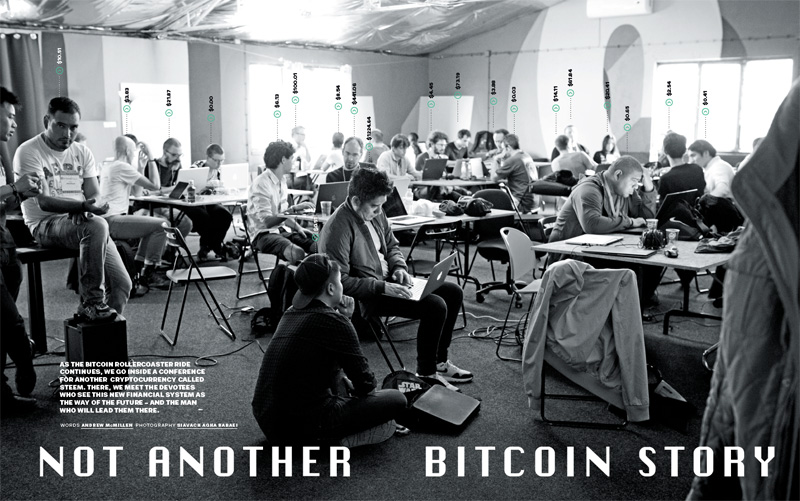

GQ Australia story: ‘Not Another Bitcoin Story: Steemit and Steemfest’, March 2018

A feature story for GQ Australia, published in the March/April 2018 issue. Excerpt below.

As the Bitcoin rollercoaster ride continues, we go inside a conference for another cryptocurrency called Steem. There, we meet the devotees who see this new financial system as the way of the future – and the man who will lead them there.

On the stage in front of us stands a clean-shaven young man, his short brown hair slicked back at the fringe. Dressed in a plain black T-shirt and dark jeans rolled up to reveal heavy brown boots, his name is Ned Scott, a 27-year-old former-financial-analyst-turned-tech-entrepreneur who looks remarkably, well, normal. The kind of guy who could easily slot into your social sport team, then buy you a beer after the game. But he also happens to be a millionaire many times over.

Before him sits an audience of 300 men and women who are each hoping to become as rich as Scott, simply by posting on a website named Steemit. Co-founded by Scott, the site officially went live in July 2016 and has since paid out more than $25m in digital currency to its users. These devotees have travelled from more than 35 countries around the world – each paying as much as AUD$1500 – for the privilege of attending this, the second annual Steemfest conference in Lisbon, Portugal.

Sporting the kind of wireless headset you might catch Madonna wearing on stage, Scott projects easy confidence as he gives a presentation to open the first day of Steemfest. Hundreds of people have gathered to pray at the altar of this new technology, which might change the shape of the world’s entrenched financial systems. For about 15 minutes, Scott addresses the crowd, who are mostly listening in respectful silence but occasionally erupt into cheers and applause.

“The thing that’s probably more important than anything else,” Scott tells the crowd, as his talk draws to a close, “is actually something I can describe in one word.” He clicks the device in his hand to reveal the final slide of his presentation, which features just three large letters.

“You,” he announces, gazing at the neat rows of occupied seats. “You go out there, and you’re bringing the passion, interest and value to the project. Everything that you guys do is what matters. The technology is just a vehicle for you; for us. And I’m looking forward so much to what you’re going to do over the next several years, as we grow, and go to the moon.”

The crowd erupts in whoops and cheers, raising their phones to snap photos of Steemit’s leader, who looks down fondly on his flock.

It’s all very energetic. And it’s hard to avoid the feeling there is something of an air of cult-like fervour in the room. In fact, it’s a sensation that permeates the entire conference. From the jubilant reception for Scott’s keynote speech, to the closing dinner a few nights later, when the charming Dutch MC leads the crowd in a chant of “Steem! Steem! Steem!”

These people are the true believers; invested, in every sense, in a digital currency that they cannot see or touch. Which brings us to an obvious question: what exactly is Steemit?

While you’re sharing memes and holiday snaps on Facebook, these 300 devotees – and their global community of more than 400,000 Steemit users – are earning digital dollars for posting on the site.

Its point of difference from other social networks is that the entire website is powered by a cryptocurrency called Steem and each post, comment and like earns its users tiny fractions of the currency. Over time, at least in theory, it is possible to accumulate a substantial amount of Steems that users could eventually cash in for cold, hard Aussie dollars.

Or maybe not. The site’s layout feels pretty clunky, especially for those accustomed to the smooth, easy-to-use platforms seen elsewhere on the web. Plus, we’ve been posting on Steemit for little more than a year and our estimated account value sits at around AUD$1900. Better than nothing, but it’s probably a little early to start picking out waterfront properties. Still, even if our contributions to Steemit eventually earn us just a single, shiny dollar, that’s a gold coin more than we ever earned posting memes on Facebook.

To read the full story, visit GQ Australia. Above photo credit: Siavach Agha Babaei.

