Click the below image to read as a PDF in a new window, or scroll down to read the article text.

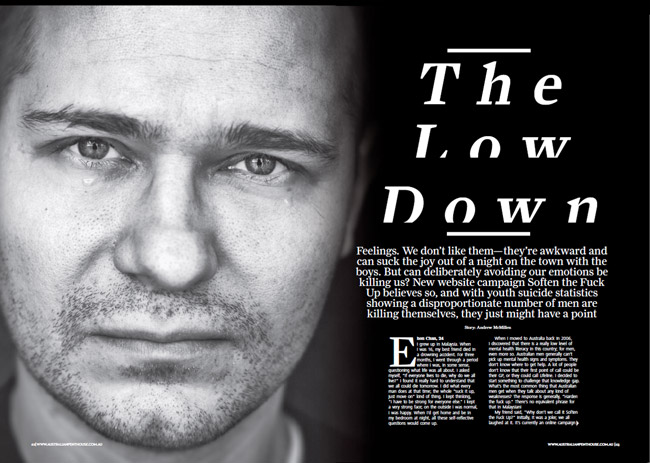

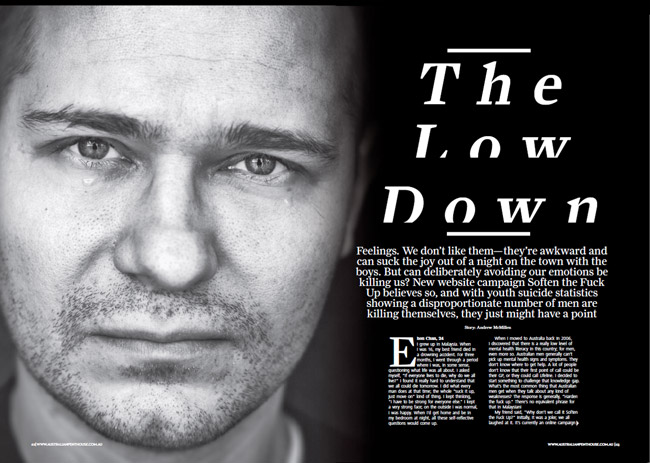

The Low Down

Feelings. We don’t like them – they’re awkward and can suck the joy out of a night on the town with the boys. But can deliberately avoiding our emotions be killing us? New website campaign Soften The Fuck Up believes so, and with youth suicide statistics showing a disproportionate number of men are killing themselves, they might just have a point.

Story: Andrew McMillen

++

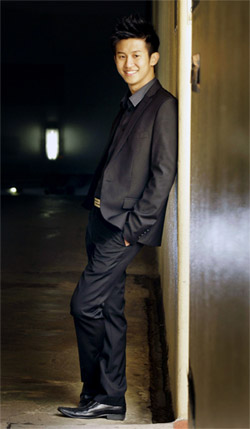

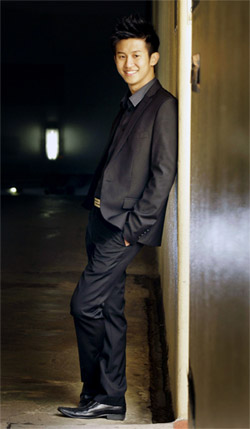

Ehon Chan, 24

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up.

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up.

When I moved Australia in 2006, I discovered that there is a really low level of mental health literacy in this country; for men, even moreso. Australian men generally can’t pick up mental health signs and symptoms. They don’t know where to get help. A lot of people don’t know that their first point of call could be their GP, or they could call Lifeline. I decided to start something to challenge that knowledge gap. What’s the most common thing that Australian men get when they talk about any kind of weaknesses? The response is generally, “Harden the fuck up.” There’s no equivalent phrase for that in Malaysian!

My friend said, “why don’t we call it Soften The Fuck Up?” Initially it was a joke; we all laughed at it. It’s currently an online campaign (softenthefckup.com.au, launched in July 2011), but we also want to make it an offline conversation. We want to take the conversation to the next level, so it’s not just about having a conversation with your mates, but equipping young people – in particular, men – with an idea of how to recognise signs and symptoms of mental health issues. And also, when someone comes up to you and says “I’ve got depression”, or “I haven’t been feeling well for the past five days”, what do you tell that person? What are the things you can and can’t say? Where do I get help?

I was hesitant when the name was first suggested, because the word ‘fuck’ was in there. I wasn’t comfortable going ahead with it, but the more we thought about it, the more we decided, “you know what? That’s the whole point of this campaign”. We want to be unapologetic, we want to be in your face, and we want to push the extreme because we really want to change the culture. The more extreme we go, the more conversation it’s going to generate.

++

Paul Klotz, 51

At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about.

At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about.

I’ve spent most of my life under the influence of drugs or alcohol to pretend that I was a normal, sane person. Despite that, I was extremely successful throughout my business career. But I’ve always lived with that self-destructive path. Once I achieved, I didn’t feel worthy. Because of this lack of self-esteem and self-belief, I was just continually and totally despising myself. Two years ago, I was able to look in the rear vision mirror, look at all those demons that had been there for the last 35-plus years and say, “enough’s enough; I need to deal with this”.

This decision came at a huge cost. It’s doubtful if I’ll work again in anything near the capacity that I was before, because I’ve withdrawn from society. I feel uncomfortable around people, moreso than I ever did. It’s great to finally confront those demons and understand and recognise that I’ve suffered from severe depression, and severe post-traumatic stress disorder. I see a psychiatrist. I’m on all sorts of drugs and pills to try and keep that balance of life.

