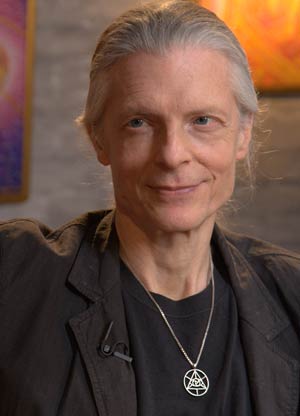

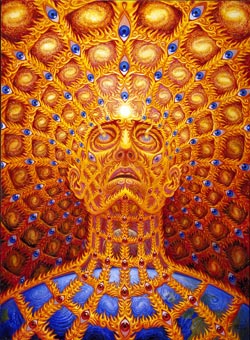

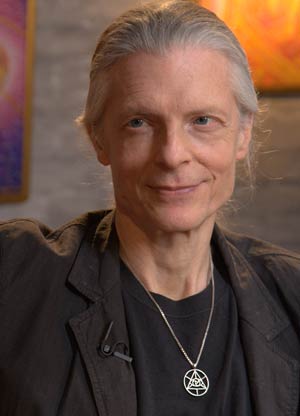

In early January 2011, I was scheduled to interview the American visionary artist Alex Grey [pictured right] for The Australian ahead of his first Australian art tour. The problem was that at the time, my home city of Brisbane was in the midst of some of its worst-ever flooding.

In early January 2011, I was scheduled to interview the American visionary artist Alex Grey [pictured right] for The Australian ahead of his first Australian art tour. The problem was that at the time, my home city of Brisbane was in the midst of some of its worst-ever flooding.

Due to a sketchy internet connection, I didn’t want to risk the possibility of a Skype video call dropping out mid-interview, so I sent through some questions for Alex and his wife Allyson to answer via email. Their answers formed the basis of my 800 word story for The Australian, which you can read here.

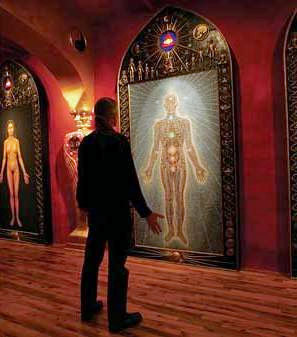

Our full email interview is below; Alex’s answers are included verbatim, without editing. Examples of Alex’s striking art are embedded throughout this interview.

++

Andrew: Many readers of The Australian would be unfamiliar with your work. How would you describe your painting styles to those who haven’t seen it before?

