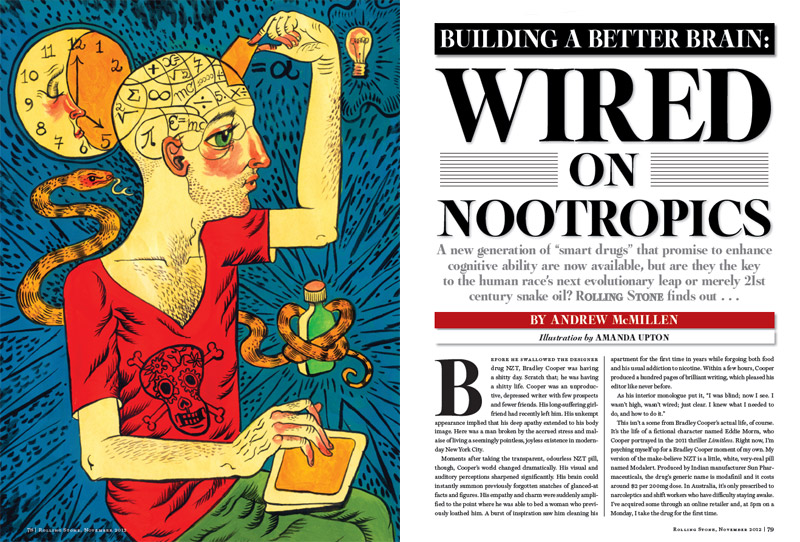

Building A Better Brain: Wired on Nootropics

By Andrew McMillen / Illustration by Amanda Upton

A new generation of “smart drugs” that promise to enhance cognitive ability are now available, but are they the key to the human race’s next evolutionary leap or merely 21st century snake oil? Rolling Stone finds out…

Before he swallowed the designer drug NZT, Bradley Cooper was having a shitty day. Scratch that; he was having a shitty life. Cooper was an unproductive, depressed writer with few prospects and fewer friends. His long-suffering girlfriend had recently left him. His unkempt appearance implied that his deep apathy extended to his body image. Here was a man broken by the accrued stress and malaise of living a seemingly pointless, joyless existence in modern day New York City.

Moments after taking the transparent, odourless NZT pill, though, Cooper’s world changed dramatically. His visual and auditory perceptions sharpened significantly. His brain could instantly summon previously forgotten snatches of glanced-at facts and figures. His empathy and charm were suddenly amplified to the point where he was able to bed a woman who previously loathed him. A burst of inspiration saw him cleaning his apartment for the first time in years while forgoing both food and his usual addiction to nicotine. Within a few hours, Cooper produced a hundred pages of brilliant writing, which pleased his editor like never before.

As his interior monologue put it, “I was blind; now I see. I wasn’t high, wasn’t wired; just clear. I knew what I needed to do, and how to do it.”

This isn’t a scene from Bradley Cooper’s actual life, of course. It’s the life of a fictional character named Eddie Morra, which Cooper portrayed in the 2011 thriller Limitless. Right now, I’m psyching myself up for a Bradley Cooper moment of my own. My version of the make-believe NZT is a little, white, very real pill named Modalert. Produced by Indian manufacturer Sun Pharmaceuticals, the drug’s generic name is modafinil and it costs around $2 per 200mg dose. In Australia, it’s only prescribed to narcoleptics and shift workers who have difficulty staying awake. I’ve acquired some through an online retailer and at 5pm on a Monday, I take the drug for the first time.

By 10pm I’m wide awake, and aware that my resting heart-rate is higher than normal. By midnight my mind is racing around like an agitated puppy: “Hey! Here I am! Play with me!” I occupy myself with the normally tedious task of transcribing interviews; when I next look at the clock, it’s 3.30am and I’m finished. I’m washing dishes to take a break from work, when I realise that my randomly chosen soundtrack has taken on an eerie parallel to real life. In the classic Nas track ‘N.Y. State of Mind’, he raps: “I never sleep / ‘Cuz sleep is the cousin of death.”

For as long as I can remember, my answer to that age-old ‘just one wish’ hypothetical has been ‘to never fatigue’. To never need to sleep. To be able to learn, create and achieve more than any regular human being because I’m no longer confined by the boring necessity of a good night’s sleep.

