A Conversation With Benjamin Law, author and freelance journalist

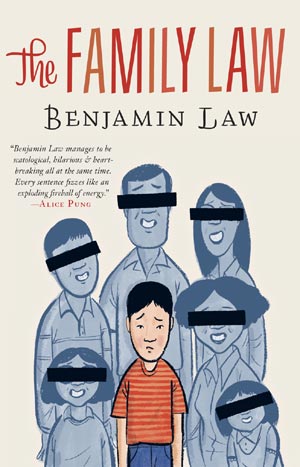

Benjamin Law [pictured right] is a Brisbane-based freelance journalist (for Frankie, QWeekend, and The Monthly, among others) who recently had his first book, The Family Law, published via Black Inc. I interviewed him for The Courier-Mail about its genesis and release; you can read that story here.

Benjamin Law [pictured right] is a Brisbane-based freelance journalist (for Frankie, QWeekend, and The Monthly, among others) who recently had his first book, The Family Law, published via Black Inc. I interviewed him for The Courier-Mail about its genesis and release; you can read that story here.

What follows is a transcript of our conversation, which took place in late April in a New Farm coffee shop.

Andrew: So I read the book, and found it pretty damn enthralling. The way you tell stories is quite engaging. I like how you switch between first person-like dialogue, then switch away to tell a story.

Benjamin: Thank you very much.

I saw you had your first review.

Yeah, in Bookseller & Publisher, so that’s mainly an industry magazine, but that’s important and a relief because I know from working at a bookstore, Avid Reader, that magazine’s important to know how to sell things and whether to sell things. So yeah, pretty chuffed.

How does your family feel about the book?

It’s always the first question, isn’t it? [laughs] Well, I’ve written about my family a lot because I write for a magazine called Frankie, a lot of those first person sort of stuff, a lot of it is personal anecdotes, funny stories from your life, and pretty short funny essays that a lot of other writers write for Frankie as well, so not just me. I’ve been writing for them for quite a while now, so my family is quite used to me writing about them.

They’ve gotten accustomed to it, and to be honest; we’re a pretty open family when it comes to most things. You’ll read the book and you’ll hear the stuff that my family says. It’s pretty outrageous. If you’re a friend of mine and you’ve met my mother for the first time, most of my friends have a story of when they met my mother for the first time. They can usually pinpoint the exact moment where she started talking about all of our births, in graphic detail. It’s not a very closed family. There is not much that’s too sacred, really.

When I was writing this book, it was funny; I got a book contract, and I said, “Hey guys, I’ve got news for you all.” They were like “What?” I’m like “I’m going to write this book,” and they were all like “that’s amazing, what’s it about?” “It’s about you guys.” They were like “That’s … really good.” You can sort of see it’s really great because whenever my family, especially between the siblings as well, are completely different but everyone does really well in their field and we really celebrate everybody’s wins, so when I said I’m writing a book and I’ve got a contract for it, everyone was over the moon, thrilled.

I think when I said, “Guess what it’s about,” they were like “cool,” but when I finished the draft, all 6 of my immediate family members – I sent a draft to all 6 immediate family members and they liked what they saw. I think because I’ve been writing about them for a while now, I’ve got an internal gauge of what I can and can’t… To be honest, the stuff that I wouldn’t be able to get away with wouldn’t be that interesting anyway.

When they read through the drafts, it was mainly stuff like “Change some of your spelling, your grammar is wrong here, your syntax is a bit awkward here”. They were just like “You know what, this is totally fine.” There were some disputes as to how things happened. There were some discrepancies in memories as well, in terms of whether this happened, how it happened, what people said, and that’s because it’s so long ago. These are stories going back through the ‘80s and ‘90s, which is when I grew up. Beyond that there wasn’t too much of a problem. Everyone is pretty happy.

So you weren’t taking too much creative license with these stories; you tried to faithfully recreate them as they happened.

As faithfully as possible, totally. Names have been changed and I think there are some pretty obvious reasons why some names have been changed. All my family have been pretty happy to stand by their names and their dialogue. I’ve tried to make sure they sound as natural as they can; I obviously didn’t go back in time and record their dialogue. I didn’t take too much creative license and everything that happened in the book pretty much happened.

