A Conversation With Mikey Young, Eddy Current Suppression Ring guitarist

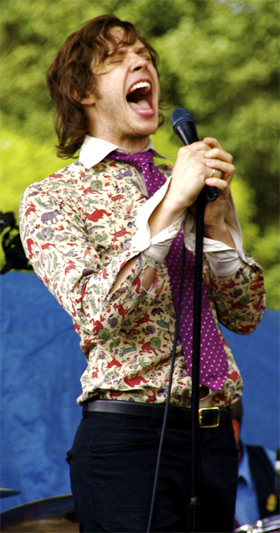

Eddy Current Suppression Ring are a Melbourne garage rock band. I spoke with their guitarist, Mikey Young [pictured right], for a story in The Big Issue (‘Keeping Current‘) that was published in late April 2010. Our conversation took place on March 17, ahead of a national tour in support of their third album, Rush To Relax. What follows is a transcript of our whole conversation.

Eddy Current Suppression Ring are a Melbourne garage rock band. I spoke with their guitarist, Mikey Young [pictured right], for a story in The Big Issue (‘Keeping Current‘) that was published in late April 2010. Our conversation took place on March 17, ahead of a national tour in support of their third album, Rush To Relax. What follows is a transcript of our whole conversation.

Andrew: Mikey, my first question is more of a statement than a question. It’s something that I’ve noticed. Eddy Current seem to be one of the best bands in Australia at deflecting any and all praise thrown your way.

Mikey: Well I appreciate praise, but it makes me really uncomfortable. I’m glad people like us, for sure, but I’m very wary of not letting praise go to our heads or thinking about it much.

So it’s not a matter of when you’re nominated for a new award or critical accolade, you don’t sit down together and go, “Right, what’s the best way to downplay this?”

No, not at all. I’m usually the one doing the interviews and so it’s probably my reactions that appear [in the media]. I don’t want to come across… I’m sure that quietly in my head I’m stoked and we’re proud of ourselves, but we definitely don’t sit around and say “let’s downplay it”. And the opposite of that, we don’t sit around going “how good are we?!”, slapping ourselves on the back. Awards and stuff are funny anyway, they’re a strange concept. We try not to think about it, and just make some tunes.

A broad question: why do you think people like your band?

That’s another thing I’ve briefly thought about in the past and I realised the more I think about it, actually I don’t really want to think about it. I don’t really want to know why people… I don’t want to be conscious of that. I feel it might sort of affect how we make music. If I’m oblivious to it and we just do it, for ourselves, then I figure it will be easier on my head.

I have thought about it, though. I think we’re a good live band, which helps. I think there is a fair simplicity to the music, and honesty in Brendan’s delivery and lyrics. I guess when things are really simple and honest upfront, then maybe they appeal to a larger range of people. I don’t know. I think to keep things pretty simple, then a lot of people can get into it. That’s not why we make simple music. I guess that’s just the way it turned out, but if I had to think about why people like us, hopefully it’s because we’re an okay band.

Do you think a band’s talent is reflected in their number of fans or number of records sold?

Are you asking whether popularity is representative of talent? Not always, I would think not. Seeing as I can barely listen to the radio these days, but that’s just my opinion. I just can’t stand a lot of popular music. That doesn’t really mean they’re talentless. I’m sure there is talent in making songs that I consider horrible to my ears; it just doesn’t work for me. I feel out of the loop when it comes to popular music at the moment. I’m probably not the best person to ask that question. Popularity and talent aren’t always on the same page.

Reading your past interviews, I did notice that the recurring theme of refusing to self-promote…

I have to stop doing all these interviews. I have all the same answers. [laughs]

There’s a quote of yours that I like: “I think if you don’t shove yourself in peoples’ faces, they’ll end up liking you more in the long run.”

I guess that was – maybe not from the start because we probably didn’t think that far ahead, but when we realised things were starting to have some sort of groundswell of popularity, that was something I was pretty aware of, just from being a music fan, reading magazines over the years, that if a band is shoved in your face publicity-wise; if they’re on the front cover and have ads everywhere and you can’t escape them, they don’t really feel like [they’re] yours. If you let someone go out and find it in their own time, it probably feels more special to them. It’s like they’ve made the groundwork, and it might feel more like their band rather than everybody’s band.