Thanks to modafinil, I’m closer to this long-held dream than ever before. And I feel incredible. Not high, not wired; just clear. The computer in my skull is crunching ones and zeroes while the rest of the world sleeps. I yawn occasionally, but my mind feels focused, at capacity, even as 5am approaches.

It’s a kind of cognitive dissonance I’ve never experienced before; I know I should be feeling fatigued by now, but everything’s still working well. At 8.30am – roughly fifteen hours after taking the drug, which corresponds with its stated half-life – its effects wear off, and fatigue sets in. I take a three-hour nap, then pop another modafinil upon waking. I’m back on the merry-go-round of sleeplessness, and loving it.

Giddy at the near-endless productivity possibilities that I’ve suddenly unlocked, I confess my off-label use of Modalert to a Sun Pharma spokesperson via email in a moment of clarity (or, perhaps, over-earnest honesty). The reply arrives in my inbox a short time later, and I’m briefly quietened by its ominous tone.

“You’ve seen Limitless?” the Indian drug rep replies. “The cost is too much. Please evaluate what you are doing, even for test purposes. Neuronal circuitry is not to be messed with.”

++

Modafinil is the brightest star in a galaxy of drugs and supplements called ‘nootropics’. The word was coined by a Romanian doctor in 1972; in Greek, its definition refers to ‘turning the mind’. More commonly known as ‘smart drugs’ or ‘cognitive enhancers’, nootropics work in one of three ways: by altering the availability of the brain’s supply of neurochemicals; by improving the brain’s oxygen supply; or by stimulating nerve growth.

Smart drugs are not a new concept. Last century, both cocaine and amphetamine were considered to have enhancement potential. As researchers at the University of Queensland wrote in a 2012 paper, “…their use for this purpose was regarded in a wholly positive light. [Cocaine and amphetamine] were seen as safe and effective ‘wonder drugs’ that increased alertness and mental capabilities, thereby allowing users to cope better with the increasing demands of modern life.” These views became unpopular once both substances were found to be addictive: cocaine became a prohibited substance, though amphetamine is still widely prescribed as a treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) under the brand name Adderall.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), Australian drug regulation authority, does not yet recognise nootropics as a class of drug, as “the information available on nootropic products provides a very broad definition.” A TGA spokesperson tells Rolling Stone that they are unable to comment on the matter, as “the issue here is that the definition of nootropics goes from nutritional supplements all the way through to prescription medicines, so depending on what the product is and its claims, it might be considered as listable, a registered complementary medicine, or a registered prescription medicine.”

So regulation is a murky topic, then. But nootropics aren’t illegal, either. Admittedly, taking modafinil off-label is not a smart thing to do. I am not a narcoleptic. I sleep just fine, if begrudgingly. I am a healthy 24 year-old male who exercises regularly and eats well. My recreational drug use is occasional. I’ve never been addicted to anything, and I intend to keep that clean sheet. I would like to be able to concentrate for long periods during the work week, though. I’d like to be able to instantly summon previously forgotten snatches of glanced-at facts. In short, I’d like to be smarter. Who wouldn’t?

In the fictional account of Limitless and its inspiration, a 2001 techno-thriller by Irish author Alan Glynn named The Dark Fields, the universally appealing idea of self-improvement through minimal effort is explored by a guy taking a designer drug to boost his brainpower to superhuman levels. In reality, nootropic enthusiasts claim significant cognitive benefits with few, if any, side effects from taking these supposedly non-addictive, non-toxic substances.

Sounds too good to be true? You bet. With my bullshit detector cranked up to eleven, I’m wading into this contentious field with the goal of separating science from fiction. Are smart drugs the snake oil of the 21st century? Or am I about to become a better man just by taking a bunch of coloured pills?

++

After Eddie Morra tires of writing while under the influence of NZT, he turns his attention to the far more lucrative stock market. When I tire of writing on modafinil, I waste away the night-time hours by shooting terrorists in Counter-Strike: Source online, trawling internet forums, and reading about nootropics.

With a newfound surplus of time arises an interesting dilemma: how to spend it? I chose to alternately work, read, and play games. What if every night was like that, though? What if I had all that time? How soon would I become accustomed to operating on little, or zero, sleep? What would be the side-effects of this for my health, my relationships, my career? Would I become a kinder person? Would parts of my personality become amplified, or atrophy? Obvious productivity gains – or productivity opportunity gains – aside, would less sleep make me a better person?

