The Weekend Australian album reviews, September 2012: The Presets, We All Want To, Sugar Army

Three album reviews for The Weekend Australian, published in September. The first is a feature review of 490 words; the other two are regular 260-worders.

++

Four years between albums is plenty of time for younger competitors to snatch the crown from Australia’s electronic music kings.

The Presets’ top spot was earned after 2008’s Apocalypso, which spawned multi-platinum sales, ARIA awards and one world-conquering single in ‘My People’.

Now in their mid-30s, Sydney-based Julian Hamilton and Kim Moyes have exchanged nightclubs for parenthood. One may assume they’ve lost touch with the culture that spawned this synth-and-drums duo and their stunning 2005 debut, Beams.

All doubts are vanquished within the first few bars of the first single, ‘Youth in Trouble’. The six-minute track is built on an insistent bass pattern, on top of which Hamilton – in typical piss-taking vocal style – parodies the media-led hand-wringing on behalf of Australian parents.

“Up out all night in bright-lit wonderland . . . With a music taste abominable / Man, I’m worried sick for youth in trouble.” The layered irony is wonderful: moments later, the track fills with the kind of electronic noise and subterranean bass that’d piss off parents when played loud. As it should be.

This track is a departure from the clear, concise vocal hooks that have characterised the Presets’ past hits. It’s a perfect album opener because Pacifica bears little resemblance to their previous two releases. These 10 tracks are more electronica than dance music; to use an obvious party-drug analogy, it’s more 5am comedown than 1am peak. At first, Pacifica‘s incongruity is a tough pill to swallow.

The lack of obvious singles is troubling — the sea-shanty-like ‘Ghosts’ is the most accessible track here — as is the apparent dearth of vocal and melodic hooks. This jars with popular understanding of who the Presets are, and what they represent. It takes me about six listens to accept this record for what it is, not what it could have been if they had continued to follow their own songwriting formula. Impatient, dismissive fans will miss out on the Presets’ most accomplished and mature album yet.

Pacifica sees the pair bower-birding from a wide range of aural sources: shades of dance titans Underworld and Sonicanimation are occasionally detectable, as well as more modern electronic acts such as Crystal Castles and the Knife.

The latter influence is particularly strong in track seven, ‘Adults Only’, which sees Hamilton pitch-shifting his vocals to a deep tone, as if trying to obscure his identity. This song is the album’s emotional and artistic peak; a punishing acid-house pastiche led by stuttering, hornet-swarm synths.

Inspired by John Birmingham’s Leviathan, Hamilton’s dark lyrics take in Sydney’s murderous past and uncertain future: “Children don’t you know that we’re living in a city that’s built on bones?” he sings in the chorus; later, he mentions frail old ladies dying afraid and alone while surrounded by yuppies, small bars and coke.

Ultimately, Pacifica is the sound of two men who understand Australian pop culture better than anyone. ‘Zeitgeist’ is a dirty word, but there’s no doubt the Presets have produced a record that sounds simultaneously of-the-moment and futuristic. The crown remains intact.

LABEL: Modular/UMA

RATING: 4 stars

++

We All Want To – Come Up Invisible

This is a messy album in the best way possible. The music created by Brisbane four-piece We All Want To swings back and forth between charming indie pop and rock with jagged edges.

Led by a pair of singer-guitarists in Tim Steward – who also fronted 90s-era Brisbane noise-pop act Screamfeeder — and Skye Staniford, the interplay between the two is the chief highlight here. Both are accomplished writers with a knack for clever wordplay and memorable melodies.

They opt for some artistic decisions that simply wouldn’t work in less capable hands – like opening the album with a sprawling, seven-minute track that features an off-key recorder solo — yet these four pull off such curiosities with style. The band’s self-titled debut, released in 2010, was a solid set containing a pair of stand-outs in ‘Japan’ and ‘Back to the Car’.

It’s a similar story here: special mentions belong to Steward’s compelling, life-spanning narrative in ‘Where Sleeping Ends’; and ‘Shine’ by Staniford, which begins with subdued instrumentation and ends with a whirlwind of beautiful harmonies. There are no ongoing lyrical themes to speak of, nor is there much sense of cohesion between these 11 tracks, but these absences don’t matter: there’s not a weak track here. This collection is accomplished, unpretentious and unassuming.

We All Want To is no spring chicken. Steward has been playing live for more than two decades and this is the 11th album he has been involved in. Come Up Invisible is a nod to the virtues of banking on earned musical wisdom and experience.

LABEL: Plus One Records

RATING: 3 ½ stars

++

Through change comes artistic progress. On its second album, Perth-based rock act Sugar Army has streamlined the sound out of necessity: the band’s bassist joined fellow Perth group Birds of Tokyo, reducing the quartet to a trio.

