In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks. All Tomorrow’s Parties was the main reason. It’s an independently-operated festival that celebrated its 10th anniversary with a weekend-long concert series held at Butlins holiday camp, in the town of Minehead near England’s west coast. We stayed on-site for 10 days all up – including the Nightmare Before Christmas weekend curated by My Bloody Valentine, the ‘in between days‘ series of weeknight shows, and the 10 Years Of ATP weekend – and saw a ridiculous amount of good music. Which was the intended outcome.

In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks. All Tomorrow’s Parties was the main reason. It’s an independently-operated festival that celebrated its 10th anniversary with a weekend-long concert series held at Butlins holiday camp, in the town of Minehead near England’s west coast. We stayed on-site for 10 days all up – including the Nightmare Before Christmas weekend curated by My Bloody Valentine, the ‘in between days‘ series of weeknight shows, and the 10 Years Of ATP weekend – and saw a ridiculous amount of good music. Which was the intended outcome.

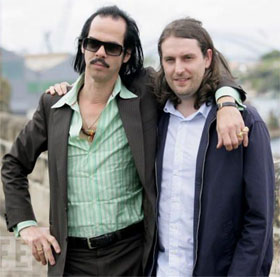

While on-site, I interviewed ATP founder Barry Hogan [pictured right] for a Rolling Stone story. [I also reviewed Dirty Three playing ‘Horse Stories’ to around 100 people, for Mess+Noise.] Late on the Sunday night of the 10 Years event – after sacrificing my barrier spot for The Mars Volta – we sat down in the production office to discuss the festival’s history and his motivations for creating what has become an internationally successful event.

Andrew: Barry, broadly speaking, what do you think has contributed to ATP’s success as a festival?

Barry: When ATP started 10 years ago, there weren’t any alternative festivals. It was only big corporate festivals and I think a lot of people who are into bands like Low, Will Oldham, and so on, the only place you could see them was at Reading Festival and that sort of thing, and they’d be kind of sandwiched in with piles of shit like Carter The Unstoppable Sex Machine and fuckin’ Chumbawumba. It just felt like you paid whatever it was at the time, £80-90 to go for the day, but you’d have to wait all day to see something [worthwhile].

I just thought, “Wouldn’t it be great if we could design something where you could have constant bands, all day long, you’re wanting to go and see things, like killing yourself that you’re missing something because something else is on that the same time,” and just do it in a more intimate environment. Glastonbury, for example, was one of the reasons why we wanted to hold it here in the [Butlins] holiday camp, because of the conditions there. I think the toilets in Guantanamo Bay are probably healthier than there. Glastonbury is an abomination. It’s like the way it’s designed is for too many people in too small a space, and I thought, “this isn’t fun”. But here, people have got their own apartments, their own space. Going back to your question; what’s contributed to it, is we’ve designed it so we want to treat people like we want to be treated, and we want people to be into really good music, have a good time, enjoy themselves, and feel like they got value for money.

I feel that because we’ve been true to the concept of keeping it sponsorship-free, and also keeping the idea of the curator and being sort of focused on that, I think that’s definitely one of the reasons why it’s remained as strong as it has over the years. We’ve just got a loyal fan base that continually comes back. It’s good.

Is it difficult to stay true to the concept, to keep focused?

It is if the curator doesn’t go mental with trying to suggest stupid bands. The thing is; it’s hard; it gets harder as you go on, to kind of get curators to make you kind of fresh each time. I think because it’s a different curator each time, in a way, it’s a different person’s interpretation of a mixtape. If you get similar artists doing it, then you’re going to get the same sort of bands. We’re always striving to look for new and different ways to present it, to get different curators. It does get harder as you go on, but we’ve been pretty fortunate to be able to present some great things over the last 10 years.

Did you expect to reach your 10th birthday?

No. I’ve been waiting for the call to get a real job for quite a while now. When we did Bowlie Weekender with Belle & Sebastian [in 1999], they called it the first annual Bowlie Weekender and the idea was to do it year in, and year out. I don’t know why but they felt they wanted to keep the event unique and I said with their blessing, could I continue it and rename it, All Tomorrow’s Parties. I never thought it would go this long.