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as

In Digital Vertigo [pictured right], Anglo-American entrepreneur Andrew Keen takes a critical stance against the technologists behind social networking tools such as Facebook and Twitter, for reasons exemplified in the book’s subtitle. Keen knows his topic from the inside: on the cover the title is presented as a Twitter hashtag and the author’s name as  Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

Conversely, British novelist Nick Harkaway tries his hand at long-form nonfiction for the first time in The Blind Giant [pictured right], and strikes on a narrative that immediately grips the reader. Using tight language and evocative descriptions, Harkaway’s introduction is a nightmare vision of a dystopian, tech-led society where “consciousness itself, abstracted thought and a sense of the individual as separate from the environment” are all withering away. A contrasting vision of a “happy valley” follows, and is just as realistic and compelling.

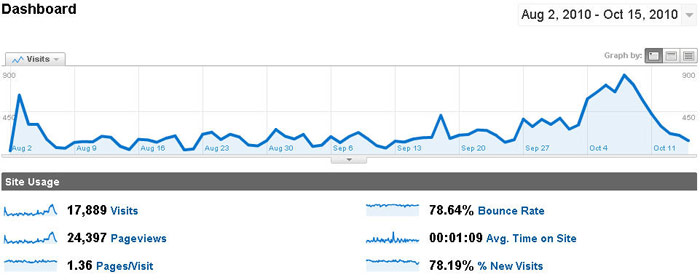

A couple of months ago I undertook a

A couple of months ago I undertook a

This year, One Movement Word’s blog content was split into the following categories – click for further info:

This year, One Movement Word’s blog content was split into the following categories – click for further info: and by far the best music industry panel I’ve witnessed. Which doesn’t sound that impressive, really, but trust me: Nick and his panelists touched on some brilliant, universally-understood topics, like pursuing your passion, the nature of independence, and being kind to others without expectation of repayment. I’ll say no more; you’ll have to read my

and by far the best music industry panel I’ve witnessed. Which doesn’t sound that impressive, really, but trust me: Nick and his panelists touched on some brilliant, universally-understood topics, like pursuing your passion, the nature of independence, and being kind to others without expectation of repayment. I’ll say no more; you’ll have to read my

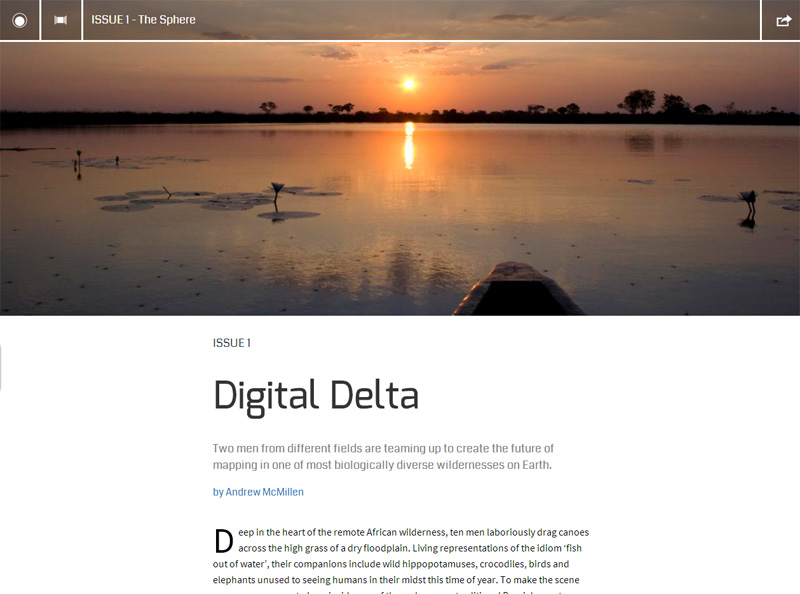

While still valuing conventional books, Reiter [pictured right] believes publishers need to embrace emerging digital technology. In his mind, the biggest problems facing Australian independent publishers are market access and international promotion. Yet, he argues, these concerns are largely side-stepped through digital media. “We’ve have been able to bypass some of the traditional channels – overseas agents, overseas distributors, selling rights to overseas publishers – by having a significant online presence.”

While still valuing conventional books, Reiter [pictured right] believes publishers need to embrace emerging digital technology. In his mind, the biggest problems facing Australian independent publishers are market access and international promotion. Yet, he argues, these concerns are largely side-stepped through digital media. “We’ve have been able to bypass some of the traditional channels – overseas agents, overseas distributors, selling rights to overseas publishers – by having a significant online presence.” Despite their significant investment in digital media, IP haven’t abandoned the traditional format. One of the publisher’s most recent print edition books is A Beginner’s Guide to Dying in India. Reiter discovered its author, Josh Donellan [pictured left], after the Brisbane local entered

Despite their significant investment in digital media, IP haven’t abandoned the traditional format. One of the publisher’s most recent print edition books is A Beginner’s Guide to Dying in India. Reiter discovered its author, Josh Donellan [pictured left], after the Brisbane local entered  That’s all well and good. But, as Donellan himself argues, in all this talk about print versus digital, the most fundamental element of book publishing seems to be missing. “I think there’s a danger that sometimes the focus on the packaging outweighs the matter itself,” says Donellan. “I think [digital publishing is] an important change, but it still really matters how good the material is.”

That’s all well and good. But, as Donellan himself argues, in all this talk about print versus digital, the most fundamental element of book publishing seems to be missing. “I think there’s a danger that sometimes the focus on the packaging outweighs the matter itself,” says Donellan. “I think [digital publishing is] an important change, but it still really matters how good the material is.”