Yet this departure has helped to hone Summertime Heavy into a set of compact, driving rock songs. Sugar Army’s 2009 debut, The Parallels Amongst Ourselves, was memorable but a touch overlong; half the tracks were great, the others less so.

Here, the band has scaled back the atmospheric production in favour of muscular songwriting, and the results are impressive. Sugar Army’s sound evokes Los Angeles act Silversun Pickups in that the guitar phrasing, bass lines and drumbeats are all independently interesting.

This clever musical interplay, coupled with Patrick Mclaughlin’s distinctive voice, ensures they’re a near-perfect unit. Mclaughlin has a unique turn of phrase, too: “Once the mind’s made up / Nothing comes in, and nobody gets out”, he sings in ‘Small Town Charm’, which nails the realities of some regional mentalities.

In standout album closer ‘Brazen Young’ he continues his fascination with female-led narratives first noted on their debut. These are lean, well-written songs delivered forcefully and urgently.

The band is versatile, too: the title track is built around a pretty acoustic guitar progression and a chanted motif (“Summertime heavy is taking its toll”), while the appearance of a wood block in ‘Hearts Content’ is both unexpected and welcome. As the Go-Betweens’ Robert Forster has said, the three-piece band is the purest form of rock ‘n’ roll expression. That holds true here.

LABEL: Permanent Records

RATING: 3 ½ stars

Four albums into a career that blossomed with the release of second LP Granddance in 2006, Sydney quintet Dappled Cities here present their most accomplished collection. Granddance brought the band into the national consciousness via a string of outstanding singles; Lake Air is a complete work, one so good it deserves to take Dappled Cities much further.

Four albums into a career that blossomed with the release of second LP Granddance in 2006, Sydney quintet Dappled Cities here present their most accomplished collection. Granddance brought the band into the national consciousness via a string of outstanding singles; Lake Air is a complete work, one so good it deserves to take Dappled Cities much further. I didn’t know this until I read The Boy Who Loved Apples, in which first-time author Amanda Webster takes on twin challenges: to write a confessional account of the most difficult time of her life and to educate readers about the complexities of an illness few understand intimately, especially as it applies to boys. She succeeds on both counts.

I didn’t know this until I read The Boy Who Loved Apples, in which first-time author Amanda Webster takes on twin challenges: to write a confessional account of the most difficult time of her life and to educate readers about the complexities of an illness few understand intimately, especially as it applies to boys. She succeeds on both counts. The young man at the heart of this band has been worth watching since he emerged in late 2009. Jonathan Boulet’s self-titled, self-recorded, self-produced debut was bursting at the seams with ideas (he played all the instruments and sang, too.) Boulet’s songwriting didn’t always hit the mark, but he certainly showed promise.

The young man at the heart of this band has been worth watching since he emerged in late 2009. Jonathan Boulet’s self-titled, self-recorded, self-produced debut was bursting at the seams with ideas (he played all the instruments and sang, too.) Boulet’s songwriting didn’t always hit the mark, but he certainly showed promise. In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as  Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling. Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh.

Where many rock bands fail, Silversun Pickups succeed: through effective use of space, volume, melody and harmony, this Los Angeles quartet conjures unique emotions within the listener that make the timeworn combination of guitars, bass, drums and vocals seem fresh. These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011.

These 10 sparsely adorned songs represent a significant shift for Perth-based songwriter Joe McKee, who fronted the West Australian quartet Snowman for eight years until their amicable split in 2011. What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music.

What we now take for granted once existed only on the fringes of popular music. Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam.

Too often, young Australian rappers fall into the same lyrical pitfall: with little life experience to speak of, they instead take the dubious advice of “write what you know” too literally by couching their artistry in recording alcohol and drug-fuelled tales ad nauseam. By combining the ethos and aesthetics of punk-rock and electronica with hip-hop, Californian trio Death Grips have established an entirely unique sound.

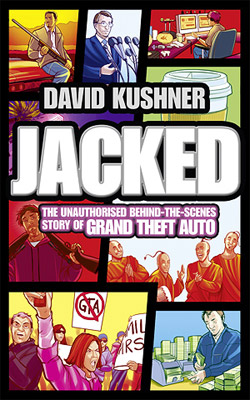

By combining the ethos and aesthetics of punk-rock and electronica with hip-hop, Californian trio Death Grips have established an entirely unique sound. ‘GRAND Theft Auto revolutionised an industry, defined one generation, and pissed off another, transforming a medium long thought of as kids’ stuff into something culturally relevant, darkly funny, and wildly free,” David Kushner writes in his second video game-themed book.

‘GRAND Theft Auto revolutionised an industry, defined one generation, and pissed off another, transforming a medium long thought of as kids’ stuff into something culturally relevant, darkly funny, and wildly free,” David Kushner writes in his second video game-themed book.