I think we’ve been fortunate that it is still strong and people still want to go to it, but I think we spend so much time laboring over things like artwork design, the programs to present, and the lineup and where bands play. We’re conscious of what the fans want, as well. We’re trying to make people happy so that they keep coming back. So far, I think we’re doing a good job.

I saw in an interview you said, “The way forward for festivals is to keep it boutique.”

Yeah, totally. You get some festivals like Bestival and they have the audacity to call themselves boutique when they started at 10,000 [capacity]. That’s not boutique for starters, and also I don’t understand why Rob Da Bank puts “Curated by” on each event. If it’s the same person doing it, surely, isn’t he the festival booker and that’s his job? You don’t need to wear a badge and put it on the top of the poster.

You’re talking about British festivals here, which I’m not too familiar with…

Oh, sorry – okay. Talking about boutique festivals, there’s one here called Bestival. It’s run by a [BBC] Radio 1 DJ called Rob Da Bank. The thing is, a lot of these festivals start at 3,000-4,000 capacity and then they start expanding. Because it’s only one event, they get bigger and bigger. Most of them have gone from 5,000 up to 45,000 or 50,000. It loses its intimacy and it loses track of where it started and why it started.

I think with us, it’s that we are keeping it sort of personal to people. It’s not overcrowded and you can walk around between stages and see lots of really great bands. I’d rather do more ATPs and keep it small, than do one big one and do it once a year because I just feel like it will lose its charm.

So the events here at Butlins are capped?

Yeah, the place only holds just over 6,000 so we sell 5,500 and the rest is made up of guests and production. It’s capped because that’s the legal capacity.

I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].

I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].

That was really great. There was some view up there, wasn’t it?

Yeah. And I went to the Riverstage one in Brisbane, which is where I live, as well as one of the Brisbane Powerhouse shows.

Okay. Those were good events, Buller especially. In hindsight I think I would love to have just done Buller. Those other events that we did… They were All Tomorrow’s Parties in the mindset but they weren’t like the All Tomorrow’s Parties because it wasn’t like a residential thing where people stayed, hanging out like they did at Buller. They were good, but I think it was a bit misrepresented in a way.

Now that you mention it, it’s quite odd that you did those Sydney and Brisbane events because like you mentioned, there was no accommodation. Do you put on many of those here in Britain?

No, to be honest; we’ve talked about doing a sister event called ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’, which is the b-side to The Velvet Undergrounds single ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’. The idea is that it’s like a sister event to ATP. It has the concept of the curator and stuff, but it doesn’t have the holiday camp. The idea of it is that it’s not trying to compete with ATP, it’s kind of designed for people to see great music but at a lower price because they don’t have to pay for their accommodation. There are a lot of people that would love to come to this but can’t necessarily afford it. It’s not that we’re too expensive; we’re providing value for money, but it’s a rising cost because Butlins is not a cheap place to hire.

I can imagine. As well as the festival aspect of ATP, it’s also a label. Again, what factors do you think have contributed to the success of ATP as a brand?

Someone said to me the other day, “oh, Fuck Buttons must be doing really well because the festival is doing well”. It’s not like that. There are a lot of records that we put out, and they’re releases that don’t necessarily sell a great deal. They’re great records, but the festival helps in the way that we can showcase the bands as another outlet for people to discover them. But bands like Fuck Buttons have done really well because they’ve made great records. Whether it’s on ATP or another label, I don’t think it makes any difference.

We’ve got a brand, not in the sense of Coca Cola or McDonalds, but I think a kind of brand of quality. I wanted it to be where you used to buy Sub Pop singles and you didn’t know some of the bands but you bought them because – I’m not saying you, here – but when Sub Pop was in its Nirvana and Mudhoney heyday – not that it doesn’t put great records out now – but there was a period when Sub Pop was releasing something you’d buy it because it’s like “Fuck, it’s on Sub Pop.”

Or Def Jam [Recordings] There were all those great early hip hop records like LL Cool J and Public Enemy, and Beastie Boys, and Run DMC. You knew that Def Jam and Sub Pop put out great things so you kind of bought into that. I feel like ATP is getting a bit like that in a way that people are sort of willing to take a chance because they know we’re not going to put out Coldplay or Miley Cyrus records.