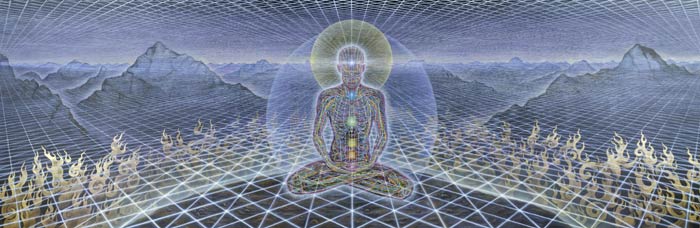

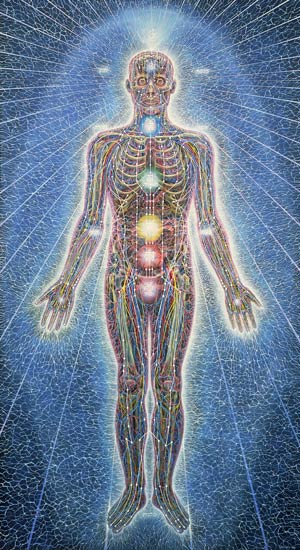

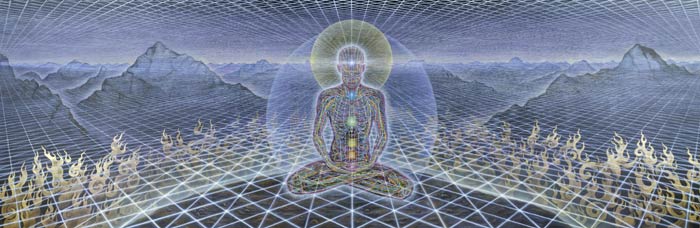

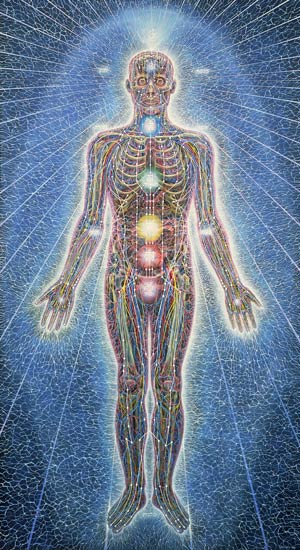

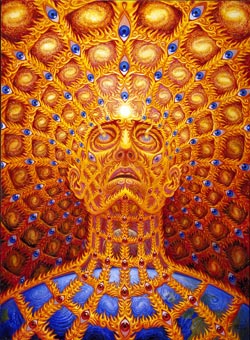

Alex: My best known works are paintings that “X-ray” multi-dimensional reality, interweaving biological anatomy with psychic/spiritual energies in visual meditations on the nature of life and consciousness.

Is there an intellectual rationale behind your work? Has this changed much over the years?

My work has been called visionary because I’m a painter inspired by glimpses into the subtle visionary realm, which is the source of all sacred art. There is more of a spiritual motivation to the work. The philosophical framework from which one could view the artwork is an integral and consciousness evolutionary perspective. This is a crucial time for humanity when all the world religions are becoming familiar with each other. Art can play a special role in bridging these traditions, thereby helping to make peace in a volatile climate. A planetary civilization is dawning. We need fresh iconography that points to a sustainable relationship of humanity, the web of life and harmony amongst nations.

What do you aim to communicate in your art?

Life is multi-dimensional and all beings and things are interconnected. The cosmos is a continuum in which every creature plays an important part. Our bodies are marvelous gifts of biological evolution that we have the good fortune to experience in our brief life span. Life is a miracle. Love is the highest principle and experience and is the way of all religious teachings.

I’m interested in each of your painting methods. What materials do you use? After visualising a piece, where do you start, in terms of the actual painting? Do you prefer to spend long periods of time painting, or is it split up into many shorter sessions?

We both paint with acrylic but prefers oils. We paint on linen and on wood panels. In Alex’s art, everything starts with a vision that results in a drawing and a redrawing over and over again until it is refined enough to transfer the image to canvas or wood. We both love painting for long periods. Sometimes when we have painted together for as long as 20 hours straight.

We are also founders of a church on 40 acres of land with over a dozen employees and many volunteers. We have many responsibilities that fill our days. This is not a distraction from the artwork. This is a realization of the “great work” which is to build a temple of art that we call the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors.

Do you listen to music while you work?

Almost always. Sometimes we listen to wisdom teachings on audio.

Which artists do you listen to?

Bach, Beethoven, Shubert, Shpongle, Ott, Fats Waller, Led Zepplin, Tool, loads of trance music, Toires, Heyoka, Crystal Method, Animal Collective, Bob Dylan, Canned Heat, Joe Satriani, John Fruscianti, Moby, Peter Gabriel, The Beastie Boys, Clash, Stones, The Beatles. George Harrison and Sting are mystics. Recently, at Daniel Pinchbeck’s documentary film premiere of 2012, Sting came up and hugged Alex. We were starstruck.

Our daughter Zena queues us into a lot of new music.

Your larger pieces are often reduced in size to appear in various media – books, calendars, postcards, and on the web. Do you find this dismaying at all? Is anything lost in the art, when it’s reduced from the original size?

Your larger pieces are often reduced in size to appear in various media – books, calendars, postcards, and on the web. Do you find this dismaying at all? Is anything lost in the art, when it’s reduced from the original size?

It’s a representation of the work for the purpose of reaching a wider audience. Reproductions are not just smaller, they are NOT the original. To the see the original is a more direct hit. There is still power in a reproduced image, though. It’s just through a glass darkly. An artwork has power when it is iconically viable from the size of a postage stamp to the size of a billboard.

We produce or license images and sell them to benefit the building of a sacred temple.

Many people – myself included – first found your work through Tool album covers. I believe your work has been used by some other musical acts, too. Was there any hesitation in being involved with these projects?

Or am I just THAT sort of Rock Whore? Am I just a trollup in a beret? Just kidding.