It’s interesting to me that you didn’t actually talk about the act of writing about the family at any stage during the book, so it was all from a distance. You recounted a story instead of saying “I was thinking at the time I’m going to write about this afterwards.” At what stage did you start writing about the family in Frankie?

I think I started doing a creative writing degree and I think I reached a point where I realised my family’s material was pretty good material. When I was doing my creative writing degree, everyone was writing fiction. I realized I’m rubbish at fiction. All of my fictional works were thinly disguised memoirs. I think that’s what a lot of people do for their first novel; they write a thinly disguised memoir.

I thought I would instead write it straight because especially after you read this book and a lot of other memoirs, sometimes fact is stranger than fiction. I think with my family at least, that’s often the case. You’ll come across stories that defy belief a little; my dad meeting his dad for the first time after a decade and his dad dying that very day. That seems beyond anything any fiction – if you wrote that as fiction it would seem contrived.

I think there is something cool about writing it straight. At what point did I decide to write about them? I think I’ve been writing about them in one say, shape, or another throughout the years, but I think Frankie sort of gave me the opportunity to write about the stuff that’s happened but also through a humorous lens as well. There is some stuff in the book that’s quite heavy but I think unless it’s coupled by humour, it doesn’t really work. I think that’s one thing my family is quite good at, all of us, we like laughing at horror, at least after a while. Everyone has a pretty black sense of comedy.

What was it, that Minnie Mouse rape story…. “I was raaaaped!”

[laughs] That comes early [in the book]. That’s dark. We weren’t sure whether to include that or not, but I just left it in after a while. If I wouldn’t have left that in I don’t think you would have gotten a very true sense of how inappropriate my family can become.

Have you ever kept a diary?

No, I’m really undisciplined. I’m incredibly undisciplined. You would talk to a lot of other writers who would say, “I’ve kept a diary since I was a child, and then I kept a lock on it under the bed.” I went back to my family house recently and I found an old diary and like all of my diaries from childhood, all of January is filled, and then the entries become bullet points, and by February I’ve given up.

I don’t know about other people but I never thought as a kid that when this stuff was happening that it was incredibly interesting. I was born into a big migrant family, into a pretty odd family in a lot of ways, but I never thought it was that unusual or interesting to write about. I think you build up that self awareness later in life. I’m not a disciplined enough writer to write every day. It’s interesting; writing these stories has been – it’s not until you start writing them that you start remembering some of the details that come through.

And your family’s feedback would have assisted along the way.

That’s right, after the first draft.

Speaking about heavy topics, the chapter about how parts of your mother’s family were deported to Hong Kong, that was heavy and to get that kind of perspective, for me as an Australian, I think that’s one of the most important takeaway aspects of the book.

Absolutely, the family is really interesting because they’re supposed to be the family, the people you know most about but in so many ways, and I think this is the case for a lot of people, but you never really get the opportunity to get a full account of some of those stories until you start writing about them, or until you start asking certain questions, like exactly what did happen. I’d grown up in a house that was really full of stuff, and it wasn’t until I was a bit older as a child that I thought, “None of this stuff is ours. How did it actually get here?” That turned into me writing this story about my extended family being deported, this incredibly traumatic time for my family in the mid ‘80s and I only would have been 4 years old and pretty oblivious to what happened.

I think writing that story was really important because it gave me a sense that I do come from pretty amazing stock, really resilient people who were really willing to take a bet on this country. My parents were lucky they got to stay, that they became citizens. I think that’s the case for a lot of children with migrant parents, as well. You really want to try hard because you constantly, whether you’re aware of it or not, you are constantly reminded of how much they went through just to come here and what they had to give up to come here. I think that story is probably an illustration of that.

Is there a story in the book that you’re most proud of, or a chapter in the book that you favor?

Is there a story in the book that you’re most proud of, or a chapter in the book that you favor?