You like ripping on Coldplay.

There are worse bands than Coldplay. [laughs] They’ve got a couple of good songs. I don’t think they’re for me.

Neither me. An aspect of the festival that I really liked, and I’m sure you do too, is the discovery aspect. As you say, it’s associated with quality. You walk into a room and at least respect a band, if not find it really damn good and want to go and buy all their shit.

Yeah. The reason we say it’s like a mix tape is you know, if you’ve got a friend and – I don’t know if you’ve ever had friends who give you mixtapes – but you put it on and you’re like, “Jesus, what’s this? This is great.” You have to look up the track list and you go, “This is amazing” but because you’re here at the festival and you’ve bought your ticket for the weekend, you can go in and out of rooms; there’s going to be something on you’ve never heard of, or you’ve been curious to know what it’s about.

It forces you to go and check stuff out, and it opens you up to loads of stuff. I think bands like Deerhoof, their success in Europe has benefited from playing at ATP. They said this themselves; they’ve been playing at an event and people have never heard of them before just a few years ago, and then they’ll see them and go, “My God, they’re great.” They’ll want to keep going back and seeing them. They’ve discovered it in that mixtape fashion, where it’s like a pleasant surprise.

I saw in an interview that you mentioned Kevin Shields [of My Bloody Valentine, pictured right] is fond of ATP because you kind of sidestep the whole music industry game.

I saw in an interview that you mentioned Kevin Shields [of My Bloody Valentine, pictured right] is fond of ATP because you kind of sidestep the whole music industry game.

Kevin’s been very supportive of us, and I think it would be fair to say we’ve done things in a different way. It’s good having a curator because it means we have to pick the bands the curator wants instead of agents, magazines, and labels all going, “You must put this band on because they’re the hot new thing”. It bypasses all that and we’ve just done things on our own terms.

To have a festival with no sponsorship, there is another promoter who asked me about doing an event in a holiday camp, and he said, “How the fuck do you do it without sponsorship?” We know how to do it because we’ve fine-tuned it over the years. We know how much it costs, how much we spend on bands, and it does make money but probably not the sort of money that some of the people out there think it does. Anything we have done goes back into the business.

I just feel like I want to keep doing this sort of thing until we lose interest in it. When we do lose interest, I think that’s the time to stop and end it on a high rather than fizzle out. The music industry is changing constantly, and I think it would be fair to say we never really played the games that a lot of people do. I’m not into that, so we just do our own thing, really. I guess we have sidestepped a lot of it, which is good.

You began as a promoter at Dingwalls [in Camden], and you got tired of having to play the game. Did you find it difficult to step outside of that and say, “Fuck it, I’ll do my own thing”?

Yeah, it was really hard because in those days, if a band like Tortoise came along, it was once every 6 months or something and it was a real big deal. Nowadays, if you open up Time Out in London or anything else, it’s like there are 100 bands on par with Tortoise that are playing constantly. There wasn’t really an outlet for that type of music I wanted to work with.

I found it was really hard because you would take punts on shows and the attendance would be down. You’d lose money and then it would be ages before another band that was worth doing comes through. It was difficult and also, it was tempting to try and go outside of that and start playing the game, but we rode out the rough times and kept it true to the original thing.

I’m supposing a big part of that is having the connections you made through ATP, such as Sonic Youth and the credibility that having guys like that playing in your festival lends you as a promoter.

That’s definitely helped, but the thing with us is that the roster of bands that we do outside of the festival are all bands that we actually like. I’ve been offered some bands that are huge and I’m like “I can’t do that.” I got begged to do Snow Patrol in 2003, and I remember their agent at the time was like, “I really want you to do it. They’re going to be great. They’re going to be massive.” I was like, “There is no way they’re going to be massive,” but the thing is; I didn’t know they changed their sound from sounding like Sebadoh to Coldplay. I think it’s good that we haven’t sold out in that way.

How do you go about goal setting for ATP? When you began, did you imagine 5 years down the track, 10 years down the track?

No, I have to be honest with you; every time I do the next one, I’m thinking about how it has to be better than the last one. We have to finally think of a curator that no one else is going for, and I want each one to be better than the last one. Some of them are fantastic and some aren’t as good as the others and it can be a bit disappointing, but I think we’re always striving.