The self-discovery aspect is always more interesting to indie music fans. Those kinds of artists don’t have a big marketing budget behind them, and it’s generally the fans and critics that propel them forward, instead of the band themselves.

Hopefully it attracts people to your band that actually like your band for the right reasons; they like the music you do and that’s the reason they’re into your band, not for any other reason. It’s more enjoyable, rather than being told to like something.

Reading those interviews, there are lots of mentions of ‘finding yourself in certain situations’, as if you’re indicating that your success is entirely accidental.

It’s not entirely accidental. It’s definitely not the goal. We haven’t done anything to further our career. If we tour overseas, it’s not to ‘crack a market’ or anything like that, or if we put a record out at a certain time, or anything like that. The only thing that is on purpose in this band is the making of the records and playing of shows. I guess everything else is a by-product of that. Maybe accidental is the wrong word. There have been a lot of funny accidents, but we’ve had a ridiculously good run. I guess success has never been our goal. None of us are anti-success; if that happens, that’s awesome, but it’s all a by-product of what we want to do, which is to make the best records that we can.

You’re heavily involved in the Melbourne indie scene with the label and your time at the vinyl pressing plant [Corduroy]. Surely you must have had some idea that the music you were making would appeal to people.

Not really. I don’t work at the plant anymore. I’m not even involved in the label anymore. That’s only a recent development. I guess I’m involved now. When I started, I didn’t really know that many people within that scene. I knew a small group of people from the record plant, but when we had that first jam I really didn’t think that it would appeal to that many people at all. I knew we could probably press 200 7-inches and get away with it, and then our friends and family would probably buy enough of them to make our money back. Beyond that, I thought I’d have them sitting under my bed for a year, then I’ll get rid of them when we play a show, and that will be fine. That’s all we wanted to do, was usually play one show, just to show our friends, “Look what we’ve got.”

I think after the first show I did realise people did really like this. I was sort of surprised and I could see that there were bands before that I felt didn’t really have anything special about them, and when I did play with this band I did feel like there was that special thing that I’ve been looking for in other bands. I noticed that other people noticed that too. There’s no way that I thought that many people would like us. I sort of think if I hear us on triple j or something, I think we stick out really weirdly and don’t sound like a real band or something. I’m actually slightly flummoxed that we’re as popular as we are.

Is it uncomfortable feeling when you hear your songs on the radio?

I don’t listen to the radio that much anymore so I don’t have to bother about it. It’s sort of nice; because I’m so heavily involved with the making of the music and the recording of the music, when I hear it accidentally on the radio or when I’m out somewhere in a shop, I can be a bit objective about it for a second. I can sort of go, “Actually, this is pretty good.” The only way I can hear it as an outsider for a brief second.

Then you think, “Wait a second, I actually recorded and mixed that.”

Yeah, it takes about three seconds before it processes that it’s actually me playing. In those three seconds, I can have this weird brief moment of “Ah, I like this” and sort of feel different about it.

I want to clarify your role within the band. You’re the guitarist, keyboardist, and you mix the albums?

I want to clarify your role within the band. You’re the guitarist, keyboardist, and you mix the albums?

I record and mix them, yeah.

Is the band still self-managed?

Yes, for the first time – for our whole career I’ve just booked the shows and I guess managed the band, just out of accident. We got bigger, and someone needed to do it and I had more time on my hands, so I kept doing it. This coming album tour is the first time I’ve ever handed over any of the responsibility to an outsider; we’ve got a tour manager this time. It’s gotten to the stage where the shows, especially for the album launches, are quite big. I wanted to sit back for once and just enjoy myself and just play. Sometimes, on the bigger shows, I get a bit stressed out with the responsibility of it all, and I’m more waiting for the relief of it to be over, rather than enjoying the show. I thought I just want to go out there and relax for a tour, just let someone do all the other stuff, like booking flights and everything.

Did you find it difficult to hand over the reins?

