A Conversation With Damian Kulash, OK Go singer/guitarist

OK Go are an American pop band. I don’t want to cheapen their career by naming just its apex, but it’s the easiest way to refresh your memory: they’re the band behind ‘Here It Goes Again‘, better known as ‘the treadmill video‘.

OK Go are an American pop band. I don’t want to cheapen their career by naming just its apex, but it’s the easiest way to refresh your memory: they’re the band behind ‘Here It Goes Again‘, better known as ‘the treadmill video‘.

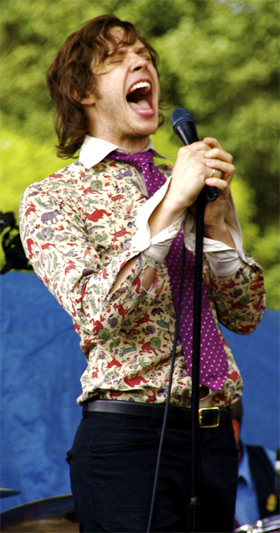

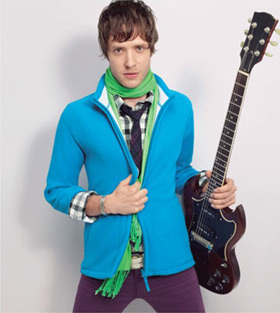

On February 13 2010, I spoke to OK Go’s singer/guitarist Damian Kulash [pictured right] on behalf of Rolling Stone Australia. He’d been up all night shooting a second music video for their song ‘This Too Shall Pass’. The first video couldn’t be embedded anywhere outside of YouTube because of the restrictions put in place by their parent label, Capitol Records, which is owned by EMI Music. The band’s response was to upload an embeddable version to Vimeo, write an open letter to their fans explaining the situation, and seek outside funding to conceptualise and film an entirely different music video. [You should click the above links to watch the videos, if you haven’t already seen them.]

Shortly before Rolling Stone’s May issue went to print at the end of February – confusing, right? – OK Go left Capitol Records, effectively undermining my story’s relevance. [More on that experience here.]

Below is the full conversation I had with Damian, which is one of the last interviews the band gave while still signed to a major label.

Andrew: Before we start, are you totally sick of talking about this whole issue?

Damian: The politics of the music industry are… tiresome. I’ll put it that way. It’s important to me and I’m fascinated by it, but I’d much rather be thinking about making things, than how to distribute them.

What kind of response have you seen from your fans in regard to your letter?

It’s been pretty positive. My letter has been received by some people as a polemic, or as a big screed, but truly, the letter was just an explanation to our fans about why certain things weren’t available to them, because I think people really didn’t understand what was going on. I didn’t see it as a big political move; it was just an explanation to our fans, and we’ve gotten very good response from them. I think they’re just happy that we treat them like adults.

What kind of response have you seen from the record label? I read your interview on New TeeVee where you said your main contact at the label wants as badly as you do for the video to be embeddable.

I think most folks at the label probably share our opinion that things should be easily distributed. There are a lot of competing agendas within the record label, so I’ve gotten a wide range of responses. The digital department of EMI France actually tweeted the letter and was distributing it because they felt it was a defense of their position. Other people felt like it was an attack. It’s a big company, so there’s been a wide range of responses.

Beyond your fan base and record label industry people, the general public has also paid attention to the letter. I refer to your quote in Time about how you think there is a quiet majority who are just interested in seeing how the music industry works these days, and seeing your explanation from the inside.

That’s definitely been the basic response that I’ve felt. I obviously can’t quantify it, but the loudest comments in the music industry in general are mostly from people who hate labels and who hate major labels and feel the industry is set up to screw musicians. I don’t feel like that’s generally representative. I think it’s easy to hate the machine. You really get those comments from people that actually try to make a living making music. It’s mostly people who have this purist idea of what music should be to them; give up their day jobs because they want their musicians to be absolutely conceptually totally pure and not ever have to worry about money for them.

I read your Mashable interview where you said that a year or two ago, EMI switched the embedding stuff on all of your videos, but you didn’t pay much attention as you were making your new record at the time. Looking back, do you wish that you had paid attention? Would you have done anything differently back then?