All Tuesday night, I’m keyed into a writing task with laser-like focus. By sunrise, I’ve produced an article which, at the time, feels like some of my best work yet. (When it’s published online, weeks later, I read it with fresh eyes and I’m pleasantly surprised to find that I still feel the same way.) On Wednesday, I choose to take a break from the drug, but I’m still up until 4am. My sleep cycle has been totally disrupted.

Thursday just feels like a regular day. I’m yawning more than usual, probably due to the sleep debt I’ve incurred this week. But it does feel a little… boring to be operating at this level, rather than on modafinil, where I feel like I’m connecting all of the dots all of the time. I suddenly find myself weighing up the costs and benefits of taking a pill right now. I have nothing in particular that needs to be completed for the remainder of the week, but there’s an internal argument happening: “Being awake is so much more enjoyable than sleeping. Who needs sleep, honestly?”

Thursday just feels like a regular day. I’m yawning more than usual, probably due to the sleep debt I’ve incurred this week. But it does feel a little… boring to be operating at this level, rather than on modafinil, where I feel like I’m connecting all of the dots all of the time. I suddenly find myself weighing up the costs and benefits of taking a pill right now. I have nothing in particular that needs to be completed for the remainder of the week, but there’s an internal argument happening: “Being awake is so much more enjoyable than sleeping. Who needs sleep, honestly?”

I dose another 200mg, and within the hour, I again find myself making connections in music that I’d never previously noticed. The Black Rebel Motorcycle Club song ‘Stop’ aligns with my current mindset: “We don’t know where to stop / I try and I try but I can’t get enough…”

I feel like an outlaw; as though I’m in on a secret to which everyone else is oblivious. I know how to subvert sleep; that knowledge is in the shape of a small white disc containing 200mg of modafinil. I feel as though taking this drug might be one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. I want everyone around me to take it, too, so that we can share our experiences and revel in the euphoria of the unclouded mind.

That night, I drive to and from a rock show. I meet friends and strangers at the venue; as I talk, I feel as though I’m not making sense, and that those around me are acutely aware of this. I feel in control, but my mind is racing faster than my mouth can keep up. I buy one beer and feel a little drunk, but I don’t come close to crashing my car on the drive home. Around 2am, I note that I’ve got an impending feeling of doom going on. Like I’m riding this too far, and it’s about to start doing some serious damage. I turn in at 3.30am on Friday.

My first nootropic odyssey whimpers to a close, after beginning with a giddy bang at 10am on Monday morning. I’ve taken three 200mg doses of modafinil during that time – 5pm Monday, 1pm Tuesday, 2.30pm Thursday – and napped for around 11 hours total. In all, I’ve been awake for 79 out of the last 90 hours.

I arise at midday, refreshed, having effectively reset my debt with one normal sleep. I reflect on how my views toward modafinil have veered between utter devotion to, now, in the cold light of day, a realisation that it’s probably not a good idea to be taking that shit on consecutive days. I was feeling so fucking average the night before. I couldn’t bear the thought of continuing to stay awake. The body and the mind aren’t made for it.

++

Next, I purchase some homemade nootropics from a vendor named Tryptamine on Silk Road (SR), an anonymous online market where illicit drugs are purchased with virtual currency and sent through the international postal system. Tryptamine’s vendor profile states, “I am a biologist who develops nutritional supplements to improve your health, sleep, and cognition. I use only natural or orthomolecular ingredients, and no adverse effects have been reported from my products.”

Tryptamine makes and sells three nootropics. I order two 24-pill bottles of MindFood (“designed to optimize brain function, protect against stress- and drug-induced neurotoxicity, prevent/alleviate hangovers, and reverse brain aging,” among other alleged effects), and ChillPill (“designed to promote relaxation, attenuate stress, calm excess brain activity, enhance mood, and promote dreaming”). The seller kindly includes a bonus five-pill sampler of ThinkDeep (“designed to stimulate brain metabolism and glucose uptake, improve memory formation/recall, expand attention span, prevent mental fatigue and enhance blood flow”), too.

The total cost is around AUD$100. As I pay this seemingly exorbitant amount, I’m reminded of that old aphorism about fools and their money. The package lands in my mailbox via the state of New York around two weeks later. The pills are brightly coloured and strong-smelling. I try all three nootropics in isolation, one or two at a time, on different days.