Yeah. Well, it’s still happening. The tour’s about to start. I think I found it weird. In a way, it’s no less work. You’re still [included] in the same emails, there’s just a middleman now, but I do feel a distance from responsibility, like I don’t feel like, “God, it’s my fault if this tour goes wrong” or something like that. I feel like just a band member and I feel good about it. I think we have gone so far with it being totally insular and doing it all ourselves. I did feel pretty weird to sort finally let go of something. It’s been good so far.

You might be aware that there’s a bit of a backlash about the last album, which tends to happen with almost any band who ‘outgrows their roots’.

I read one or two reviews. I think it was a Tom Hawking review [on The Vine] and then a response to that review that someone alerted me to. To be honest, I think for a band in our position we’ve gotten amazingly far without really having a strong backlash. Even if there is a backlash on the new record, it’s sort of been pretty minute. You put out three records; someone is going to like your first record better than the new one. Plenty of people whose opinion I totally trust think this is our best record. I should just be happy that anyone likes any of our records; I don’t think the backlash is for any other reason despite the music. I don’t care. I don’t like some records. Is that all that the backlash is about? You’re probably more aware of it than I am.

For example, there’s a topic on the Mess+Noise discussion boards called “Eddy Current Backlash” which was mostly about that Tom Hawking review. It currently has 178 responses.

Okay. I’m probably just guilty of Googling my own band and reviews as anyone else. I do realise it’s not the healthiest of habits. [laughs]. I’m not taking it to heart anyway, but I don’t know; that’s fine. It wasn’t a bad review. It seemed pretty genuinely thought-out, smartly written and stuff. It’s just weird for me. People think more about our records than we actually do. That’s the only thing that’s weird to me: I don’t think we’re the type of band you need to dissect that much. “We wrote ten songs in the last year, and we recorded them. Here they are.” That’s sort of how much we think about it. It’s funny to see other people analyse it when there is – it’s like other people care about it more than we do.

I read a quote about your live shows where you said the bigger the band gets, the harder it is to please everyone, and you probably took it to heart a bit at first and you’re trying to make sure everyone is having a good time.

That could equally apply to the records we put out. There was a stage when the shows got a bit bigger and the people that were there at the start weren’t enjoying it as much as the crowds got a bit rowdier. They got pushed to the back and there were jerks there. It would really affect me to find out after the show that so-and-so had a bad time because some dude was being a wanker. Not that I really want to tolerate jerks at any of our shows, but I’ve also got to realise that I can’t control everything and have to do everything I can and then just play a show and enjoy it, rather than stress about every person in the audience. It is a bit harder to control a thousand people compared to fifty.

A Mess+Noise writer asked you in 2006 whether violence at a rock and roll show is ever justifiable. I’d like to put that question to you again, now that you’re quite a bit bigger than you were in 2006.

I don’t think violence at shows is ever justifiable. I don’t think violence anywhere can be justified. I don’t see a place for it, for sure, and I definitely don’t see a place for it at our gigs. I’ve never really understood that kind of reaction to our kind of music. It seems to me sort of fairly good-time music in my head. Maybe I’m wrong.

You mentioned in another interview that Eddy Current can offer support slots to bands that you really like, to help or to expose them to other people. Was this because other bands extended that same courtesy to you when you were starting out?

Yeah definitely, and it’s just more from being a fan of records. For instance, those overseas bands that we’ve played with; I’m sure Thee Oh Sees would have done fine without us, but if we can do a couple of shows and 500 or 1,000 people seeing them that maybe hadn’t heard of them, you know, then that’s awesome. It’s good when overseas bands come out and you’re in a position where you can do that. It’s the same with local bands, friends’ bands, and stuff like that. You just want to play with bands you love and you want to expose. I guess people come to our shows, there are a lot of people now that maybe don’t go to smaller gigs and stuff like that. If we can just expose some good bands, then you feel like you’ve done a good deed.

You’re paying forward what you felt in the past couple of years, when you were growing your fanbase.

Totally, and also like all the bands I grew up watching when I was first turned 18, 19 – bands like The Exotics and The Breadmakers – to be able to now put them on shows in front of younger dudes who wouldn’t have seen them before. It’s repaying that favor to those bands that have entertained us a heap over the years.