In the last eight months I’ve been through five suicide attempts, and I’ve had to resign from the last two jobs because of the impact that my mental condition was having, and the episodes of depression, and being put into hospital. That started a period of living on the streets. I have nothing to hide. I’m quite comfortable in saying that if it wasn’t for my four beautiful boys, I wouldn’t be here. I have no doubt about that. During the last few suicide attempts, when I was fading away, it was the image of those guys that allowed me to get some strength, and fight back.

If I get through all of this, my burning ambition is to assist other males out there. I want to let other males know that it is okay to put your hand up, it is okay to cry. It is okay to say, “I have been abused”, as difficult as that is. It is okay to say, “I’m suffering from depression”. It is okay to say, “I feel suicidal”. I live with the thoughts of suicide every single day of my life. We need to break down all these stereotypes that my generation – and I suppose it continues on, of – “Harden up son. Big boys don’t cry. You’ve just gotta suck it in, and move on,” because that’s such a narrow-minded, dead-end approach. Those feelings of discomfort, unhappiness, pain, guilt, shame; if they’re left inside, they do fester, and fester badly.

++

Nick Backo, 23

I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”.

I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”.

It was hard to talk about. It brought up a lot of my own emotions, and you feel vulnerable sharing that sort of experience with people. It was also hard because a lot of people wouldn’t know what to say, or how to manage it. They were generally lost for words, so it was an awkward experience for me in bringing that up with them. To an extent, it’s something that you’ve got to live to understand. It would be beneficial for others to learn about grief, though. More broadly, it’s about educating people on supporting their mates, and being open to those types of conversations. Even if you don’t know what to say, just being there to listen and saying how you feel during those conversations is helpful.

It’s important to embrace the characteristics of masculinity. One of those is ‘being strong’, and it’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s also really important to talk about how you’re feeling, and your experiences. When Dad died, I was at that ‘coming of age’ stage in life. A lot of people were saying to me, “make sure you look after your Mum”, or “you’re the man of the house now”. I don’t think they were meaning it to put pressure on me. I guess it’s just what people say.

For people currently experiencing grief, I’d tell them that it’s OK to feel however you’re feeling. If you’re angry or upset, or if you’re feeling okay or happy, that’s all part of the experience of grief. It’s fine to have those emotions. I’d really encourage them to talk to people that they feel comfortable with, and to talk about their grief and the person who has died. Even if it seems a bit crazy or unusual, that’s OK, because it’s an unusual experience to go through. I think about Dad every day, but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned how to manage my grief better. I took away a lot of positives from it, as well. I think I’m a better person because of that experience. On the same hand, if I could change that and have Dad back, I would in a second.

++

Ben Pobjie, 32

I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist.

I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist.

When I’ve been at my worst, I’ve self-harmed. I’ve cut myself. It’s hard to explain after the event, when you’re not in that headspace, exactly why you did something like that. It’s a culmination of trying to distract yourself from an emotional pain by giving yourself some physical pain. It’s a confusing time because when you go through those episodes, because obviously you’re not thinking rationally, and you don’t react to your own feelings rationally.

When you’re depressed, you feel ashamed of yourself. It feels like something that you shouldn’t talk about. But I came to the realisation that if I didn’t tell people about it, then this can’t really be recognised as an illness. It couldn’t just be a secret that I kept. It takes courage to admit that you have a weakness. Everyone has weaknesses. It’s gutsy to own up to that. Most people are very willing to understand, and to show sympathy and support if it’s brought out into the open. That’s what I’ve found.

++

William Wander, 24

I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.

I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.

I hadn’t been on anti-depressants for years until the GFC hit. I lost my job, I was unemployed for the first time in my life. I applied for 250 jobs and couldn’t get a single one. I hit rock bottom. The thing about depression is: it’s a hole that you can’t get out yourself. I’ve spoken to a lot of people about depression, and I’ve never met anybody that’s got out of it by themselves. I don’t think it can happen, honestly. You need to have somebody else, or some other group that helps you get out. You can take the first step, obviously, and say “I need help”. But in the end, it’s the support of other people that helps you to get out of that, and start to feel better.

Depression is a disease that you can’t see. If you get hit by a car and your leg is twisted, that’s very visible and we can understand that. When people talk about depression, they feel weird about it for one of two reasons: they’re experienced it and they’re embarrassed about it and don’t know how to talk about it, or they have never experienced it and they can’t conceptualise it in their own head.

I don’t care who you are, or how in touch with your emotions you are; it’s never easy to admit that you’re depressed. It’s always difficult, because the nature of depression is that you don’t want to acknowledge it. It’s easy to talk about it now, but when I am actually depressed, it is hard to acknowledge that, even to myself. I’m a very emotional guy. At the same time, I’m a fairly typical Aussie bloke, but I’ve always thought it’s ridiculous how closed-up guys are in general in Australia. Let’s not skirt around the issue. Let’s be men about it. Which, ironically, means approaching something, rather than just avoiding it.

An enormous thanks to the brave men I interviewed for this story, and to Australian Penthouse for publishing.

If you are distressed after reading this story, please call Lifeline immediately on 13 11 14 (free call from all telephones in Australia).

I didn’t know this until I read The Boy Who Loved Apples, in which first-time author Amanda Webster takes on twin challenges: to write a confessional account of the most difficult time of her life and to educate readers about the complexities of an illness few understand intimately, especially as it applies to boys. She succeeds on both counts.

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up.

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up. At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about.

At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about. I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”.

I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”. I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist.

I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist. I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.

I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.