Guardian Australia story: ‘”His Death Still Hurts”: Pfizer anti-smoking drug Champix ruled to have contributed to suicide’, September 2017

A feature story for Guardian Australia. Excerpt below.

‘His Death Still Hurts’: the Pfizer anti-smoking drug ruled to have contributed to suicide

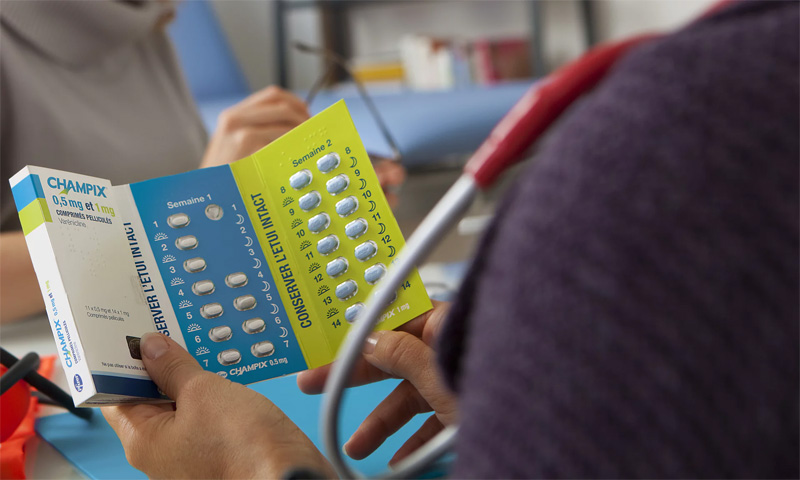

An Australian coroner says Champix had a role in Timothy John’s death, which occurred after only eight days on the drug

When the retired Queensland schoolteacher Phoebe Morwood-Oldham started an online petition following her son’s suicide in April 2013, she could not have known that her insistence on asking hard questions of one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies would lead to an Australian-first finding by a state coroner.

On Thursday in Brisbane magistrates court, coroner John Hutton found that a commonly prescribed drug named Champix – manufactured by Pfizer and sold internationally under the name Chantix – contributed to the death of a 22-year-old Brisbane man, Timothy John, who died by suicide soon after he began taking a medication that he had hoped would cut his smoking habit from eight cigarettes a day down to zero.

For Morwood-Oldham, the finding was a satisfying outcome for a lengthy process that began with a Change.org petition that she started four years ago, which asked for on-the-box warning labels on Champix packaging. It has been signed by 49,000 people. “His death still hurts so deep,” she wrote at the top of the petition. “After taking the anti-smoking drug marketed as ‘Champix’ for just 8 days, my beautiful boy hung himself. But despite reports of 25 suicides linked to Champix in seven years – there still aren’t proper side-effect warnings.”

Every Sunday for four years Morwood-Oldham and her older son, Peter, have visited Timothy’s grave at Cleveland cemetery. The weekly routine involves the laying of lillies and turning their minds toward a young man who was, as his headstone says, “much wanted and loved”. Morwood-Oldham tells Guardian Australia that Timothy’s death “was so sudden” and it affected her deeply.

“I lost the person I love the most in the world, in eight days. I never expected it.”

Talking about Timothy, Morwood-Oldham warns that her emotions are “all over the place”. He is never far from his mother’s mind, nor her gaze: when she opens her laptop to share some photographs, there he is, her screensaver. A cute, blond boy aged six, aiming a cheeky smile at the lens.

Timothy had suffered mental health issues, something his mother speaks of in terms of grades out of 10. He had for a time been a 4/10, then, after cognitive behaviour therapy, he was back to 9/10.

“How did he go from a 9/10 to a 1/10 in eight days on Champix?” she said. “The autopsy showed there were no alcohol or drugs in his system other than Champix and Ibuprofen.”

The inquest heard that, on a drive back from the Gold Coast just hours before his death, Timothy asked, “Mum, do you think I should give up the Champix? It’s making me feel strange.” Morwood-Oldham told the original two-day inquest in November last year: “I said to him, ‘Timothy, if it’s helping you to give up smoking maybe you keep it up’.” She had not been part of the consultations with her son’s GP when he was prescribed the drug and the Champix packaging did not contain warnings for any potential adverse effects.

To read the full story, visit Guardian Australia.

For help if you are in Australia: Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Lifeline 13 11 14, Survivors of Suicide Bereavement Support 1300 767 022. For help if you are outside of Australia, visit suicide.org’s list of international hotlines.

Icons: Robert Forster

Icons: Robert Forster Here’s my first story for

Here’s my first story for