Someone said to me today, “Do you think you’ll get to 20 years?” I’m like, “I don’t know, maybe.” I don’t know if I can think that far ahead, but as I said to you; I want to keep doing this as long as it’s still fresh and exciting, and the minute it stops being that, that’s the time to pull the plug.

When’s the next Australian ATP event planned?

That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.”

That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.”

ATP Australia – would it happen again? Yeah, we’d like to think so. We’re taking a step back because we’ve just got some venue issues and stuff. Once we resolve them we’d definitely like to pursue Buller again if we could.

Everyone I spoke to at Buller was just having a great time. Everything I read about it afterwards was extremely positive. Do you ever receive bad reports about ATP?

Yeah, for example I know some people came last weekend. We had My Bloody Valentine curating. Some people thought it was great but some felt the people there, the atmosphere wasn’t like it was at this one. I think each one changes by the crowd. There seemed to be quite a lot of middle-aged men last weekend, but there are lots of young girls at this one, which is always definitely more encouraging.

We do get some people who don’t think it’s – they’re not into it, but I think ATP – it’s what you make of it as well. You can be into the media but you’ve got to go there with a right mindset. You have to go there and want to enjoy yourself and let go and jump away from your job for 3 days and just embrace all the music and film, and the art, and hanging out with friends. It can be a really great thing to go to. Someone said to me, “Would you go to it yourself if you weren’t putting it on?” I’m like, “Yeah, I probably would.”

Probably?

Yeah, well I would, of course I would. I would. Sorry!

You mentioned events like Glastonbury and Reading and so forth, when comparing ATP. When was the last time you went to Reading and Glastonbury? Do you ever go to those events just to remind yourself?

I don’t compare ourselves. I use that as a reason why I started this. I went to Glastonbury in 2002. I will never go back to that thing. I just don’t understand how people could enjoy being there with too many people, too short of a space of time, and I’ve seen people – we were talking to Keith Cameron just now from Mojo. He was saying he saw someone get their head kicked in, in broad daylight there. There is a horrible vibe there, really.

It’s been a while since I’ve been to those; too busy running this. That was the only thing you could go to if you wanted to go see some of the bands. If the Pixies were over [playing shows], if you couldn’t see them in shows you went and saw them in Reading or Glastonbury and it was kind of like that was where you could see some of the rare bands you wanted to check out. It was more a case of using that as an example of where you would see that music and why we started this.

You mentioned that self control is important when booking bands, or when the curator asks to book bands. I’m taking it since the capacity is capped here, so is the budget for booking bands?

Yeah.

Is it difficult to manage?

If you gave me a wish list and you put AC/DC, Leonard Cohen, and Motorhead on there, then if you took one of those bands, it would just wipe out the budget. You need to kind of tailor the lineup to the size of the event. It’s always good to have a couple of big names and stuff, but I think the real beauty of ATP is having all those kind of midrange bands, the sort of ones that would fill up Center Stage and have – it’s better to have more of those midrange than all big hitters.

There have been a couple of events where we’ve had some really big names, and then it’s all been small bands, and it hasn’t felt balanced. You get lots of people at one show and then it’s kind of half empty at other ones. With the curators, I have to kind of say as much as we’d love to have Neil Young, as much as we’d love to have Bob Dylan, it’s probably unrealistic that we could afford it. We just kind of need to guide them, really. I try to give everyone as much freedom as possible. I’m just hoping no one puts Blur on their list. [laughs]

Is your favourite ATP still the Dirty Three-curated one?

Yes, definitely.

Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that?

Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that?

All the time. He’s just been so amazing to work with over the years, so supportive. There are other curators as well. There are so many of them I think of that was as well, but their whole take on it and the way they approached it and the actual weekend itself was just magical; it really was. I just was walking around and everyone was having the time of their life. I also thought that ATP that Nick Cave did in Mt. Buller was one of my favorite ones as well. Definitely, that was a highlight.

This one might be difficult to answer, but when you think of the average ATP fan or concertgoer, what image do you have in mind?