No. People had told me that I would love TooI. I was having an exhibition in Santa Monica when Adam Jones became interested in my work. This motivated me to listen to their music. I was kind of a late comer. Allyson and I were immediately bowled over. We’re huge fans and look forward to seeing them on our last night in Australia.

I’ve met Adam Yauch of The Beastie Boys. We are both rather avid scholars of Tibetan Buddhism and we hung out once at a Dalai Lama event. That was so cool.

We love the guys in S.C.I. and are particularly friendly with Michael Kang who we often see at festivals like Burning Man. What fine musicians they all are. It’s an honor to know such artists.

My work appeared on the last Nirvana album cover, In Utero. I heard that Kurt Cobain liked my work but I never met him or went to a Nirvana concert.

Are there any Tool collaboration projects forthcoming?

No. There is nothing planned at this time.

I believe you both teach (or taught – past tense?) Visionary Art at The Open Centre. What are some of the values that you try to instill in the students who take your courses?

We have taught visionary art at many centers all over the world. We recently taught a workshop in Moscow with a Russian translator and then in Mexico City with a Spanish translator. We look forward to teaching a three-day Visionary Art workshop in Byron Bay, January 25-27 [2011].

At CoSM, the art and spirit educational nexus is called MAGI — Mystic Artists Guild International. We teach art as a spiritual path. We just had a workshop before the Full Moon ceremony called, “Visioning Your Highest Intention.” The purpose of MAGI is to form a higher social organism of inspired minds capable of building sacred space together. Sacred space has always been created by the intertwined wills of people dedicated to a divine purpose. Creating and sharing sacred art can be a form of worship and service, introducing a transformed world view to community and activating cultural renewal. The MAGI bear gifts of beauty for the newly born vision of planetary civilization and universal spirituality. Mystic artists are called to an authentic and disciplined manifestation of their visions.

I’ve read in High Times that you work in your loft, where you prefer to have your family and library nearby. How do you deal with distractions while working? Do you have an ‘artist at work’ sign posted somewhere?

I’ve read in High Times that you work in your loft, where you prefer to have your family and library nearby. How do you deal with distractions while working? Do you have an ‘artist at work’ sign posted somewhere?

Allyson and I have worked within eye shot of each other for thirty-six years. We are each others best friend and most honest critic and advisor. I like to work near all my source material of imagery and philosophy.

Zena grew up here. When Zena came, Allyson and I had already been together for thirteen years and had already developed our rhythm as artists. Zena has been the greatest gift of our lives.

What is a distraction? The path to building a temple is a big project. The project IS our art so we are always making our art.

We are trusted filters for each other. We always have the others best interests at heart.

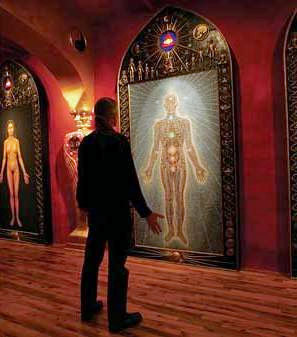

Arguably your most famous works, The Sacred Mirrors, took a decade to complete. What do you recall from that time? Did you realize that you were creating works that would come to define you as an artist?

Painting the Sacred Mirrors felt life defining. Allyson inspired and later named the Sacred Mirrors series. The idea would never otherwise have been realized. At that time, they were the most affirmative statement I could make as an artists to connect the human and the divine, a dissection of the self through the layers of body and soul. The paintings pointed in the direction of a new kind of figuration for me, something I call, “Transfiguration,” the physical body in relationship to transcendental light. The work has a universally sacred aspiration.

The other beautiful thing that the Sacred Mirrors memorialize is one of our most profound psychedelic experiences. The Universal Mind Lattice visually recounts a meltdown of the physical body into the white light torroidal fountain and drain of energy. What really completely reformatted our psychic hard drive was that Allyson and I did drawings of the same place. We both saw our infinite interconnectedness with the great web of all existence, a love energy flowing through all beings and things.

What is your proudest artistic achievement?

What is your proudest artistic achievement?

Yet to come.

I was reading an article about the New Year’s Eve just passed, and the scope of the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors [CoSM] in Wappinger. It seems like a massive undertaking, yet having not visited, it’s hard to picture. Could you help me out by describing the space?

