because you think you’re going to give somebody else a good time. That was a good one, wasn’t it? (laughs)

[Audience Q&A session ends.]

Download Phil Tripp’s introductory speech

Download the panel discussion (I transcribed from 26th minute until the 67th minute)

Download the Q&A session

The film will screen in Brisbane at UQ‘s Schonell Theatre from June 4, 2009.

First Three Songs, No Flash – And No Copyright

First Three Songs, No Flash – And No Copyright

I think it really depends on what you want to do. You get out of it what you need to. For certain jobs, it’s still quite necessary. I didn’t go the standard MBA route, but I did get a ton out of my experience, with two key points:

I think it really depends on what you want to do. You get out of it what you need to. For certain jobs, it’s still quite necessary. I didn’t go the standard MBA route, but I did get a ton out of my experience, with two key points: On copyright-related issues,

On copyright-related issues,  I think there are two key issues:

I think there are two key issues:

The future of music, the way we look at it, is about going overseas. But not giving up your home country. You hear my American accent; I’ve been here 28 years, and I always love to come home to Sydney. And for the set of trips that I’m doing this month, I found a film at South By South West (

The future of music, the way we look at it, is about going overseas. But not giving up your home country. You hear my American accent; I’ve been here 28 years, and I always love to come home to Sydney. And for the set of trips that I’m doing this month, I found a film at South By South West ( As far as music mobile for

As far as music mobile for  That’s just making me think; going back to the movie, there was that comment about how the future of music will be less creative, because of the locks that are being put on copyright. But here’s this band, Blame Ringo, who have just shown us that if you’ve got a good idea, and if you can follow it through, and make it happen on a world stage. The technology’s in your hands. You don’t have to grab someone else’s inspiration, and rework that; if you’ve got an idea in your head, then you’ve got the tools to make it happen. So I don’t agree with that comment, that ‘the future will be less creative’. I think that’s wrong.

That’s just making me think; going back to the movie, there was that comment about how the future of music will be less creative, because of the locks that are being put on copyright. But here’s this band, Blame Ringo, who have just shown us that if you’ve got a good idea, and if you can follow it through, and make it happen on a world stage. The technology’s in your hands. You don’t have to grab someone else’s inspiration, and rework that; if you’ve got an idea in your head, then you’ve got the tools to make it happen. So I don’t agree with that comment, that ‘the future will be less creative’. I think that’s wrong. Well, there’s no doubt that the dissemination of information is definitely changing. We’d be fools to not realise that. We haven’t rushed into a web presence. I mean, we’ve got

Well, there’s no doubt that the dissemination of information is definitely changing. We’d be fools to not realise that. We haven’t rushed into a web presence. I mean, we’ve got  Obviously, the barrier to entry to the music industry these days is a lot lower due to technology. Anybody can get into the business, but the bottom line is still around creativity. You cut through in this industry via your creativity. If you have something special musically, it’s going to cut through, but also in terms of reaching your fans; these days, it is about getting creative around building those communities, as the other guys have been saying. So the approach to this business, or career that you take, or this art form that you’ve embraced around music – it is more of a business, and you have to embrace it. Because it is so complex.

Obviously, the barrier to entry to the music industry these days is a lot lower due to technology. Anybody can get into the business, but the bottom line is still around creativity. You cut through in this industry via your creativity. If you have something special musically, it’s going to cut through, but also in terms of reaching your fans; these days, it is about getting creative around building those communities, as the other guys have been saying. So the approach to this business, or career that you take, or this art form that you’ve embraced around music – it is more of a business, and you have to embrace it. Because it is so complex. Streaming concert video hub

Streaming concert video hub

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was

If I had to give you a number, I’d say we’ve moved the strike rate from something like 10% to 40%, which given the number of bands that comes through Sydney is a significant figure. We just filmed our 500th show, which was

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

I have a ridiculous amount of music stored digitally, both burned from my vinyl and CD collection and bought from iTunes.

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.

Thanks! It was great to be acknowledged by our peers as doing something worthwhile.