Two books reviewed for The Weekend Australian in a single article, which is republished below in its entirety.

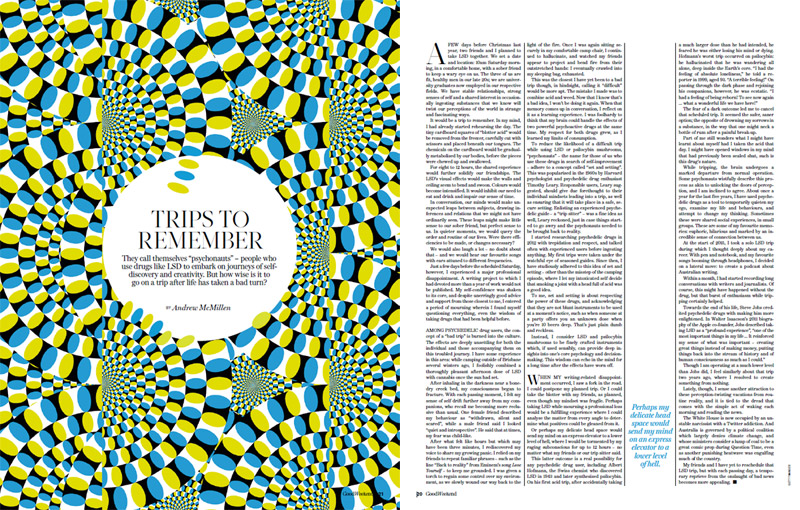

Sex and drugs and on a roll

Genuine candour is one of the most difficult emotions to capture in any form of human communication, writing included. There seems little point in committing to write a memoir if not to tell the whole truth and nothing less.

Genuine candour is one of the most difficult emotions to capture in any form of human communication, writing included. There seems little point in committing to write a memoir if not to tell the whole truth and nothing less.

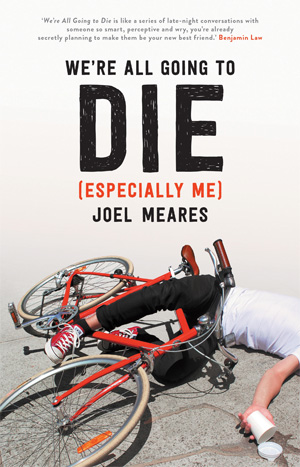

This is especially so for young writers, whose ambition and urgency to impress by sharing their innermost secrets has become something of a cliche in an era of online ‘‘oversharing’’. Walking the line between tiresome navel-gazing and insightful, rewarding revelations is tough, but with his debut book Sydney writer Joel Meares succeeds with style.

In his job as arts editor of The Sydney Morning Herald, 30-year-old Meares acts as a cultural gatekeeper, deciding who and what is worthy of coverage. In We’re All Going to Die, his astute editing skills are on display across 10 personal essays that illuminate his early life and formative experiences as a young adult. There are occasional asides to his professional career but, by and large, Meares uses the book as a vehicle to examine his intertwined paths as a writer, son, friend, horror-film enthusiast and gay man.

It is on this last path that he is at his strongest, through two central chapters that draw the book into stark focus. The first concerns Meares slowly coming to terms with his homosexuality in his 20s, after denying it constantly throughout his childhood and adolescence. One section, in particular, provoked a sharp intake of breath, when Meares writes that he denied his homosexuality because

I’m sad to say that these sentences rang true for me, as someone a few years younger than Meares who has only relatively recently become aware of the gravity of these types of insults. It is insights such as this for which We’re All Going to Die is strongly recommended, as Meares is clearly a man with something to say and ample ability with which to say it. The chapter that immediately follows, titled So Is Dad, concerns his father’s coming out and it is beautifully and sensitively written.

Elsewhere, Meares writes of his brief but intense enthusiasm for ecstasy and cocaine. “In Subway sandwich terms, I’ve never been a six-inch man — it’s always been a footlong or nothing,” he writes. “With jalapenos.” This dalliance culminates in panic attacks and several visits to the emergency room, capped with a stern warning from medical professionals that some people just can’t handle their drugs. “Drugs scared me once because they were ‘bad’; they scare me now because they are bad for me,” he concludes.