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world.

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world.

I’m glad that when I’m writing music and recording music, in between records, I’m not spending my time trying to figure out the solution to the logistical problems of the music industry. Those are some things that we have to pay attention to out of necessity, not because we like paying attention to them.

There is a quote from you in the letter where you say, “Unbelievably, we’re stuck in the position of arguing with our own label about the merits of sharing videos. It’s like the world has gone backwards.” As musicians, you must feel that having these kinds of conversations about the business side of music drains your creativity or your time that could be better spent creating music.

It seems to me like there are a couple of things. One, the music industry is very clearly in an incredible crisis and that’s what makes this story complex. There is a lot to talk about because we’re up against what appears to be a sort of unresolvable problem. People want to talk about it. Two, I think a lot of us feel incredibly passionate about music and by its nature – almost by its definition – the important part of music kind of defies words. To me, what makes music sort of magical – what makes music the thing that I live for – is that you can communicate things like music’s four-dimensional emotions instantaneously. It’s like emotional ESP.

I think when something comes along, something to talk about in music, something very rational or logistical and sort of left-linear logical, that’s attached to the distribution of music or to the manufacturing or production of music, then at least there is something to sink our rational brains into and some people really want to talk about it. Maybe this is something of a stretch as an argument, but we do a lot of interviews and it’s impossible to answer substantive questions about music because music is a feeling, not an argument. Whereas, everything that surrounds music – how it’s distributed, the politics, and the money behind it – gives you something hard and logical to talk about. I think that’s sort of why there is so much fascination on these things.

Bob Lefsetz wrote in response to this situation that “if the labels want to maintain control, they have to first get the hearts and minds of the artists.” As an artist who deals with labels on a regular basis, do you share his view?

Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think.

Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think.

Twenty, fifteen, or even ten years ago, music was a physical thing that could be bought and sold. Even if conceptually the music wasn’t, there was a way of controlling access to it: you either owned a CD or you didn’t. Either you had access to it or your friend did, or you got it from a library. More likely, you bought it and had access to music.

Now that has sort of broken down and the music industry is not going to be able to get that genie back in the bottle. You have to find a different level to work with, and I think that – whatever the financing situation is, no matter which body is financing the logistical mechanics of music – that body will have to have a better relationship with musicians and record labels. Record labels deal in very black-and-white terms with this restricted access thing, and now everyone is going to have to believe in a new model simultaneously, otherwise money won’t be generated for music.

By now you’re all too familiar with the arguments surrounding this YouTube issue, having lived them out and told the world about it. If you can comment on it, I’d like to know how EMI rationalise the ‘disable embedding’ decision to the average web consumer – the one who just wants to share their cool videos with their friends?

There has been a conceptual shift between videos being advertisement and videos being product. They’re sort of ‘on the fence’ still. All labels still want their videos to be seen far and wide, but they also want to be paid for them to be seen far and wide. Whereas once upon a time it was just amazing that there was a website out there [YouTube] that would actually help you distribute your advertising. Now, there is a website out there that is actually distributing your product without paying you for it. I think that’s how they justify it. They want people to see it like: “we paid for that thing, how come you won’t pay us for it?”

Do you think that the thought of the average web user even comes into their equation, or is it all just discussed in terms of profit and shareholders, as you alluded to in your letter?

They’re not such morons that they can’t take into account what people want. Labels don’t have a singular mind. It’s not like one big beast with one agenda. I think a lot of people at labels understand what people want and are frustrated with the way things are working. I think there hasn’t been a very clear-eyed assessment of that shift in music videos from advertisement to product, or in general, of the attempt to blur promotion and monetization. There used to be an obvious revenue stream, and that was selling records [CDs]. Since that is shrinking so incredibly fast, now all the things that you essentially pay for to promote that revenue stream are now things that they’re trying to turn the tables on and get money for actually having done.

I don’t think they’re incapable of thinking about what people want. I think everybody suddenly is trying to eat the hamburger at the same time that they’re still milking the cow. You can’t have it both ways.

