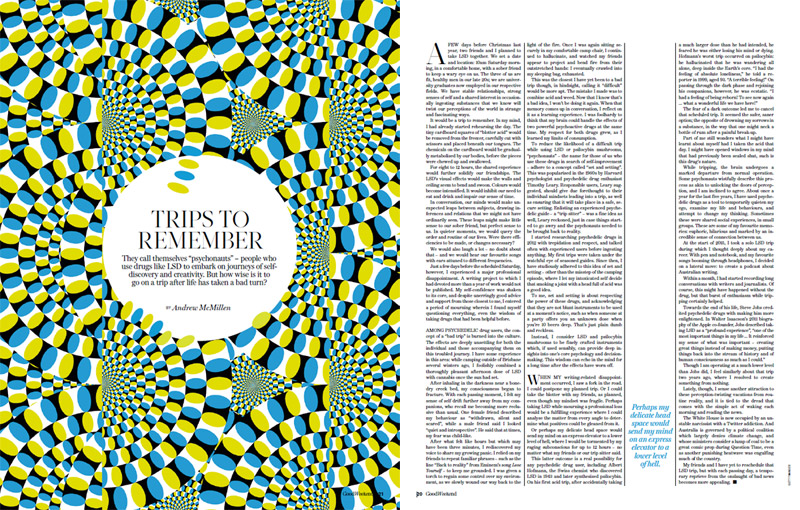

Good Weekend story: ‘Risky Business: How a bad LSD trip taught one Sydney teenager to think twice about experimenting with drugs’, September 2017

A feature story for Good Weekend, published in the September 30 issue. Excerpt below.

How a bad LSD trip taught one Sydney teenager to think twice about experimenting with drugs

Tom* closes his eyes, settles back on his bed, breathes in the aromatherapy oil he’s burning and listens to psychedelic trance while waiting for the onset of the trip from the LSD he’s just swallowed. It’s 8pm on a Friday night this year, he’s home alone in the sanctuary of his bedroom and he tells himself that this is his reward for finishing his exams (except for business studies, which he doesn’t care about). Within moments, the 17-year-old’s heart rate goes up, butterflies flutter in his stomach and waves of colour dance across his field of vision, regardless of whether he closes or opens his eyes. This is the fifth time he’s taken the hallucinogen, the first four with no unpleasant side effects, so he’s trying a double dose to see whether the sensations become more intense.

Tom takes precautions: he uses a drug-testing kit he bought from a “hippie store” near his house to make sure the drug is LSD rather than a more risky synthetic alternative. He cuts a tiny sliver from one of the tabs and drops it into a glass tube containing a small amount of liquid. He watches as the sample reacts to the chemicals, turning dark purple, indicating its purity. Satisfied, Tom eats four tiny pieces of LSD-soaked blotting paper known as “tabs”.

The trip starts well, reaching an idyllic plateau, but the come-up keeps climbing – and with it, his anxiety. He doesn’t hear his dad Karl* unexpectedly arrive home and climb the stairs. Sitting at his desk, Tom is so shocked when his dad opens his bedroom door that he can barely speak and doesn’t make eye contact. So odd is his behaviour that his father imagines he’s walked in on his son masturbating. Embarrassed, he bids his son good night – he’s off to meet Tom’s mum Jasmine* at a fund-raising dinner across town – and closes the door.

Tom is alone again, and the drug’s effects continue to intensify. Trying to counteract the restlessness he’s feeling, he walks onto the second-floor balcony off his bedroom and paces up and down. By now losing his sense of reality, Tom tries talking to himself in a bid to sort out the strange thoughts invading his mind. “Who’s doing this to you?” he asks, raising his voice. “Who’s doing this?”

Neighbours hear this bizarre phrase ringing out from the balcony. At first, they don’t associate the deep voice with Tom: it sounds almost Satanic. In the darkness, they can faintly see a figure pacing back and forth. They call out, asking if he’s all right. Well-known as an early morning runner, and well-liked as a trusted babysitter to several families in this quiet, affluent neighbourhood in Sydney’s north where he’s spent most of his life, Tom is clearly not himself. The family cats are howling, too, apparently as disturbed by his behaviour as the onlookers.

From the balcony, Tom scampers up onto the tiled roof, but loses his footing. A round, wooden table in the front yard breaks his fall not far from the edge of the swimming pool. The force of his weight smashes the furniture to pieces but he miraculously avoids serious injury. A concerned neighbour rings 000. Tom may be bleeding, but he’s still got the speed of a cross-country athlete and seemingly superhuman strength, despite his reed-thin frame. He rushes back inside his house, tracking blood through different rooms, before smashing a back fence then running onto the street again, tearing off his clothes.

What happens over the next hour or so – Tom breaking a window of a neighbour’s house, neighbours chasing him, making him even more paranoid and fearful – is a blur. He winds up several streets from home, lying naked in the middle of the road, surrounded by people looking down at him, including two female police officers and paramedics. It takes a few of them to handcuff him.

Hovering not far away is a television news crew, which has received a tip-off about the disturbance. Tom is at risk of having the worst moment of his life spread over the news, but the police are able to keep the media at bay because he’s a minor. All the while, Tom continues to ramble incoherently: “The universe is against us! The universe is against us!”

At the fund-raising dinner which his parents are attending, Karl is perplexed when his phone begins to vibrate during a speech. Jasmine also grabs her phone, which is lighting up with messages from five different neighbours asking her to call them immediately. The couple hurriedly excuse themselves before Jasmine calls a trusted friend. “Tom’s all right,” she’s told. “But you need to go straight to the hospital.” On arrival around midnight, they’re greeted by a sight that haunts all parents: their teenage son unconscious in a hospital bed, covered in dried blood, with plastic tubes snaking out of his mouth and nose.

To read the full story, visit Good Weekend. Above illustration credit: Clemens Habicht.