The essay on drug use is rooted in a feature story Meares wrote years ago about Sydney’s cocaine scene, and the same is true of his chapter on paruresis, or ‘‘bashful bladder’’ syndrome, which grew out of a 2012 article for Good Weekend magazine. In that story, Meares proved himself a willing comic foil for a serious topic by admitting he had long struggled to urinate anywhere but in a closed toilet cubicle. It’s fascinating, this psychological quirk that caused many men embarrassment and inner pain when faced with shared urinal situations, such as at music festivals, yet Meares handles it with good humour and grace.

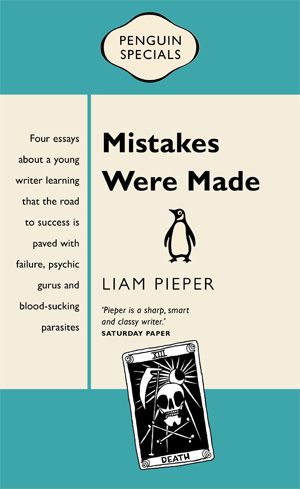

Slightly more embarrassing than being unable to piss in the presence of other men is the act of hugging a pony in northern NSW and unknowingly picking up a tick that burrows its way into the back of one’s skull, towards the brainstem, and breeds. This simple transaction — a hug for a tick — becomes near-fatal for Melbourne writer Liam Pieper, who contracted a bacterial infection that disabled the lymph nodes on one side of his body, partially paralysing him and coming dangerously close to entering his brain. This took place while Pieper was visiting the cannabis countercultural hub of Nimbin. He was on assignment as a freelance journalist, researching a story for an unnamed “Very Important Magazine”. He ended up filing a 15,000-word story that was three times longer than the magazine requested, written under the disorienting effects of the arachnid’s neurotoxins. The “tick-addled gibberish” was spiked by his editor and the writer nearly died.

Slightly more embarrassing than being unable to piss in the presence of other men is the act of hugging a pony in northern NSW and unknowingly picking up a tick that burrows its way into the back of one’s skull, towards the brainstem, and breeds. This simple transaction — a hug for a tick — becomes near-fatal for Melbourne writer Liam Pieper, who contracted a bacterial infection that disabled the lymph nodes on one side of his body, partially paralysing him and coming dangerously close to entering his brain. This took place while Pieper was visiting the cannabis countercultural hub of Nimbin. He was on assignment as a freelance journalist, researching a story for an unnamed “Very Important Magazine”. He ended up filing a 15,000-word story that was three times longer than the magazine requested, written under the disorienting effects of the arachnid’s neurotoxins. The “tick-addled gibberish” was spiked by his editor and the writer nearly died.

This sequence of events isn’t funny. Or at least it shouldn’t be. But the way Pieper contextualises it is very funny indeed. This opening essay, Catching the Spirit, is one of four that comprise Mistakes Were Made, a breezy and compelling read that exhibits Pieper’s hilarious, dark way of observing and interpreting the world around him.

The central narrative thread through these four stories is the writing, publication and promotion of Pieper’s memoir, The Feel-Good Hit of the Year, released last year, where he wrote about his experiences as a teenage drug dealer, including the time he sold cannabis to his parents. “What I didn’t understand then is that the first angle to a story to come out tends to be the one that stays around,” he writes. “My folks got a little pot off me once, and that would be the defining narrative of my life for the foreseeable future.”

With this little book, Pieper builds a strong case for redefining his narrative post-memoir: the other essays concern contrasting racial prejudices in Australia and the US, being stopped at Customs by Los Angeles airport and queried on his drug history, and his brief adoption of a dog named Idiot Geoffrey. His writing is electric: charged with meaning and energised by surprising comedic turns. Between Meares and Pieper, there’s not a trace of tiresome navel-gazing; instead, true candour abounds.

Andrew McMillen is a Brisbane-based freelance journalist and author of Talking Smack: Honest Conversations About Drugs.

We’re All Going to Die (Especially Me)

By Joel Meares

Black Inc, 210pp, $27.99

Mistakes Were Made

By Liam Pieper

Penguin Specials, 67pp, $9.99

Scottish-born journalist Jill Stark was a health reporter with a blind spot: despite writing about Australia’s binge-drinking culture for The Age newspaper, she would regularly drink to excess, as she’d done since her teens.

Scottish-born journalist Jill Stark was a health reporter with a blind spot: despite writing about Australia’s binge-drinking culture for The Age newspaper, she would regularly drink to excess, as she’d done since her teens. Proud and dodgy Dave Graney

Proud and dodgy Dave Graney