I really like the story about my dad, and his dad. It starts off with me not knowing how to buy my dad presents because he works 24/7 and he doesn’t have any pastimes because he works so hard. That of course leads into the story of his dad as well and he’s not someone I grew up with. He died way before I was born. He died when my dad was a kid, so finding out that story was really important to me, getting a sense of who my dad was when he was young, as well, was really important to me. That’s probably one story I’m proud of because it’s the kind of story that none of my siblings had unearthed either, and I hadn’t really investigated it until I started writing this book.

This really interesting process of “Dad, tell me what happened”; sometimes those stories aren’t told until you ask those questions. I’m not sure if it’s pride but I’m really glad and relieved that I got that story out of dad. He’s not the biggest storyteller. He’s not about to tell you stories for the sake of it. He’s a very practical guy but when you ask him questions, all these stories come out and that story wasn’t even half of it. It gave me a much clearer sense of who dad was, and what drove him to the guy he is now. All these interesting processes of finding out what were you parents like when they were your age; you sort of forget that your parents were your age. That was a really good, fun process.

Another topic I found interesting was how you didn’t gloss over the divorce. You told time and time how unhappy your parents were. It was obviously a very frightening thing as a child but you kind of accepted it.

Divorce is interesting. One of the things about this book is I think I’ve written it from a point of pride. I’m proud my family went through this incredibly difficult time of my parents splitting up and came out of it relatively okay. For all intents and purposes, we still like each other, probably not my parents, but everyone else likes each other. I think divorce is one of those things that, especially in the Chinese community, it’s not really talked about.

You mentioned that in the dialogue, that the Asian community came and spoke to the kids.

They totally feel it’s their right to come in and give their opinions. I always thought that was a bit strange. It’s not until you grow up that you realise how hard it would’ve been for your parents, like you always feel like “this is such a miserable time for me” when you’re a child who comes from divorced parents and the broken family. But, it’s only when you become an adult that you start to realise how difficult it would’ve been for them.

My mom is a tiny woman. She had 5 kids, all school aged at that stage and she decided to say no to my dad, break off the marriage, and raise his children on her own. I don’t even know where that impulse would have come from. I don’t know how she could’ve brought yourself to that point to say, “I’m brave enough to do this”.

I think writing the book has given me an opportunity to look back on that as well. I think writing the book has also given me the opportunity to see some of the humour in it, as well. When you’re in that situation it’s pretty grim. But in hindsight it’s sort of hilarious as well.

There is this one story that I really like and it’s all about my dad taking us on his weekends, during the divorce. On paper, shared custody is supposed to be a pretty clean thing. Maybe the mother gets you Monday through Friday and the dad gets you every weekend or second weekend. It’s quite quarantined how everything works.

The reality of it is completely different and it’s wild. We grew up in the Sunshine Coast, and of course the Sunshine Coast has these terrible theme parks, totally completely opposite to the Gold Coast, so Sunshine Coast – we went to things like the deer sanctuary and Superbee for my dad’s weekends, and Nostalgia Town as well.

I went to Nostalgia Town as a child, too. I thought it was kind of cool at the time, but in retrospect, maybe it wasn’t…

It was quite strange wasn’t it? You can’t help but laugh. My dad tried to take us to these places to show us a good time, but they were sort of lame. He wanted to have time with the kids but my mum insisted on going with him. We went to these places that were supposed to be fun, but smelled like urine. It’s sort of this tragic comedy, really. But at the time it just seems tragic. With retrospect you realise it’s actually a really funny piece. I guess that’s where most of the book comes from, black humour. I dig tragic comedy.

I know the press release mentioned David Sedaris, so he’s obviously one of your influences. You did mention that when we first met. You described it as a ‘David Sedaris kind of book’. Are there any other kind of humour writers you enjoy?

Sedaris is probably the main one. I remember reading him for the first time and thinking “this guy is pretty awesome,” and I identified with him because similarly he came from a big, sprawling family, had a migrant parent, gay, and had that perspective on grim humour that I quite liked.

Augustine Burroughs probably does that, as well, Running with Scissors. I also like people who write good, straight personal essays, who aren’t necessarily in it for laughs as well, like Joan Didion and Zadie Smith. Michael Chabon’s essays, as well. I’ve read a lot of fiction, but I really like when people just write about themselves and I get to know them, probably, as people as well. I like that sense of intimacy. Those are probably the big guys for me.

