The Weekend Australian Review story: ‘Etched In Memory’, October 2015

A story for the October 31 issue of The Weekend Australian Review. The full story appears below.

Glenn Ainsworth’s art is an exercise in beauty, tragedy and catharsis

It was the night before the stillbirth of his son that Glenn Ainsworth realised he needed to sketch Baxter. He and his wife, Nichole Hamilton, were staying overnight in Buderim Hospital, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, in February last year. It was a Wednesday, and that morning the couple had been told Baxter had no heartbeat. They were offered sleeping pills, but both refused. Instead they lay together, numb with grief.

“We just both lay there all night, watching the bloody clock,” says Ainsworth , a softly spoken 38-year-old. “That’s when I knew what I wanted to do.”

Hamilton gave birth to Baxter on Thursday, February 13. “We were dead tired; we’d been awake for two days,” says Ainsworth . “I was just staring at him, trying to burn him into my head. You know that your time’s limited. You’re not going to see him after that day.”

At first Ainsworth chose not to tell Hamilton of his plans to sketch their son, but when he did, she wasn’t surprised. Art runs in Ainsworth’s blood. Inside the garage of their two-storey home at Peregian Beach is a studio where the civil engineer paints and sketches, honing a talent he first picked up between rugby league matches while growing up in Biloela, a rural town in central Queensland. With Baxter’s sudden death, the couple were ushered into an exclusive club that no one joins voluntarily.

“I thought stillbirth was something that only happened in Third World countries,” says Hamilton, 40, beside her husband of 10 years. “Nobody talks about it, and that makes it harder for friends and family to know what to say.”

In time, the couple found their way to Sands Queensland, an organisation that provides support to parents who have experienced miscarriage, stillbirth and newborn death. It wasn’t long before Ainsworth decided to offer his skills to those who had joined the club. “It just grew from there, I suppose,” he says. “I thought it might be a nice opportunity for other people: if they can’t do a sketch, I’ll do it for them.”

Says Nicole Ireland, president of Sands Queensland: “Glenn wanted to do something. He suggested that parents could make a donation to Sands, and he volunteered his skills to sketch their babies. A lot of people are more comfortable displaying drawings rather than photographs.” Parents can order a “free spirits” personalised portrait, hand-drawn by Ainsworth, based on supplied photographs. The proceeds go to the organisation, which is funded through Queensland Health’s community self-care program as well as via member donations. “(Glenn and Nichole) obviously have great support around them,” says Ireland, whose son Nicholas was stillborn 10 years ago. “But (Glenn would) have to balance his giving back with his grief.”

In the couple’s home, adjacent to the rooms downstairs where Hamilton runs her physiotherapy clinic, Ainsworth sits at his computer and opens a scanned copy of his sketch of Baxter. His eyes trace the soft curves of his baby boy’s face, hooded in a blanket, his tiny hands grasped together just so. “Some of them are quite difficult, because some of them are quite young in terms of the gestation period,” he says quietly. “A lot of the bubs get a bit bruised, and have skin tears and stuff like that, which is just awful. I look at the pictures, then don’t do anything for a couple of weeks. I just have a think about it.”

He starts with the face, making sure to get the proportions right before adding other details. Sometimes he draws composite sketches based on several photos. At the parents’ request, he can sketch around tubes and cords, thus removing their child from a medical context. He has completed 11 sketches so far, averaging one a month, and usually has another two or three waiting in the queue.

Moving across to a filing cabinet beside his workspace, he flicks through folders until he finds his original drawing of Baxter. He holds it carefully at the edges, silently taking in his priceless drawing of a boy who was gone too soon. In the shock that followed his stillbirth, neither parent considered taking a photograph of their son. Hamilton’s sister did, though, and in the months that followed those few photographs became the couple’s most important possessions. A framed copy of the sketch of Baxter hangs now in their bedroom. “I’m glad that Glenn’s art has a chance to help people,” says Hamilton. “It’s a beautiful thing to share. I love his drawing of Baxter.”

When asked how long each drawing takes to complete, he laughs and replies: “Put it this way: on an hourly rate, I’d be on about 20c an hour.” But it’s not about money.

Ainsworth tends to lose track of time down in the quiet of his studio, with performers such as David Gray, Lady Antebellum and Amos Lee playing softly from the speakers. He sketches with a range of pencil grades and isn’t picky about brands or styles, opting to buy whatever the local art shop happens to have in stock. He is a self-taught artist, and doesn’t pay much attention to the work of contemporary professionals, though he is particularly fond of a New Zealand landscape artist named Tim Wilson.

The grieving process hasn’t been easy. Hamilton says that for the first year, she cried every day. Ainsworth’s experience was much the same. “I’d get in my car each morning and cry all the way to work, and on the way home, 40 minutes each way,” he says. “I burst into tears all the time now.”

Talking about the experience in his home with a stranger isn’t easy, either. Hanging on the wall of his living room are some of Ainsworth’s artworks, including photorealistic paintings of a sea turtle and clownfish. “You’ve got everything ready to bring a baby home. You go from the highest feeling to the lowest,” he says. “I’m just climbing out now, after 18 months.”

Losing Baxter has made the couple stronger. “It’s welded us together,” says Hamilton, smiling at her husband. “I couldn’t have survived it without Glenn’s hugs and help.”