Final question Damian, and it’s a bit of a philosophical one, so take a deep breath. If labels continue to herd viewers into absorbing their artists’ content in specific web destinations like on YouTube, what are the wider ramifications for the nature of sharing content online?

First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

If we don’t want to be just a domain of the independently wealthy and people who can take time off from their jobs for a couple of years to see what happens, or finance their own world tour while they figure out exactly how to make the number at the end of the column black, then somebody has to be doing this risk aggregation.

Historically, when a band did well, or an artist did well, the profits could be so substantial that they would cover the other nineteen losses that the failed bands meant for a record label. A label could take the very extreme numbers of the music industry: you might have a less than 1% chance of success, but if you do succeed there is a massive reward, and it sort of evens them out over dozens or hundreds of artists a year.

Something sort of needs to be doing that unless we want music only to be the domain of the independently wealthy. I think then you have to figure out what that means for content distribution. Somehow, some sector of the business has to be able to make a significant reward off of the success of that one-in-twenty, or that one-in-fifty, or that one-in-one hundred in order to keep the system running.

At the same time, we all want this magical, wonderful, instantaneous global distribution – via the internet – to make music ever easier to get to and to make it more universal and more accessible. We have to figure out how to get the money that people are willing to spend on music into the hands of musicians, and into the hands of those risk aggregation bodies.

Right now, it seems people are willing to spend money pretty freely on music. They just tend to do it more on hardware or on their broadband connection. People are willing to pay for extremely fast connection to the internet so they can download big files. They just don’t particularly care for paying for the file themselves, or see that as something they should be doing. People will pay a lot for an mp3 player. They don’t expect that part to be free, so to get people to value their music in that way, then we should figure out how to look at the system from a macro perspective and figure out a reasonable way forward.

Thanks Damian. I admire your ability to speak coherently about the music industry, especially after an all-nighter. [The band had been up working on the second video for ‘This Too Shall Pass‘, which is embedded below.]

I don’t know how coherent I’ve been, but if you can whip that into shape and make me sound like I was, then more power to you. I appreciate it.

[You can read more about this story for Rolling Stone Australia here.]

Regardless, Jackson’s enormous sales in the US simply couldn’t have eventuated ten years ago. Record stores inventories would’ve been exhausted across the country, and compact disc factories would’ve rushed to press more discs to meet the demand. Both of these outcomes still eventuated, but instead of experiencing weeks-long delays, music consumers have the option of instant online gratification: his 2.3 million download count resulted in six Jackson tracks appearing in the Billboard top ten.

Regardless, Jackson’s enormous sales in the US simply couldn’t have eventuated ten years ago. Record stores inventories would’ve been exhausted across the country, and compact disc factories would’ve rushed to press more discs to meet the demand. Both of these outcomes still eventuated, but instead of experiencing weeks-long delays, music consumers have the option of instant online gratification: his 2.3 million download count resulted in six Jackson tracks appearing in the Billboard top ten. At a national level, ARIA’s

At a national level, ARIA’s  To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first.

To elaborate on the latter example: picture the average album you’d buy from a store – perhaps not in this era, since both CD shelf space and CD merchants continue to dwindle – but ten years ago. Hypothetically, the disc is likely to be front-loaded with some great songs. They’re the ones that you’re likely to have heard before you bought the album. These strategically-placed songs are the ones that either – or both – the band and record label wanted you to hear first and enjoy first. That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s.

That listening habit was exploded when CD burning technology allowed listeners to compile the circular equivalent of mixtapes, without the cassette-associated fuss. As the audio filetype known as MP3 became easier for the masses to acquire online, consumer attitudes to music further deviated from the past when the first digital audio players became available in the late 1990s. In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept.

In 2009, artists shouldn’t automatically sprint toward the album endpoint as a result of historical programming. Their creative output shouldn’t be stretched to meet the 45 minute/12 track (whichever comes first) expectation, just so that the parties involved can proudly call it an album. In an era where more music is being written, recorded and performed each day than at any other point in history, an artist shouldn’t throw together words, chords and beats just to meet an expectation built upon a decades-old concept.