You’ve been tagged as a comedy writer, or a humour writer. There is some kind of danger associated with that because comedy is subjective. As soon as I started reading… for starters, I could picture your voice as I read it because I’ve met you, obviously. I could picture your deep, baritone voice. That made it funny to me, but then, your humour appeals to me.

It’s not going to appeal to everyone.

It’s not going to appeal to everyone.

Maybe it’s a generational thing.

I’ve already heard from various people that they really like the book but they also couple it with “It’s not going to be for everyone, is it Benjamin?” It’s a bit vulgar and crass but to be honest, that’s how my family is as well. My family often claims that I corrupted them with how disgusting I am, but when I look back into the family archives, and memories of what people were saying at the time, that’s the family. That’s actually the family dynamic, to be quite crass.

The comedy writer tag is dangerous because I think anything that’s considered as comedy is dangerous as inherent failure associated with comedy because not everyone has the same sense of humour. The task of comedy is to make people laugh. You’re not going to make everyone laugh so I think this book is for a very specific audience. That audience probably has some familiarity with dysfunction, to some extent, with their own family. Maybe our younger audience don’t mind a bit of vulgarity and crassness as well. If you get all that you’ll probably like my family. You’ll probably like the book because it’s about my family.

I really liked the chapter about how you met Scott at the end. That was really touching.

Yeah, I wasn’t sure if I was going to write that because you don’t want to write too earnestly about love. Of course, throughout that story, because that’s one story of a few stories in that section, of course I throw in some fart jokes as well. I think that story is sort of important to be in there because growing up gay, it’s still sort of a big deal, and no one was open about it when we went to school, as well. There is always this arrested development involved, especially if you’re someone of my age. I’m in my late 20’s now. You only start finding love a little bit after everyone else, as well.

It’s funny, I interviewed the former Justice of the High Court, Michael Kirby, the other day for Frankie and he was talking about how he didn’t find love or even start looking for it until he was in his late 20’s, early 30’s. There was this whole gap in his life where he didn’t look for love. I hope that a story like that, some young homo might read it and think, “That’s cool, and I might find my own partner one day.” You aren’t particularly vocal about how you are at that young age because you’re vulnerable. That really cuts off your chances in finding someone you might want to be with as well.

Certainly in the book, there is that whole section where I’m 12 years old and already wondering whether I’m going to die alone, that whole fear, crazy things for a 12-year old to be thinking about but that’s the type of kid that I was, completely neurotic. If I was a young teen and I read this book at that young age, and nothing like that existed for me at that age, I think I would get something positive out of it. At least as the writer, I hope young people would.

You mentioned in the book how your fellow high school students didn’t suspect that you were gay. To then, there was no way that you could be both a racial minority and gay.

It scrambled their radar. It scrambled up everyone’s sonar.

You were invisible to them.

Totally, but I think a lot of the people who read my work, like Frankie readers especially, they’re probably in their late teens and their generation sort of has its shit together. I don’t think we necessarily did.

The book kind of goes through the full range of emotions. I just realised that, at the end, when you were speaking about how you were despairing that you might be alone for your whole life, to finding someone; to being unhappy with the family situation, to that breakup happening and people being happier; you kind of nailed the full range of emotions, I think.

I like that. I never really thought about it that way but it probably makes sense, as well. My parents’ divorce started when I graduated from primary school, and only really ended when I graduated from high school. I had my whole teen years just smothered by these feelings of tension and not wanting to belong to this family at all. I don’t think everything is solved, necessarily, at all, but I do feel like it’s only at this stage of my life that I’m quite happy to be a part of my family. I’m quite happy, proud to be a part of this shambolic, odd family.

And when other people read my work, one of the loveliest things that people say is “Your family is so awesome, I wish I could have been raised in that family.” The 17-year old side of me thinks “What the hell are you talking about? You would not have wanted to belong to my family at all” but I can sort of see in another sense that my family is sort of strong and funny people and nowadays, especially, I enjoy their company immensely. It takes a while. It’s taken a while at least, but I like how you sort of described it as starts in one place and ends in another. That’s probably the chronology of the book, as well; starting in one part of my childhood and ends in a more positive time.