After swallowing a ThinkDeep for the first time, I realise that I just took an anonymous black and red pill created by an anonymous internet seller who claims to be a biologist. They’ve got a 100% feedback record from over 400 transactions on SR, which counts as a sort of social proof, but still: bad things could happen to me after taking this pill, and the person responsible would never be caught out. (Tryptamine denied Rolling Stone’s request to verify his/her identity, or scientific credentials. “Whatever image you have in your mind’s eye from reading this, that’s how I look,” the seller wrote.)

“Silk Road allows me to sell my products anonymously, and provides me with hundreds of thousands of potential customers who already take pills that aren’t made by pharmaceutical companies,” Tryptamine tells me. “On the other hand, it is a bit off-putting to see my products listed beside bags of heroin.”

As it turns out, ThinkDeep doesn’t do much for me, even on another day when I double-dose. In fact, the only significant effect I notice from these three products is when one dose of MindFood eradicates a hangover much faster than my regular methods of paracetamol and/or ibuprofen. Perhaps ThinkDeep and ChillPill are so subtle that I don’t notice their effects; perhaps they don’t work at all. Potential hangover cure aside, it’s difficult to recommend these products for cognitive enhancement purposes.

At the other end of the nootropic spectrum, far from secretive biologists and solo recipe-tweaking, is an Austin, Texas-based company named Onnit. Their flagship product is named Alpha Brain, which is slickly marketed as a “complete balanced nootropic”. Their biggest public advocate is the comedian, podcaster and former host of Fear Factor, Joe Rogan; they also have a few World Series of Poker players hyping the product on their website. I ordered a 30-pill bottle of Alpha Brain for around $40.

Each green pill includes small amounts of eleven impressive-sounding substances, from vitamin B6 and vinpocetine, to L-theanine and oat straw. The serving size on the label suggests two pills at a time; as I discover, taking one does nothing. With two Alpha Brain pills circulating in my system, though, I feel an overall mood elevation and a heightened ability to concentrate on tasks at hand: reading, writing, researching. These effects last for between four to six hours.

Alpha Brain worked for me, but it also feels like a triumph of marketing, too. As there are no clear estimates about the financial side of the nootropics industry, I ask Onnit CEO Aubrey Marcus whether it’s a lucrative field. “Absolutely,” he replies, though he won’t comment on Onnit’s annual turnover. “It’s something that everybody can benefit from. Whenever you tap into something [like that], there’s ample opportunity to make good money.” Marcus says that Alpha Brain has been purchased by around 45,000 customers across the world since launching last year. The company currently employs 13 full-time staff.

He acknowledges that nutritional supplement manufacturers are met with their fair share of critics. “The pharmaceutical industry has done a good job of telling people that synthetic drugs are the only things that have an effect on the body. There are plenty who’ve never tried our products who’ll swear that they’re snake oil,” Marcus laughs. “We encounter that, and we just do our best to show as much research behind all the ingredients that we have.” He mentions that Onnit are intending to commission a double-blind clinical study on the effects of Alpha Brain, which he believes “will go a long way to silence the critics.”

++

Perhaps nootropics aren’t a mainstream concept yet because the people most enthusiastic about their potential benefits are all scientists, marketers out to make a buck, ‘body hackers’, and other weirdoes. There are few ‘normals’ taking these drugs and supplements on a daily basis, so it all looks too strange and confronting for outsiders to try. As a society, we’re taught by our peers and the media that if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.

There’s also the possibility that nootropics will never become mainstream because their effectiveness is difficult to qualitatively measure, or alternatively, they don’t work at all. In this regard, Australian researchers are world-class sceptics of cognitive enhancement. When I visit the University Of Queensland’s Centre for Clinical Research (UQCCR) in Brisbane, I’m greeted by Professor Wayne Hall, who was first published on this topic in 2004. His essay, which appeared in a European biology journal, was entitled “Feeling ‘better than well’: Can our experiences with psychoactive drugs help us to meet the challenges of neuroenhancement methods?”

Hall has studied addiction and drug use for over 20 years. “There’s been a fair amount of enthusiasm for cognitive enhancement [in scientific circles], but it hasn’t looked critically at the evidence on how common this behaviour is,” he says. The professor and his peers argue for “taking a step back, and not getting too excited or encourage unwittingly lots of people to experiment with stimulant drugs for the wrong sorts of reasons”.

