GQ Australia story: ‘Shock To The System: Electroconvulsive therapy’, March 2012

My first story for GQ Australia magazine: a 4,200 word feature about the psychiatric treatment electroconvulsive therapy, otherwise known as ECT or ‘electroshock’. This story appeared in the Feb-March 2012 issue of GQ.

Click the below image to read the story in PDF form (link will open in a new window), or scroll down to read the article text underneath.

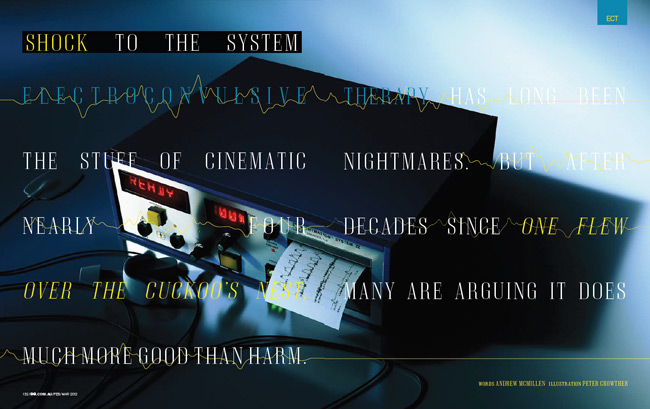

Shock To The System

Electroconvulsive therapy has long been the stuff of cinematic nightmares. But after nearly four decades since One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, many are arguing it does much more good than harm.

Words: Andrew McMillen

As the young man is led into the operating theatre, the smell of salt water and sterilisation fluid hangs in the air. The room is unremarkable; all greys, blues and whites, just like any other theatre in hospitals across the country, except for a couple of innocuous-looking machines stacked on a bench. Twenty-five-year-old John Vincent doesn’t know it yet, but those machines would soon change his life.

Helped onto a gurney, Vincent lies flat on his back as a clamp is placed on his index finger to monitor his oxygen levels. He feels the cold wipe of saline solution on his collarbone, biceps and forehead, before a nurse applies several electroencephalography (EEG) electrodes to trace his brainwave activities. Moments later, a general anaesthetic makes its way up his arm, and he drifts out of consciousness.

Having been sedated, he doesn’t remember what happened next, but it goes like this. A specialist affixes an electrode to the middle of his forehead, and another one above his left temple, then switches on the Thymatrons – those machines in the corner – sending a series of short electric shocks coursing through his brain, bringing on a grand mal seizure. Fifteen seconds later, it’s all over. The current is switched off, the electrodes removed, and Vincent is wheeled into an adjacent recovery room.

It might sound like a scene from a ’70s movie, from the days of roguishly experimental medical procedures, but this was Boxing Day 2010, and Vincent had just received his first course of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) at Toowong Private Hospital in Brisbane. A psychiatric treatment most commonly used on those with severe depression, ECT – better known by its outdated term, electroshock – is also called upon to treat patients suffering from acute mania or, in Vincent’s case, bipolar disorder. And despite the popular public perception of ECT as a barbaric, archaic practice, the treatment is administered on a daily basis at both public and private hospitals all over Australia.

Growing up, Vincent was a happy kid. He had lots of friends, enjoyed playing soccer, and loved going fishing with his younger brother while on regular camping holidays with the family. Then, aged 17, in his final year of high school, Vincent was diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

As he got older, his mental illness became harder to manage. “John was existing, but he wasn’t happy,” recalls his mother, Tina, a kind woman in her early fifties with a fair complexion and green eyes who runs a small business alongside her husband. “He wasn’t right, and at some stage he decided to go off his medication. Unfortunately, with his type of bipolar – type one – when he goes off medication, he goes into a state of catatonia. Everything shuts down; no communication, nothing happens.”

Things worsened as the years passed, and by late 2010, Vincent was living a life of isolation in Townsville, north Queensland. He’d withdrawn from the people around him: friends, family, even the younger brother he lived with. “You know those wildlife documentaries on TV, where they record the animals’ every move, behaviours and moods, and all that?” he asks, his hazel eyes burning with intensity. “I felt like I was an animal; like I was being surveyed.”