The father still experiences the odd moment where the memory of his son hits him like a punch to the sternum, prompting him to ask himself: Holy shit, did that happen? They both find it hard to hear other parents making complaints about their children.

“To hear your baby cry, you’d give anything,” says Ainsworth.

About 106,000 couples experience reproductive loss each year, yet it remains a difficult topic of conversation. Indeed, Ainsworth and Hamilton are highly attuned to how uncomfortable this topic can be. When new patients arrive at her clinic and ask whether she has kids, there’s now a moment of hesitation as Hamilton measures whether to tell the truth. It’s much easier to talk about a dead grandparent than a dead son. “It’s not our discomfort anymore, it’s theirs,” she says.

Since that February day last year, the couple has learned a few things about how to best support bereaved parents. Just be there. Be an ear. Sometimes a hug is the best response. Ask the parents: What was the child’s name?

For the artist, his is a project wrapped in beauty and pain.

“It’s something to immerse myself in,” says Ainsworth, returning to the computer and showing some of the other baby boys and girls he has drawn. “It’s this little guy’s birthday next week, I think.”

He pauses. “It’s an awful thing: no one should ever have to bury their child, irrespective of age. With stillborns, you don’t get to share any of those memories. I do these sketches for my sanity.”

For more about Sands Queensland, visit sandsqld.com

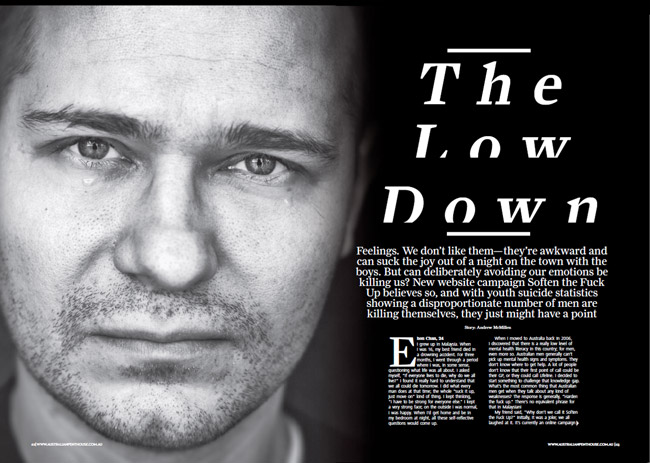

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up.

I grew up in Malaysia. When I was 16, my best friend died in a drowning accident. For three months, I went through a period where I was, in some sense, questioning what life was all about. I asked myself, “If everyone lives to die, why do we all live?” I found it really hard to understand that we all could die tomorrow. I did what every man does at that time; the whole “suck it up, just move on,” kind of thing. I kept thinking, “I have to be strong for everyone else”. I kept a very strong face; on the outside I was normal, I was happy. When I’d get home and be in my bedroom at night, all these self-reflective questions would come up. At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about.

At the age of 13, I suffered sexual and physical abuse at the hands of the Catholic boarding system in Brisbane. After many months of being abused in every form you could imagine, I was then beaten with a leather strap for being a ‘bad boy’. After 36 years of hiding in a false existence and having to support a facade of a personality, I finally collapsed, and all of my defences began to crumble. I told a very select group; immediate family, my psychiatrist, and a few other friends. They were shocked, angry, and frustrated in terms of not knowing all these years. It’s not something that was easy to talk about. I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”.

I’ve lived in the same house in Parramatta all my life. I’m a social worker for child protection services, as well as studying post-graduate psychology and refereeing soccer. When I was 15, my Dad died. There was a lot of shock initially, because his death was unexpected. I became the eldest male in the house. I felt that I had to be strong, and look after my family. I saw a counsellor for two years, on and off, which was really useful for just talking with someone who was neutral, and who could give me some strategies around managing grief. I had a lot of support from friends, who gave me someone to talk to, even if it was just, “hey, I’m feeling shit”. I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist.

I only recognised this year that I am suffering an illness. Since I was a teenager I’ve suffered periodical depression; I’d sink into a deep low for no particular reason. In the past I’ve been advised by people close to me that I should seek counselling. I’d shrug it off, saying “no, no, I’m just sad. Just going through a bad patch.” Which is not the right thing to do, really. You try and fight through it, because I didn’t want to appear weak or like I was making a big fuss over nothing. It builds up and gets worse and worse, and you have to admit that it’s not nothing. I broke down early this year, then realised that it’s not normal. I generally write jokes, and comedy. I’ve been writing more serious reflective things, having admitted to this. It’s possibly made me a little bit more honest as a writer. I’m on medication now, and I’m seeing a therapist. I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.

I’m Brisbane born and bred. I went through various Catholic schools, though I’m definitely not Catholic. I work in sales for a software company. By night, I’m a writer and blogger. I’m that guy in their group of friends who always says the things that nobody really wants to hear. I’m a little bit too honest. I’ve always had something to do with depression, even from the age of 11 or 12. I had a very rough childhood; I had an abusive father, and was quite sick as well, while growing up. From the age of 13 or 14, I was on anti-depressants. For me, having depression is like having asthma; it’s just part of your genetic makeup, and you learn how to appropriately deal with it.