The book ends with the destruction of the house.

Which hasn’t happened yet.

Oh, that was the one creative license that you took?

It hasn’t happened yet. I speculate on what’s going to happen. That’s in the process of happening now. I think it’s going to be incredibly traumatic. I never moved as a kid. I have a lot of friends who say their whole childhood was defined by moving from house to house, from school to school, and they never got that sense of security. I was sort of the opposite. We never moved.

I was born into a house and when I go visit my mum that’s still the house that I go back to. It is the “childhood home”. I certainly don’t want to destroy it. If I dream about a house, it will be that house. It’s a really old house now. It’s sort of falling apart by the seams and I think there’s going to be some total sense of devastation when it’s gone because I’m coming up to my late 20’s, 30’s now and to know that’s been the one house, your family house. Those are where your roots are; I think it’s going to be sad to see it go. It’s a long process to make it all happen.

I like how in the end you acknowledged your editors for encouraging you to write along the way. I wonder how much your journalistic tendencies from your freelance work informs how you wrote the book itself.

Journalism skills came in handy for some of the stories. Interviewing is an obvious one, but also stuff like… It could have been one of those montages from a detective film: microfilm blurring over your face, zooming in and printing out copies.

That was really interesting and that’s not just from journalism but because I’ve studied for so long, as well, that I know how to use all that stuff, and get into the archives. It wasn’t until I did that that I realised how big news that was. Obviously, my family being deported was big news in my family and it’s a pretty defining era in our history, but it was sort of defining to the whole community, the whole Sunshine Coast community at that stage. It was front-page news for probably a few weeks, and continued to be news for two months, broadcast news, and newspapers. It was really interesting and it was interesting knowing – listening how the tone of reporting those issues changed as well.

This was in the mid ‘80s where my extended family got deported and most of the coverage was incredibly supportive of my family, whereas I think now if that story happened, I’m not sure it would be that supportive of a migrant family who had stayed here illegally and were now being deported; most of the editorials that were written were in favour of them staying. Most of the headlines were in favour of them staying, as well. My baby cousin was born and she was born a citizen but her parents were illegal immigrants. Everyone really rallied for that loophole to be taken advantage of where hopefully her parents could stay because of her. It was really fascinating reading my family story as news. I’m trying to think if there are any other ways journalism came into it. Probably those are the main things, skills wise, at least.

I hear you’re going to South-east Asia for your next book project.

That’s right. A completely different book project, the first book is all about myself and my family. The second book is a travelogue. In another way, the second book will sort of be about myself. I’ll tell you what the concept is.

The concept is traveling throughout Southeast Asia and profiling different gay, lesbian, transsexual, queer communities. One of the fundamental questions at the heart of the book is; here I am as a young, gay Asian dude in a relatively tolerant society of queer rights, when it comes to the world at large; we’re relatively good here in Australia. I’m going to be traveling throughout China, Thailand, Japan, India, Nepal, Singapore, some regions where homosexual conduct is illegal, and asking what would have happened if I’d been born anywhere close to where my folks are actually from; who would my life be different.

In one sense, the second book is going to be quite different in tone and subject matter, but in another way it’s still asking some fundamental questions about what would life have been like for me in a different place. I guess that’s what a lot of children of migrants ask of themselves as well; what would my life have been like if I’d been raised as my parents had been raised. I’m looking forward to researching that.

In one sense, the second book is going to be quite different in tone and subject matter, but in another way it’s still asking some fundamental questions about what would life have been like for me in a different place. I guess that’s what a lot of children of migrants ask of themselves as well; what would my life have been like if I’d been raised as my parents had been raised. I’m looking forward to researching that.

Are you keeping a diary on that trip?

I will be. I’ll be more disciplined this time. I think there are reasons to, as well. I’m about to attend the world’s biggest transsexual beauty pageant in Thailand. I think keeping a diary for that would be a good idea. I’m looking forward to it.

Thanks for your time, Benjamin.

++

More Benjamin Law on his website and Twitter. Go buy The Family Law via independent retailers like Avid Reader [Bris], Readings [Melb] or Glee Books [Syd].