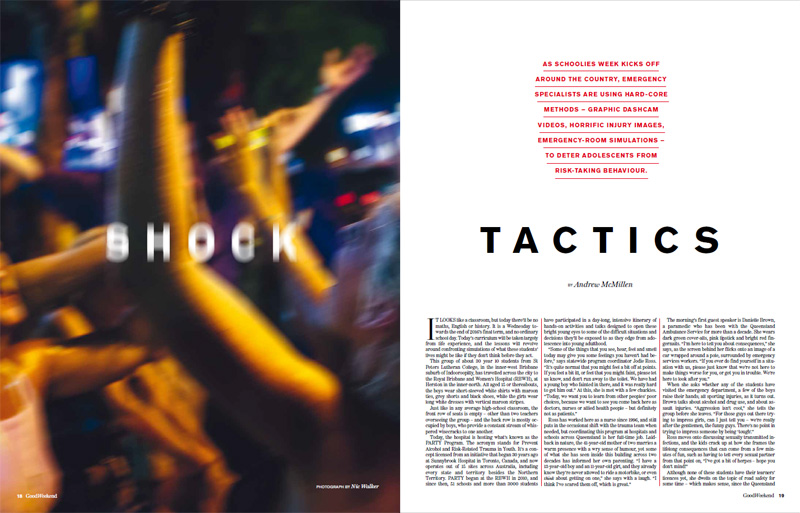

Shock Tactics

As Schoolies Week kicks off around the country, emergency specialists are using hard-core methods – graphic dashcam videos, horrific injury images, emergency-room simulations – to deter adolescents from risk-taking behaviour.

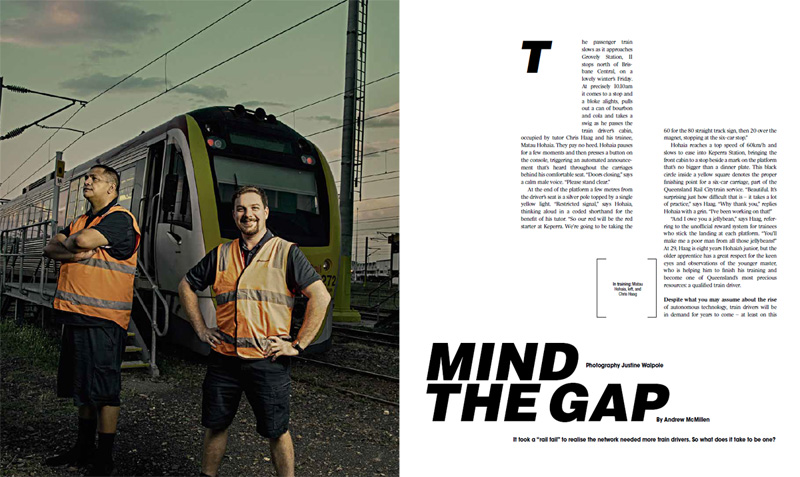

It looks like a classroom, but today there’ll be no maths, English or history. It is a Wednesday towards the end of 2016’s final term, and no ordinary school day. Today’s curriculum will be taken largely from life experience, and the lessons will revolve around confronting simulations of what these students’ lives might be like if they don’t think before they act.

This group of about 30 year 10 students from St Peters Lutheran College, in the inner-west Brisbane suburb of Indooroopilly, has travelled across the city to the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital (RBWH), at Herston in the inner-north. All aged 15 or thereabouts, the boys wear short-sleeved white shirts with maroon ties, grey shorts and black shoes, while the girls wear long white dresses with vertical maroon stripes. Just like in any average high-school classroom, the front row of seats is empty – other than two teachers overseeing the group – and the back row is mostly occupied by boys, who provide a constant stream of whispered wisecracks to one another.

Today, the hospital is hosting what’s known as the PARTY Program. The acronym stands for Prevent Alcohol and Risk-Related Trauma in Youth. It’s a concept licensed from an initiative that began 30 years ago at Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto, Canada, and now operates out of 15 sites across Australia, including every state and territory besides the Northern Territory. PARTY began at the RBWH in 2010, and since then, 51 schools and more than 3000 students have participated in a day-long, intensive itinerary of hands-on activities and talks designed to open these bright young eyes to some of the difficult situations and decisions they’ll be exposed to as they edge from adolescence into young adulthood.

“Some of the things that you see, hear, feel and smell today may give you some feelings you haven’t had before,” says statewide program coordinator Jodie Ross. “It’s quite normal that you might feel a bit off at points. If you feel a bit ill, or feel that you might faint, please let us know, and don’t run away to the toilet. We have had a young boy who fainted in there, and it was really hard to get him out.” At this, she is met with a few chuckles. “Today, we want you to learn from other peoples’ poor choices, because we want to see you come back here as doctors, nurses or allied health people – but definitely not as patients.”‘

Ross has worked here as a nurse since 1996, and still puts in the occasional shift with the trauma team when needed, but coordinating this program at hospitals and schools across Queensland is her full-time job. Laidback in nature, the 41-year-old mother of two marries a warm presence with a wry sense of humour, yet some of what she has seen inside this building across two decades has informed her own parenting. “I have a 13-year-old boy and an 11-year-old girl, and they already know they’re never allowed to ride a motorbike, or even think about getting on one,” she says with a laugh. “I think I’ve scared them off, which is great.”

The morning’s first guest speaker is Danielle Brown, a paramedic who has been with the Queensland Ambulance Service for more than a decade. She wears dark green cover-alls, pink lipstick and bright red fingernails. “I’m here to tell you about consequences,” she says, as the screen behind her flicks onto an image of a car wrapped around a pole, surrounded by emergency services workers. “If you ever do find yourself in a situation with us, please just know that we’re not here to make things worse for you, or get you in trouble. We’re here to look after you.”

When she asks whether any of the students have visited the emergency department, a few of the boys raise their hands; all sporting injuries, as it turns out. Brown talks about alcohol and drug use, and about assault injuries. “Aggression isn’t cool,” she tells the group before she leaves. “For those guys out there trying to impress girls, can I just tell you – we’re really after the gentlemen, the funny guys. There’s no point in trying to impress someone by being ‘tough’.”

Ross moves onto discussing sexually transmitted infections, and the kids crack up at how she frames the lifelong consequences that can come from a few minutes of fun, such as having to tell every sexual partner from that point on, “I’ve got a bit of herpes – hope you don’t mind!”

Although none of these students have their learners’ licences yet, she dwells on the topic of road safety for some time – which makes sense, since the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads is the program’s primary funding source: in August, it provided an additional $1.54 million to keep the statewide initiative topped up for another three years. During this part of the presentation, the screen shows dashcam footage from cars where teenage drivers were distracted by their phones. These videos are horrifying to watch: the drivers’ eyes remain in their laps, even as the car veers outside the painted lines and towards needless trauma.