“If you look at the lab studies that have been done on whether these drugs [work], the effects – insofar as there are some – are fairly modest and short-lived,” Hall says. “To be jumping from that, to saying it’s good idea for people to be using these drugs regularly to enhance their cognitive performance, is a bit of a long bow.”

Dr Bradley Partridge is another UQCCR academic who specialises in investigating “the use of pharmaceuticals by healthy people to enhance their cognition”. I bring along my bottles of Alpha Brain and Tryptamine’s homemade nootropics for him to cast a critical eye over. “I have never used any of these things,” Partridge says. He peers at the labels with bemusement. “And I’ve never heard of most of these ingredients.”

He places the bottles back on the table. “The thing is, a lot of these supplements are touted as being ‘all natural’, and for some people, that implies that they’re perhaps safe. But it’s very hard to evaluate exactly what’s in it. Aside from safety, where’s the evidence that they actually work for their stated purpose?”

“There’s no scientific literature on some of this stuff; for others, the results are very mixed. Also, there might be a really strong placebo effect.” He holds up the Alpha Brain bottle, which mentions ‘enhancing mental performance’ in its marketing copy. “You take this and you do an exam; maybe simply taking something makes you feel like you ought to be doing better, and maybe you convince yourself that you’re getting some effect.”

Hall and Partridge co-authored a study which analysed media reports on “smart drugs”. They found that 95 per cent of media reports mentioned some benefit of taking a drug like Adderall, Ritalin or modafinil, while only 58 per cent mentioned side effects. “I tend to be very cautious about this stuff,” Partridge says. “I don’t like to see this getting portrayed as a widespread phenomenon, as a fantastic thing, that it works, that there are no side effects. That runs the risk of encouraging people who hadn’t thought about it to take it up, which could cause problems for people.”

I offer to leave some of my nootropics with Dr Partridge for him to conduct his own research; he laughs, and politely declines.

++

Underscoring this entire discussion is the threat of one-upmanship. If I’m taking these drugs and they markedly improve my performance, am I nothing but a filthy nootropic cheater? To address this question, I spoke with Dave Asprey, who has used modafinil constantly for eight years and describes himself on Twitter as a “New York Times-published Silicon Valley entrepreneur/executive/angel who hacked his own biology to gain an unfair advantage in business and life.”

Asprey has a prescription for the drug, after a brain scan showed a lack of blood flow at the front of his brain – a common symptom of attention deficit disorder (ADD), he says. “Modafinil is actually used commonly as a treatment for ADD,” he tells me. “It’s an off-label use, but it’s accepted; it’s even reimbursable by some insurance companies.”

Asprey takes modafinil most workdays, upon waking. “It’s not like it’s a great secret out there, it’s just that people don’t talk about it because there’s some feel as though it’s ‘cheating’,” he says. “My perspective is different: if you eat healthy food, then you’re also ‘cheating’, because that impacts brain function. Surprisingly, the only people who’ve ever given me shit about taking modafinil are like, ‘but how do you know it’s not hurting you?’ I’m a bio-hacker; I’ve done all sorts of strange things to my body and mind in the interests of anti-aging, health and performance. I look at my body as part of my support system.’”

Asprey says that he considers modafinil to be on the healthier spectrum of drugs. He’s also a fan of aniracetam, a fat soluble version of piracetam, which itself was the first-ever nootropic discovered in 1964. “It’s longer lasting [than piracetam],” Asprey says. “I recommend it as a basic biohack. I’ve been using it for a very long time.”

Though Asprey has never met anyone who bluntly considers nootropics to be bullshit, he hears another argument reasonably often – and he has a clever rebuttal ready. “People say, ‘[nootropics] are evil, because if you take them, then everyone else will have to take them!’ I don’t think that’s a very fair argument, because from that perspective, fire is evil. Back when there were two cavemen, and one had a fire, the other said, ‘you can’t use fire, that’s unfair!’ Well, we know who evolved.”

++

Whether or not I’m qualitatively smarter after experimenting with nootropics for this story is difficult to measure. I feel slightly wiser, and more aware of the limitations of both mind and body after that week of bingeing on modafinil. I certainly appreciate the restorative value of sleep better than ever before, after staying awake for the best part of a full work-week. I found that Alpha Brain is useful for focusing for a few hours, but considering that a two-week supply costs $40, it seems a touch on the expensive side.

