The Weekend Australian Magazine story: ‘Lockstep With Lockie: Santiago Velasquez and his guide dog’, November 2017

A feature story for The Weekend Australian Magazine, published in the November 25-26 issue. Excerpt below.

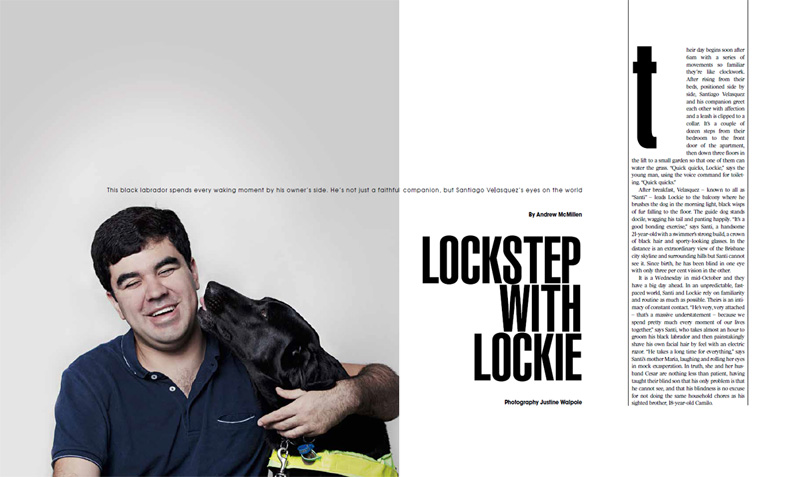

This black labrador spends every waking moment by his owner’s side. He’s not just a faithful companion, but Santiago Velasquez’s eyes on the world.

Their day begins soon after 6am with a series of movements so familiar they’re like clockwork. After rising from their beds, positioned side-by-side, Santiago Velasquez and his companion greet each other with affection and a leash is clipped to a collar. It’s a couple of dozen steps from their bedroom to the front door of the apartment, then down three floors in the lift to a small garden so that one of them can water the grass. “Quick quicks, Lockie,” says the young man, using the voice command for toileting. “Quick quicks.”

After breakfast, Velasquez — known to all as “Santi” — leads Lockie to the balcony where he brushes the dog in the morning light, black wisps of fur falling to the floor. The guide dog stands docile, wagging his tail and panting happily. “It’s a good bonding exercise,” says Santi, a handsome 21-year-old with a swimmer’s strong build, a crown of black hair and sporty-looking glasses. In the distance is an extraordinary view of the Brisbane city skyline and surrounding hills but Santi cannot see it. Since birth, he has been blind in one eye with only three per cent vision in the other.

It is a Wednesday in mid-October and they have a big day ahead. In an unpredictable, fast-paced world, Santi and Lockie rely on familiarity and routine as much as possible. Theirs is an intimacy of constant contact. “He’s very, very attached — that’s a massive understatement — because we spend pretty much every moment of our lives together,” says Santi, who takes almost an hour to groom his black labrador and then painstakingly shave his own facial hair by feel with an electric razor. “He takes a long time for everything,” says Santi’s mother Maria, laughing and rolling her eyes in mock exasperation. In truth, she and her husband Cesar are nothing less than patient, having taught their blind son that his only problem is that he cannot see, and that his blindness is no excuse for not doing the same household chores as his sighted brother, 18-year-old Camilo.

Downstairs at 9am, Santi reattaches the leash and repeats his voice command, while Lockie walks in circles and sniffs the lawn. “Quick quicks, buddy,” he says, and he means it: they have a bus to catch. Santi slips a fluorescent yellow harness over the dog’s head. With this action, Lockie has been trained to recognise that he is now in work mode, and his focus narrows to the singular task of guiding Santi from home to university — and, much later, back again. The dog is now six years old but has been in training since he was a puppy to fulfil this role. Santi never knew him as a puppy: Lockie was three when they first met on a rainy day at the Guide Dogs Queensland head office. Since January 9, 2015 — a date seared into Santi’s memory — they have scarcely spent an hour apart.

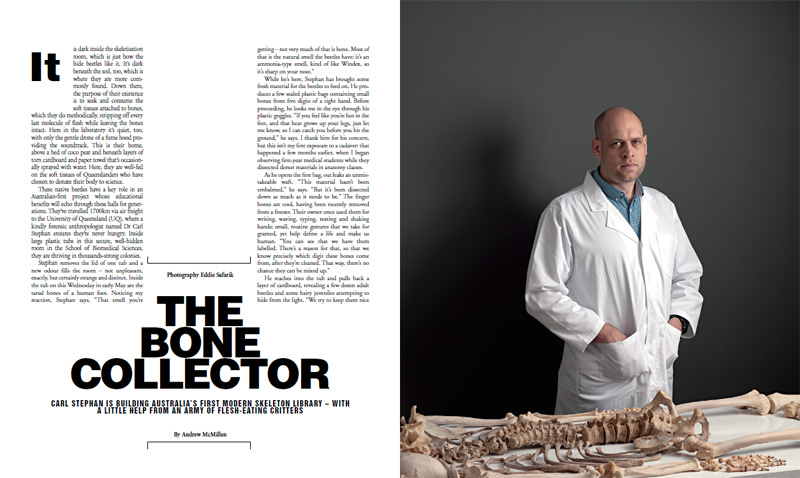

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: Justine Walpole.