I want to ask you about the live music scene in Melbourne at the moment, because I saw that Eddy Current were involved with The Tote’s final show. Did you attend the SLAM rally?

I want to ask you about the live music scene in Melbourne at the moment, because I saw that Eddy Current were involved with The Tote’s final show. Did you attend the SLAM rally?

I didn’t, actually. I’m glad it went really well. I had a mixing session to help a dude finish a record that day. I thought of cancelling, but then I thought “what’s the point?”. I thought it would be more proactive to sit there and help someone finish making music than actually go protest about not being able to make music.

I’m not trying to guilt trip you for not being there, you know.

Not at all, I was just explaining. [laughs]

Following The Tote’s closure, how do you feel about the live music scene in Melbourne? Do you think it’s healthier, or really struggling because of those liquor licensing laws?

I always say the wrong answer to these kinds of questions. I don’t think I said the things that people wanted to hear when The Tote closed. But The Tote was great, The Tote was awesome to my band and it was a good place for years. In that time, I know a lot of venues have closed down, but a lot of venues are still open. It seems to me – I guess I’ve been in the city for 11 years or so – like Melbourne has more venues [now] than it did 10 years ago. There seems to be more bands.

Shit’s gotta die off and get fresh again. I think good things will happen, and good things will continue to happen, and even though it seems sad now, it’s probably good in a way. Things might get stale and younger dudes will start new venues and we’ll all think of different ways of doing things. I think Melbourne is strong enough to survive with one less venue.

To change topics entirely, I want to ask about the masks on the cover of Rush To Relax, even though probably every other music journalist you’ve spoken to has asked the same question.

No-one has actually asked about the masks.

What inspired you to use them?

I don’t know. Nothing, really. I think we just had the idea for the film clip before we had the cover. We wanted the film clip to look a bit creepy. We just wanted a creepy-looking film clip and then we had the idea of shooting the cover on the same day because we didn’t want to hire a plane twice. Maybe we were just scared of our own faces on the covers, but there is no symbolic meaning behind the masks. They were cool, so we put them on.

It’s the first release of yours where the band actually appear on the cover.

I know, I think people were getting a bit sick of our other covers. [laughs]

So the masks weren’t a matter of trying to protect your anonymity?

Not really. We’re pretty conscious of never wanting to be the ‘four dudes in leather jackets down an alleyway’ type of band. It happened because of the film clip. We had an idea for the film clip and we didn’t really want to – we wanted a different look for the film clip. That shot [the album cover] just happened to be a shot from the day of the film clip. That’s all there is to the masks.

Not really. We’re pretty conscious of never wanting to be the ‘four dudes in leather jackets down an alleyway’ type of band. It happened because of the film clip. We had an idea for the film clip and we didn’t really want to – we wanted a different look for the film clip. That shot [the album cover] just happened to be a shot from the day of the film clip. That’s all there is to the masks.

How much attention to you guys pay to the band’s image?

Not much. There’s not really much difference between the way we look or act on stage or in the band than how we do in normal life. I guess the only attention we’re paying is just giving accurate representation of ourselves. That’s about it.

You actually hired a plane for the album shot and the video clip?

Yes.

Which company did you go with? Did they dig the concept of what you were doing?

It was pretty hard to find a company that still does those old plane banners. I think it was a guy called Sky Surfers down in some town in country Victoria. I always used to like those banners as a kid and I always wanted one. Our album cost nothin’, and our friends film our videos, and I guess we won some money last year [the AMP] and I felt like we should show that we spent it on something. So we might as well get a stupid big plane. When it came flying over, while were waiting to film the clip, it was seriously the most exciting event. We were just jumping up and down going “yes!”

“We’ve made it. We have a banner!”

Totally, man! It was like “box ticked – I can retire now”.

Do you still have the banner?

Unfortunately, they just recycle the letters and you can’t keep the banner.

Drag.

It would have been excellent to put it up at the back of our gigs or something.

It would. With each album you’ve kind of gone backwards. I read that Rush To Relax was recorded even cheaper and more quickly than the last one. Do you see a logical conclusion to this pattern? Will you end up recording an hour-long album in an hour?