I did order a few dozen additional pills of modafinil, but I intend to use these only when emergency deadlines necessitate long hours. (I’ve read it’s good for combating the effects of jet lag, though, so perhaps I’ll try it on my next international flight.) Ultimately, the nootropic I found most useful – and intend to continue using regularly – is aniracetam, which Dave Asprey told me about. Its mind-sharpening effects are subtler than Alpha Brain, but it’s much cheaper – around $40 for a month’s supply if purchased online – and its effects taper off much more pleasantly than Alpha Brain’s comparatively sudden drop-off in concentration and energy levels.

Late one night while researching this story, modafinil coursing through my body, I watched Limitless for the second time. It’s not a brilliant film, but it’s entertaining and thought-provoking enough to make the viewer consider seeking out smart pills of their own. It’s easy to see why the nootropic industry’s shadier sellers have attempted to draw parallels between their products and the fictional substance of NZT. After viewing the film, I contacted Alan Glynn, the author behind the 2001 techno-thriller The Dark Fields, which Limitless was based on, via email.

“The original idea of NZT – called MDT-48 in my book – came from the idea of human perfectibility, of ‘the three wishes’, of the chance to re-invent yourself, of the shortcut to health and happiness,” Glynn tells me. “This is why the diet and self-help industries are so huge. Hold out a promise like that and people will respond. The fact that most of these products and therapies don’t work, or are bogus, doesn’t seem to matter. The real magic here, the real dark art, is marketing. I think that if nootropics ever go mainstream, they’ll be fodder for the marketing industry.”

“The original idea of NZT – called MDT-48 in my book – came from the idea of human perfectibility, of ‘the three wishes’, of the chance to re-invent yourself, of the shortcut to health and happiness,” Glynn tells me. “This is why the diet and self-help industries are so huge. Hold out a promise like that and people will respond. The fact that most of these products and therapies don’t work, or are bogus, doesn’t seem to matter. The real magic here, the real dark art, is marketing. I think that if nootropics ever go mainstream, they’ll be fodder for the marketing industry.”

I send Glynn a link to the Alpha Brain website and mention that I’ve been taking it while researching this story. “Look, I’m just as much of a sucker as anyone else and when I look at that website, I’m going like, ‘Woah, gimme some of THAT!’” he replies. “And I’m actually seriously considering ordering some. So, from a marketing point of view, I’d say it’s a total success. It’s shiny, professional-looking and stuffed full of ‘the science bit’.”

“But it’s the massaging of the science bit that is the marketer’s real dark art. The truth is, I couldn’t argue with someone who can talk about ‘GPC choline’ and ‘neurotransmitter precursors’. My instinct is that it’s all bullshit… On the other hand. I don’t know. Have you taken Alpha Brain? Does it work?”

I reply in the affirmative, and describe my findings in some detail. Alan Glynn, author of the book that inspired the movie that inspired me to write this story in the first place, writes me back immediately: “That’s interesting indeed. I’ve ordered some Alpha Brain, and I’ve just got an email to say it’s been dispatched. I’ll report back to you – in the interests of science, of course.”

Note: At no point should any of the products mentioned in this article be ingested without first consulting a health professional. An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified Ritalin as an amphetamine; it belongs to the methylphenidate class of stimulants.

“The original idea of NZT – called MDT-48 in my book – came from the idea of human perfectibility, of ‘the three wishes’, of the chance to re-invent yourself, of the shortcut to health and happiness,” Glynn tells me. “This is why the diet and self-help industries are so huge. Hold out a promise like that and people will respond. The fact that most of these products and therapies don’t work, or are bogus, doesn’t seem to matter. The real magic here, the real dark art, is marketing. I think that if nootropics ever go mainstream, they’ll be fodder for the marketing industry.”