Someone who is into music, who probably is the sort of person that when they buy records, they want to know where the band recorded it, what studio, and stuff like that. Someone said to me, “record nerd” but I think it’s people who actually give a shit about music. They don’t buy their CDs or vinyl in supermarkets, which seems to be one of the few places you can buy music these days like that. Most of the record shops are closing.

So you’d say it’s for the more discerning music enthusiast?

Definitely. It’s for people who went to see bands that blew their mind and wanted to even start a band or get into music, where music is really special to them and they listen to it all the time, checking out new stuff and they’ve got memories of old things. I think ATP appeals to them because it crosses a lot of those things, really.

Do you try to avoid associating ATP with indie rock, in particular?

I guess I’m an indie kid at heart. I guess we’ve been described as an indie festival, but indie is a bit of a weird term these days. You get some people who are on indie labels but they have the mindset of a corporate sort of thing. We have had a lot of indie guitar stuff over the course of time, but the curators we pick, it’s the music they’re into. Each one is different.

For example, that Mike Patton one we did with The Melvins, that was pretty eclectic because it had Taraf de Haidouks and then you had White Noise and Stockhausen and those sort of things, but you also had Mastodon and The Melvins. It was very different. I guess most of the best music around is coming from indie labels. That’s why we focus on it really, but we get criticized for having too many American bands. Someone said that but I just think a lot of the bands that come right out of England aren’t very good. There are some good ones, but on the whole, I think a lot of the best stuff around has been coming out of the States for a while.

What’s your favorite ATP festival moment, ever, stepping outside of the office and just walking around, watching the bands?

There are way too many to remember…

I know you’re a big fan of Lightning Bolt [pictured left].

I know you’re a big fan of Lightning Bolt [pictured left].

I remember the first time that Lightning Bolt came and played ATP. There were a lot of people that didn’t know who they were and then when they played on the floor and the actual great thing was seeing the reaction on peoples’ faces. They were like, “What the fuck is this?” That was really good. There are so many.

I think some of the best things I’ve seen, music wise, is Sleep performed ‘Holy Mountain’ earlier this year. The Boredoms did ‘Boardrum’ in New York. That’s some of the best things I’ve ever seen at the festival but I think highlights for me are things like Slint, because ‘Spiderland’ is probably one of my favorite records of all time. Getting to see them perform that live was… I had to move a few mountains to get those guys back together.

I was saying to David Pajo today that when I met them, Slint had never been in a room together, the 4 of them, for 13 years. I’m a huge Slint fan and I said to them – we went to Britt [Walford]’s house for this meeting. I was so excited I was there and I said to them, “Can I go to the toilet?” They were like, “Yeah” and I was in there – I didn’t actually need to go to the toilet. I was in behind the toilet door going like this, “Yes!!!” just freaking out. I told David today and he’s like, “Really?” and I’m like “Yeah!” [laughs]

It meant the world to me. As I’ve said to some people, it’s like – the way [music magazine] Mojo think about The Beatles, I think about Slint. It was really special to see that and to see them perform because they were someone I always wanted to see and never thought I would because they weren’t together. That always sticks in my mind as a real special thing. I feel proud that we’ve done them, really.

The same kind of thing with My Bloody Valentine, too. You were kind of one of the forces behind them getting back together.

Yeah, they hadn’t been together for 16 years and the thing is; a lot of people have made them offers over the years, but it’s like trying to lift an old truck from a swamp, trying to get it back into motion. It was possible but it needed help. I think we were able to present them the setup they needed to do it. Kevin was really kind to trust us to do that. We did it. The shows were fantastic and it worked really well.

I just think we look at things in a different way. Some people promote like, “You’ll make this much money,” but you need to sort of show the artist what they’re going to get from it, not just the money. It’s got to be the actual performance and what benefit they get from it too. I think that’s important and that gets overlooked by some people. That’s probably why we’ve got to work with so many great artists over the years because of our attention to detail. We put care into it.

I saw them all three nights, last weekend. I’m so glad I did. It was one of the most amazing things I’ve seen.

Had you seen them before?

No. It was cool to see ‘You Made Me Realise‘ three times. [Notably, because the band end the song with a 15ish minute noise jam known as the ‘holocaust section’. It’s fucking intense.]