The mission is formidable and ultimately doable. Collectors have actually donated works back to CoSM to be part of this great project. Many artists resonate with the practice of art as their spiritual life.

CoSM lives on 40 wooded acres in the Hudson Valley of New York, 65 miles north of New York City, walking distance from a railroad station running from Manhattan’s Grand Central Station. CoSM has six buildings and a barn and one by one we are make them beautiful and enjoyable as we design and prepare to build the sacred temple. A small staff lives on the property and many volunteers come to joyfully serve the project. We started holding Full Moon ceremonies in our home in Brooklyn in 2003, had a spiritual creative art center in Manhattan for five years, and now an artists refuge.

What does the Chapel mean to each of you?

The Chapel of Sacred Mirrors is yourself, the temple of your body and the temple of your spirituality. Art is a fusion of those elements. God/love is what brings them together. Love is the secret name of God. When you surrender to love you see through God’s eye. That is what you see when you are staring at a Sacred Mirror.

Building a Chapel is the work of a community. If we all get along we can make something beautiful together. If we do not get along, our progress is impaired in making something beautiful and of having a sustainable relationship with the planet.

Unless I’m mistaken, you seem to both now thrive on the notion of patronage – you’re financially supported by your fans and followers, who pay you to express yourselves through art. Was this always the goal?

Unless I’m mistaken, you seem to both now thrive on the notion of patronage – you’re financially supported by your fans and followers, who pay you to express yourselves through art. Was this always the goal?

We travel because we are invited. To make art and have others love it and want to see it is a terrific honor. Every creative person yearns to live by their creativity. Our art is our ministry. We decide what art we are making and we make it to serve the greater good. Many creative people are considering the ethical energy that they are putting into their manifestations. A moral element deepens the narrative.

Do you remember if there was a particular moment when you realized you were a self-sufficient artist, who no longer had to take on projects for commercial clients?

I live and work to serve others.

At 17 I painted Fun Houses. At 19 I painted billboards. At 21 I worked in the Anatomy department at Harvard Medical School, preparing exhibits on the history of medicine and disease and preparing cadavers for dissection by medical students. At 26 I was a medical illustrator and for ten years I taught anatomy to art students at New York University (NYU). Chapel of Sacred Mirrors became a non-profit organization in 1996 and at age 45 I stopped doing medical or other types of illustration work. Since then, I paint, sculpt, study, teach, lecture, write, work everyday as a co-founder and director of CoSM, now a church.

What would retirement look like for you two? It seems hard to imagine you giving up your public roles as CoSM owners and operators. Finally, what would you each like to be remembered for?

For as long as we are breathing we will be working on this project. Why retire from a life you love? We’ve been given a project to dedicate our lives to. What a gift! It will involve many visionaries who are our friends. Everyone is welcome.

We’d like to be remembered for a universal spiritual message that reunifies the sacred visionary imagination with the art of our time.

Of course, we’d like to be represented by the completed and sustainable building of the Chapel of Sacred Mirrors.

++

To learn more about Alex Grey, visit his website.

Elsewhere: my story for The Australian about Alex Grey’s first Australian art tour, published in January 2011.

In early January 2011, I was scheduled to interview the American visionary artist

In early January 2011, I was scheduled to interview the American visionary artist

Your larger pieces are often reduced in size to appear in various media – books, calendars, postcards, and on the web. Do you find this dismaying at all? Is anything lost in the art, when it’s reduced from the original size?

Your larger pieces are often reduced in size to appear in various media – books, calendars, postcards, and on the web. Do you find this dismaying at all? Is anything lost in the art, when it’s reduced from the original size?

What is your proudest artistic achievement?

What is your proudest artistic achievement? Unless I’m mistaken, you seem to both now thrive on the notion of patronage – you’re financially supported by your fans and followers, who pay you to express yourselves through art. Was this always the goal?

Unless I’m mistaken, you seem to both now thrive on the notion of patronage – you’re financially supported by your fans and followers, who pay you to express yourselves through art. Was this always the goal? Benjamin Law’s book deals with his wonderfully dysfunctional family

Benjamin Law’s book deals with his wonderfully dysfunctional family