I always thought about it but I think probably not. I can’t see how we can do it much more quickly and cheaper than this one. Definitely not any cheaper. Too much attention is paid to how long it takes for us to record albums. It’s not like we’re trying to prove a point. I have the recording gear so it doesn’t cost us anything. We’re comfortable with doing it that way, and that it sounds okay for what we’re trying to do. Unlike some bands maybe, who go into a recording session to write songs or something, we have 12 – 15 songs written and ready to go. It’s basically just setting up.

I always thought about it but I think probably not. I can’t see how we can do it much more quickly and cheaper than this one. Definitely not any cheaper. Too much attention is paid to how long it takes for us to record albums. It’s not like we’re trying to prove a point. I have the recording gear so it doesn’t cost us anything. We’re comfortable with doing it that way, and that it sounds okay for what we’re trying to do. Unlike some bands maybe, who go into a recording session to write songs or something, we have 12 – 15 songs written and ready to go. It’s basically just setting up.

The album is only 40 minutes of music, so I always thought if you can’t play the songs you’re trying to record well after three takes, you shouldn’t be recording it. We try a song a couple of times and hopefully it’s done. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Brendan always seems to be quirky and out of time, and there’s plenty of room for bum notes and stuff like that. I like that kind of thing about this kind of music. We’re not trying to achieve any kind of perfection. Six hours [to record an album] is plenty of time.

On the other end of the spectrum, do you ever see yourselves being victims or locking yourselves in the studio for a week to really nail it out properly, with a big name producer and all that sort of music industry bullshit?

I’m not against that kind of thing. I don’t think it suits our band. I just don’t think it would work. I’m pretty sure that this way is the correct way for this band. It’s not necessarily how I’d do it for any other band or any other band I’d record. I don’t think it’s definitely the way to do it, I just think that it works for this band.

Having said that, I don’t walk out at the end of the day with a finished product. I still bring it home and mix it, and spend some time making it sound okay. There is other time beyond those 6 hours, but I just guess we have the luxury of having our own gear and I relatively know what I’m doing. I can just mix the record in my bedroom. It’s nice to be in the position where you don’t have to rely on producers and studios.

Are you happy to keep doing that for the next few Eddy Current releases?

Yeah, I think so. For a new song we just wrote, I’ve got a very different idea that I wouldn’t mind trying a different way. I think I’m happy with, if anything, I can see us doing it sort of rougher. Like, I think we can experiment with some 4-track cassette recordings rather than 8-track, and I think I’d really like the drum sound we’re getting on that, so if we do some more stuff I wouldn’t be surprised if we regress even further.

That sounds like the ultimate way to make money: to be completely DIY indie, to release the album for nothing, and just to tour on the back of it and make money.

I guess it’s a way of keeping costs down, that’s for sure.

Eddy Current are credited with having a large impact on the Australian punk and garage revival scene. What are your thoughts on that?

I think there have actually been a couple of bands that have sprung up since that I feel some sort of kinship with, but I think if it wasn’t us that did that, it would have been someone else. I think it was one of those things that were going to happen anyway. We just happened to get in first.

I read that you’re fond of playing house parties and small gigs to ‘keep it real’ for the old fans.

I think it’s mainly for our sanity. If we play the big shows in Perth all the time, we just go nuts. I guess just to do an occasional really small show and house party is just really to keep us sane and to remember that type of show and enjoy the show. I guess it keeps things as diverse as possible.

The upcoming tour you’re playing mid-sized kind of venues. In Brisbane, you’re playing The Zoo.

Which is pretty big for us. I think we’ve only played The Step Inn in Brisbane, so I guess The Zoo seems like the logical step up, up there. Brisbane hasn’t got a lot of options.

No, it really doesn’t. Between The Zoo, which is 450, I think the next step up is the Hi-Fi, which is 1,000+.

I don’t think we’re ready to go to that, not in Brisbane anyway. I don’t think our following is that strong up there.

I read a quote where you said you’ve done a good job with distancing yourself from the music biz. I saw that you turned down SXSW, which a lot of other Australian bands probably wouldn’t do. They’d probably view that as a massive opportunity.

