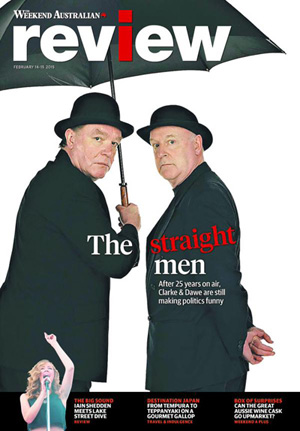

The Weekend Australian Review story: ‘Sight Unseen: Audio description for blind theatregoers’, September 2017

A feature story for The Weekend Australian Review. Excerpt below.

For theatregoers with impaired vision, audio description services help to make sense of what’s happening on stage.

You are sitting in the front row of a theatre when a calm, male voice begins to speak into your ear, welcoming you and setting out key details about the play you are here to see. “The Merlyn theatre is a flexible, black-box theatre space,” says the voice. “For Elephant Man, the audience sits in a rectangular seating bank opposite to the stage. The stage is raised about 40cm off the ground, and takes up the full width of the Merlyn, about 10m wide.”

You are listening intently to the voice because you cannot see what it is describing. You are blind, but you love going to the theatre, and you want to better understand the performance beyond the dialogue that all attendees can hear from the stage. This is why you are at the Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne’s inner city on a rainy Friday night, listening as the shape and layout of the stage begins to take shape in your mind’s eye.

“A black proscenium arch frames the playing area, about 5m tall, creating a wide rectangular space,” continues the voice. “A curtain of black gauze covers the entire width of the stage at its front edge, separating us from the playing area. We can see through the sheer material, but it softens the edges of everything behind it.”

You are hearing the voice because your earphones are connected to a wireless radio receiver that sits inside the palm of your hand. Later, this wonderful technology will allow you to follow the action you can’t follow with your eyes.

While the boisterous audience take their seats behind you in the minutes before a performance of The Real and Imagined History of the Elephant Man begins, you are listening to pre-show notes that are being broadcast into your ears from the green room on the building’s third floor. There, a bespectacled 26-year-old named Will McRostie sits before a computer, a live video feed of the stage, and some audio equipment that allows him to speak into the ears of theatregoers who have registered for audio description services this evening.

“The play makes extensive use of smoke and haze effects,” says McRostie’s voice. “Nozzles emitting smoke are hidden in the walls of the set, sometimes leaking heavy mist that tracks along the ground, and sometimes blasting plumes of light smoke that billows to fill the space. Two powerful fans set into the floor of the space are sometimes activated to catch this smoke and propel it toward the ceiling. On occasion, the smoke is so heavy it becomes difficult to see the performers.”

Difficulty in seeing the performers is the entire purpose of audio description, a niche and little-known service that is sometimes — but not often — available for people with low vision who attend theatres and cinemas. Because of its exclusivity and the resources required to produce the service, it is usually available only in Australia’s capital cities, and only for the biggest productions on the annual theatre and cinema calendars.

To date, audio description has largely been provided in an ad hoc manner by volunteers and, as a result, the quality of the service experienced by blind patrons can vary wildly. McRostie is at the forefront of a movement to professionalise it, however, which is why he founded an arts start-up named Description Victoria in March this year.

To read the full story, visit The Australian. Above photo credit: David Geraghty.