“The original idea of NZT – called MDT-48 in my book – came from the idea of human perfectibility, of ‘the three wishes’, of the chance to re-invent yourself, of the shortcut to health and happiness,” Glynn tells me. “This is why the diet and self-help industries are so huge. Hold out a promise like that and people will respond. The fact that most of these products and therapies don’t work, or are bogus, doesn’t seem to matter. The real magic here, the real dark art, is marketing. I think that if nootropics ever go mainstream, they’ll be fodder for the marketing industry.” Play games. Read books. Watch movies. Understand your world, so that when you’ve learned some hands-on, practical skills, you have ideas to make new, exciting forms of games. Generate your own enthusiasm, and your own, new industry. Don’t go and be a little worker; go and make your own world. I think games are just beautiful. Design is powerful. Game design is utterly powerful. You’re playing with culture and philosophy and fun and image and audio; the whole kit and caboodle. Don’t just think about making new forms; think about pushing the boundaries with it.

Play games. Read books. Watch movies. Understand your world, so that when you’ve learned some hands-on, practical skills, you have ideas to make new, exciting forms of games. Generate your own enthusiasm, and your own, new industry. Don’t go and be a little worker; go and make your own world. I think games are just beautiful. Design is powerful. Game design is utterly powerful. You’re playing with culture and philosophy and fun and image and audio; the whole kit and caboodle. Don’t just think about making new forms; think about pushing the boundaries with it. One of the big things we look for when we’re interviewing people is their portfolio. Whether it be as an artist showing your work, or a programmer and having a playable game; that just puts you so far ahead of other people when you’re applying for a job. And even a designer, if you have a little walkthrough video. One of the guys we hired at Krome for Ty the Tasmanian Tiger 2 – Rob Davis, a graduate, who’s now working at Microsoft Games Studios in Seattle – he had a walkthrough of a Ty The Tasmanian Tiger level that just blew everyone else away. He’d thought about it, and made a level up. He couldn’t program, or really do art, but he did a simple little walkthrough video, and explained his thought processes. That was amazing. It gave him such competitive advantage.

One of the big things we look for when we’re interviewing people is their portfolio. Whether it be as an artist showing your work, or a programmer and having a playable game; that just puts you so far ahead of other people when you’re applying for a job. And even a designer, if you have a little walkthrough video. One of the guys we hired at Krome for Ty the Tasmanian Tiger 2 – Rob Davis, a graduate, who’s now working at Microsoft Games Studios in Seattle – he had a walkthrough of a Ty The Tasmanian Tiger level that just blew everyone else away. He’d thought about it, and made a level up. He couldn’t program, or really do art, but he did a simple little walkthrough video, and explained his thought processes. That was amazing. It gave him such competitive advantage.

Icons: Robert Forster

Icons: Robert Forster

I think it really depends on what you want to do. You get out of it what you need to. For certain jobs, it’s still quite necessary. I didn’t go the standard MBA route, but I did get a ton out of my experience, with two key points:

I think it really depends on what you want to do. You get out of it what you need to. For certain jobs, it’s still quite necessary. I didn’t go the standard MBA route, but I did get a ton out of my experience, with two key points: On copyright-related issues,

On copyright-related issues,  I think there are two key issues:

I think there are two key issues:

It just so happens that Jess is Digital Strategy Director at a mysterious Sydney advertising agency. She won’t say which, and she also won’t let me publish her surname. Or at leaIt’s not because she’s scared or nothin’, but on the internets, Jess is best known as the curator of a rather excellent blog called

It just so happens that Jess is Digital Strategy Director at a mysterious Sydney advertising agency. She won’t say which, and she also won’t let me publish her surname. Or at leaIt’s not because she’s scared or nothin’, but on the internets, Jess is best known as the curator of a rather excellent blog called

The career path to Digital Strategy Director was not an obvious one. I was a journalist, then moved to Melbourne and could not immediately get a journalism job so I got a job doing the overseas publicity for Neighbours [pictured right *snigger*]. I only got the job because at the interview I told the producer, “You know it’s not too late to make Izzie’s baby Jack’s,” or something. Since I was spending my days trying to get freelance writing work I had had plenty of time to watch Neighbours fortunately.

The career path to Digital Strategy Director was not an obvious one. I was a journalist, then moved to Melbourne and could not immediately get a journalism job so I got a job doing the overseas publicity for Neighbours [pictured right *snigger*]. I only got the job because at the interview I told the producer, “You know it’s not too late to make Izzie’s baby Jack’s,” or something. Since I was spending my days trying to get freelance writing work I had had plenty of time to watch Neighbours fortunately.

Tait Ischia

Tait Ischia