It was probably bad timing, but I’d just rather go over there and play a lot of shows and not really worry about that kind of stuff. I think SXSW is probably really enjoyable for a local because you get to see a lot of bands, but unless you’re going there for a reason and trying to become something, it’s probably not the best time to play a show. I’d rather wait until things die down and do a normal tour.

Considering there are 1,500 or 1,800 bands playing in a week or something.

Totally. It almost sounds like it’s working against its purpose.

I’ve read that you’ve got quite a broad taste in music, Mikey. I want to know what inspired you to play guitar in that Eddy Current style.

I don’t know; I’m sure it’s a bunch of things. Definitely my time at Corduroy [Records, a vinyl pressing plant], being surrounded by those type of bands and musicians and stuff, had an influence on the type of music I play and how I play. I spent three years listening to teenage garage records from the ‘60s or something, and I realised that that’s the sound of guitar I like and I’m going to try my best to rip it off.

I have one last question. It’s about the Australian Music Prize. It’s gone from Eddy Current’s indie garage sound to the current winner, which is a major label-distributed album by a former Australian Idol contestant.

This is a loaded question, isn’t it? [laughs]

I just want to gauge your take on that.

That’s fine. I think it’s definitely reactionary. I think it was pretty obvious the day after we won it that they were going to give it to a chick this year. I haven’t heard Lisa Mitchell’s records so I’m not in a position to say if it’s a good record or bad record. I think I heard one of the songs on the radio and quite liked it. I guess if they’re doing it for why I say they’re doing it, it shouldn’t really matter if it’s on a major or indie or if it’s an Australian Idol winner or not. If they honestly think it’s the best record then so be it.

That’s a very diplomatic response.

I’m so out of the loop that I probably haven’t heard any of the records on the damn thing anyway. I don’t think I’m really the best person qualified. I have no ill feeling towards that.

That’s all I’ve got for you, Mikey.

Hopefully there’s something there. I rambled.

++

Check out Eddy Current Suppression Ring on MySpace, and view the video for ‘Rush To Relax’ below.

Last week I wrote a

Last week I wrote a

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world.

We have to pay attention to how our records and our videos and everything is distributed because we make ‘em and we care about how they get out there, but I wouldn’t be a student of the music industry’s technicalities if I wasn’t convinced that the animating passion in my life is making things, and how the distribution of them affects that. I know it sounds incredibly circular, but I don’t particularly care if the music industry works until I make something and it fucks up the way I want that thing to be shared with the world. Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think.

Yes, in essence they do. I think that the value in music from which we derive the money in music can no longer be generated by limiting access. The way you assess value in most commodities is related to supply, the whole supply and demand curve. The reason you have to pay to have most things is because someone else restricts your access to them or you have to pay for the access to them. There are certain things that don’t follow that model and music has sort of jumped the barrier, I think. First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it.

First of all, I’ve been talking this whole time as if I have a kind of answer, like I know exactly what’s going on and there is an obvious path forward. I don’t know what the ramifications will be. The first step that seems obvious to me is we do need something like record labels to perform some of the functions record labels traditionally have. This is what I think the critics of major labels often miss, is that for all of their exploitative, greedy, and short-sighted policies, they did provide a risk aggregation for the world of music making. They invest in however many young bands a year and most of them fail. Those bands go back to their jobs at the local coffee houses without having to be in tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of personal debt for having gone for it. Andrew Wilson of Die! Die! Die!

Andrew Wilson of Die! Die! Die!

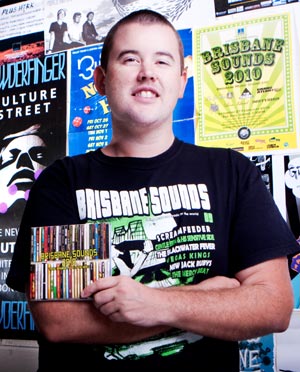

I first met Blair Hughes when he began working the door at The Zoo, one of my favourite live music venues, sometime in 2008. We’ve since struck up a friendship around

I first met Blair Hughes when he began working the door at The Zoo, one of my favourite live music venues, sometime in 2008. We’ve since struck up a friendship around  Sixfthick,

Sixfthick,  Have you approached triple j with the compilation? What kind of response have you seen from them?