Did you have ear plugs in?

Of course.

I don’t know how they felt about the first show they did for us as warm-up show, at the ICA. I don’t think they were too into it, but the first time seeing those tracks being played live for a long time was like, “Whoa, this is going to be a joke.” When they went into a bigger room like the Round House and had the full PA, it was like a jet plane taking off.

What’s next for ATP? How do you go about planning for the next couple of years?

I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator] Matt Groening in May. Then I’m pursuing two curators for Christmas next year. I can’t say who they are just yet, but once I get them in place I’ve kind of got an idea of – we’ve had at least talks and I’ve got an idea of who they would want. I think it will surprise people because if both of them come off it will be things that people won’t be expecting. Again, we want to make is special because it’s the 10th year and we want to do the year-long celebrations and stuff.

I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator] Matt Groening in May. Then I’m pursuing two curators for Christmas next year. I can’t say who they are just yet, but once I get them in place I’ve kind of got an idea of – we’ve had at least talks and I’ve got an idea of who they would want. I think it will surprise people because if both of them come off it will be things that people won’t be expecting. Again, we want to make is special because it’s the 10th year and we want to do the year-long celebrations and stuff.

You had the ATP film for the 10th anniversary, which I saw in my chalet the other day. Any plans for a book?

There has been talk of it. We were talking about maybe doing a kind of book, incorporating the artwork and stuff. Yeah, we’ve been approached by people to do it, so you never know… “You bought the t-shirt, you watched the film, now read the book!”

I’m sure there’s a market for it. ATP fans are pretty hardcore.

They are, but the thing is they’re not stupid. I couldn’t just put on a crap lineup because then people won’t come. It needs to be quality and people actually sit on the fence saying, “I’m thinking of going to this one but if they announce a couple of more bands” and then they do, but my favorite thing is watching kids on message boards, and I’ll be looking at various things because it’s always good to see what people are up to or saying. They’re always like, “Why the fuck did they get them to curate? They’re going to pick a load of shit!” and I remember when they did that with Mars Volta and Explosions In The Sky and then the same people 6 months later were going, “This is the best lineup ever. I’m totally going.” During all this time it was like, have patience. You need to see it unravel itself and I think it’s kind of good doing that because we know what’s coming and seeing the reaction from people is good.

Do you keep an eye on the feedback and reviews from attendees afterwards?

We do, we take things on board. If someone says I had a really shit time in this venue because of something like the lights might be wrong or the PA was in the wrong place, we don’t ignore that sort of thing. We take it on board and try and make each one better than the last one, like a new and improved formula each time we do it.

There are a few people here that haven’t been here since 2007 and the Pavilion Stage, which is the big room, we didn’t have those drapes down the side, and we didn’t have the star cloth. They make a massive difference to that room. We also changed the PA in the Center Stage where you were for My Bloody Valentine. Just lighting configurations and things like that but it’s all – we use feedback and we exploit it and make put it to use in a beneficial sense so that each time someone comes back they go, “Oh, this is fixed up.”

Better and better.

Yeah, if you rest on your laurels and go, “Oh yeah, we’ve got this great thing now and got the curator in, that’s it. You’ll fucking like it or lump it” then it won’t last another 10 years. Whether I’m still doing it in 10 years is another thing but I only want to keep doing it until I lose the fire inside me that started it.  There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good.

There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good.

You went to last weekend. I didn’t feel that same atmosphere last weekend as I did at this one. Again, it’s like a different mix tape and a different interpretation. It was quite abrasive last weekend, the music and stuff. It was all that heavy guitar stuff. It was good, and it worked really well, but I think this one seemed to be a bit more eclectic.

Thanks for your time, Barry.

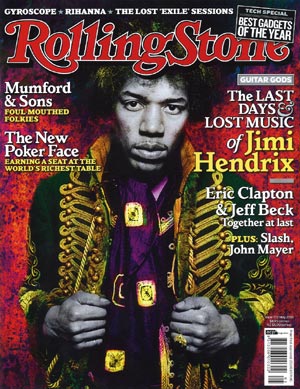

This interview was conducted for a story on behalf of Rolling Stone Australia, pictured left. Read that story here.

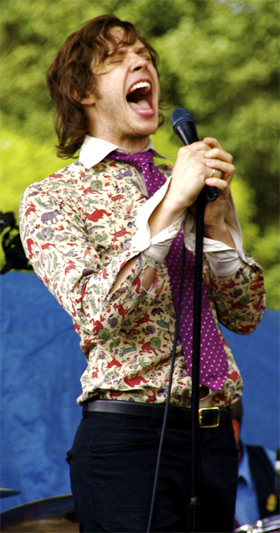

OK Go are an American pop band. I don’t want to cheapen their career by naming just its apex, but it’s the easiest way to refresh your memory: they’re the band behind ‘Here It Goes Again‘, better known as ‘the treadmill video‘.

OK Go are an American pop band. I don’t want to cheapen their career by naming just its apex, but it’s the easiest way to refresh your memory: they’re the band behind ‘Here It Goes Again‘, better known as ‘the treadmill video‘. We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world.

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world. Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think.

Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think. First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it. My first cautionary tale as a print media journalist: a lot can happen in the time between submitting a story, and the magazine going to print.

My first cautionary tale as a print media journalist: a lot can happen in the time between submitting a story, and the magazine going to print.

In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks.

In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks.  I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].

I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].  I saw in an

I saw in an  That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.”

That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.” Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that?

Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that? I know you’re a big fan of

I know you’re a big fan of  I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator]

I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator]  There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good.

There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good.

Hogan worked on the Belle and Sebastian-curated Bowlie Weekender in 1999. ATP – named after a 1966 Velvet Underground song – is based on Bowlie’s artist-as-curator concept. The festival ventured to Australia in January 2009, featuring a centrepiece weekend event at the off-season Mount Buller Ski Resort; day shows in Brisbane and Sydney followed. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds were the inaugural Australian curators.

Hogan worked on the Belle and Sebastian-curated Bowlie Weekender in 1999. ATP – named after a 1966 Velvet Underground song – is based on Bowlie’s artist-as-curator concept. The festival ventured to Australia in January 2009, featuring a centrepiece weekend event at the off-season Mount Buller Ski Resort; day shows in Brisbane and Sydney followed. Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds were the inaugural Australian curators. I

I

Until recently I was working as a part-time freelance illustrator, but have since joined a commercial illustration agency and heading towards full-time client work.

Until recently I was working as a part-time freelance illustrator, but have since joined a commercial illustration agency and heading towards full-time client work.

No, that’s not correct. I think what happened with

No, that’s not correct. I think what happened with  I just think it’s about options. There was a lot of feedback online about how people don’t stream music to the PC and people would never use it. If you look at

I just think it’s about options. There was a lot of feedback online about how people don’t stream music to the PC and people would never use it. If you look at  No, not really. To be honest, when we launched Bandit in November, Spotify was on the radar and probably has significantly upped its profile in the last twelve months. Bandit’s plan was always to have a subscription service operating around October/November of this year.

No, not really. To be honest, when we launched Bandit in November, Spotify was on the radar and probably has significantly upped its profile in the last twelve months. Bandit’s plan was always to have a subscription service operating around October/November of this year. We’ve got our own editorial team that puts together news stories, and also looks after Bandit on

We’ve got our own editorial team that puts together news stories, and also looks after Bandit on  The other thing that we’ll be adding in October is a level of social networking, which will be quite interesting. In that case, the core part about Bandit is the channels. You can see different

The other thing that we’ll be adding in October is a level of social networking, which will be quite interesting. In that case, the core part about Bandit is the channels. You can see different  My

My

In August 2009, a service called

In August 2009, a service called

It would be good to get perspective on it that wasn’t just from Sony – the main thing is this can’t be a PR piece for them. A non-Sony artist who will be for sale there is good, maybe a comment from someone at one of the other majors. Nokia also do a subscription of sorts, so maybe that’s something to consider…

It would be good to get perspective on it that wasn’t just from Sony – the main thing is this can’t be a PR piece for them. A non-Sony artist who will be for sale there is good, maybe a comment from someone at one of the other majors. Nokia also do a subscription of sorts, so maybe that’s something to consider…