Have you approached triple j with the compilation? What kind of response have you seen from them? Who do you plan to meet while at these conferences, and why? What’s your networking plan of attack?

Who do you plan to meet while at these conferences, and why? What’s your networking plan of attack?

In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks.

In late 2009, my girlfriend and I went to England for three weeks.  I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].

I see. As I mentioned earlier, I also went to the Mount Buller event [the first Australian ATP event, curated by Nick Cave (pictured left) & The Bad Seeds].  I saw in an

I saw in an  That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.”

That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer to that. To be honest with you; I really loved the Mt. Buller event [pictured left]. It was really special, really great. The lineup that was up there and that setting, especially that second stage where you could see all the mountains behind it, through the stage. That was amazing, but it was just the spirit of people that were up there because I think a lot of people have gone to things like Big Day Out and Homebake and that. Those things are good for what they’re designed for. They seem like a breath of fresh air for a lot of people. That’s how ATP was when it started in England 10 years ago. People were like, “Fuck, great, we can go see 20 bands all at one weekend instead of having to wait all day for someone to come on at Reading, or something like that.” Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that?

Do you thank [Dirty Three frontman, pictured right] Warren Ellis often for that? I know you’re a big fan of

I know you’re a big fan of  I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator]

I’m in the process, I’m still booking Pavement, which is next year, and [The Simpsons creator]  There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good.

There are times when it goes out, but this weekend has definitely been a great one for us, just so many bands – they’re all old curators and people who have recorded for us, but also friends. Every time you walk around it’s like, “Hey, how are you doing?” The spirit here has been really good. Steve [pictured right]: The reason I got into the music industry is because I’ve always loved music. From my early twenties, what I wanted was to get into the business side of it. Then I kind of got into the whole creative thing. I went to work at an indie label after graduating from uni, called

Steve [pictured right]: The reason I got into the music industry is because I’ve always loved music. From my early twenties, what I wanted was to get into the business side of it. Then I kind of got into the whole creative thing. I went to work at an indie label after graduating from uni, called  From there I got offered a job at a record label,

From there I got offered a job at a record label,  Steve: Kind of seems really obvious but I guess it wasn’t like a eureka moment but it was like – Kasabian is sort of synonymous with football, especially here in the UK.

Steve: Kind of seems really obvious but I guess it wasn’t like a eureka moment but it was like – Kasabian is sort of synonymous with football, especially here in the UK. Phil: That was okay. We knew that was going to be alright so it really came down to would the footballers have enough time to practice, because it was something that wasn’t going to be easy to play.

Phil: That was okay. We knew that was going to be alright so it really came down to would the footballers have enough time to practice, because it was something that wasn’t going to be easy to play. Steve: Most people we’ve spoke to since are like, “Where is it?” [laughs] We had to take it down, which was a shame.

Steve: Most people we’ve spoke to since are like, “Where is it?” [laughs] We had to take it down, which was a shame. Phil: You’ve got to get out there and put yourself into their head essentially, and think, “Alright, if I was this type of person, what would I…” The actual people in the insight department will go as far to do this. They’ll spend a week in the life of a particular segment; they’ll consume the right media, go to the right things, so they’ll try to experience that person’s world so they understand it better.

Phil: You’ve got to get out there and put yourself into their head essentially, and think, “Alright, if I was this type of person, what would I…” The actual people in the insight department will go as far to do this. They’ll spend a week in the life of a particular segment; they’ll consume the right media, go to the right things, so they’ll try to experience that person’s world so they understand it better. That’s what I really enjoy, just getting my teeth into something that looks impossible and trying to make it happen. We’ll be trolling through the Internet, looking at writing programs, and drawing things, and trying to work out if we can make something work. It’s another fun side of it, what’s coming next, what are we going to do next.

That’s what I really enjoy, just getting my teeth into something that looks impossible and trying to make it happen. We’ll be trolling through the Internet, looking at writing programs, and drawing things, and trying to work out if we can make something work. It’s another fun side of it, what’s coming next, what are we going to do next. I

I