This was a dark time for Vincent, who says he spent a lot of time in his room “trying to hide away”. He constantly felt as though there was someone outside looking through the windows at him, recording his behaviour.

One Friday in December, his parents went to Mackay for their first trip away together in a year. The next morning, Tina and her husband received a call from their youngest son. “He didn’t think John was all that well,” she says. “We jumped on the first plane and came home. We spent all Saturday with John. He continued to decline into a catatonic state; not eating, not talking. It was almost like he was in a coma.”

By 5pm, Vincent’s movements had become “robot-like”, with his body barely responding to the signals sent by his brain, and the famil rushed him to the emergency ward at Townsville General Hospital, before he was transferred to the mental health hospital. “It’s pretty sad, because there just aren’t enough facilities,” says Tina, remembering how they how desperate they were for a solution to their son’s illness. “We turned to friends in the medical profession, who gave us a great deal of support and help.”

A man named Dr Josh Geffen was mentioned, who specialised in ECT at Toowong Private Hospital. Vincent had never heard of ECT before his parents brought it up, but since he was in such a low mental state at the time, he didn’t argue. “I just went with it,” he shrugs. “I cooperated, and followed my parents’ advice. I did what I was told.”

He hardly remembers a thing about the journey. His mother continues: “We got John down to Brisbane straightaway, and when Dr Geffen saw the state John was in, the first thing he recommended was ECT,” she says. “We were pretty horrified; we’d heard stories from the olden days of ‘shock treatment’ and that sort of stuff. We hadn’t really given ECT a lot of thought. It’s a little bit frightening, because you really don’t know what’s involved. But Dr Geffen explained everything to us, showed us a DVD, and put our minds at ease. We consented to John having the ECT, and he agreed to it, too.”

They got to work immediately. Doctors warned Vincent that the muscles in his arms, legs and shoulders might feel sore once he came to, after receiving the electric shocks. And indeed, he did feel uncomfortable for a couple of hours – he likens the muscle soreness to the day after a big gym workout – but says, “Afterwards, I felt fine. It took a while for the anaesthetic to wear off, but after that I was OK.”

Vincent’s story is more common than you might think. Statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show that in the 2009-2010 financial year, 26,848 individual ECT sessions were administered throughout Australia – although the exact number of people treated is unclear, as patients tend to have multiple sessions. “A typical course of ECT involves between six and 12 treatments,” explains Dr Aaron Groves, the director of mental health in Queensland, adding that, while ECT can be used on people of all ages, since depression is more common in adults than in children, around 80 per cent of treatments are on patients aged 30 to 80.

Based on those figures, on any given day here in Australia, 73 people get hooked up to a machine and jolted with electricity in the name of medicine. What’s more, far from being a curiosity from the past that hasn’t quite died out, it’s actually on the rise. Why? Well, because it works.

++

Electroconvulsive therapy has its roots in early schizophrenia research. In 1934, Hungarian neuropsychiatrist Ladislas Meduna saw improvements in schizophrenic patients after seizures were induced with chemicals such as camphor and Metrazol. Three years later, Italian neuropsychiatrists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini discovered that these seizures could be more easily induced by electricity. In a TED.com presentation uploaded in October 2007, an American surgeon and author named Dr Sherwin Nuland relayed an eyewitness account of the first time ECT was performed on a human in 1937.

“They thought, ‘Well, we’ll try 55 volts, two-tenths of a second. That’s not going to do anything terrible to him.’ So they did that… This fellow – remember, he wasn’t even put to sleep – after this major grand mal convulsion, sat right up, looked at these three fellows and said, ‘What the fuck are you assholes trying to do?’ Well, they were happy as could be, because he hadn’t said a rational word in the weeks of observation. They plugged him in again, and this time they used 110 volts for half a second, and to their amazement, after it was over, he began speaking like he was perfectly well.”

“It eventually became apparent that it was a much better treatment for depression than schizophrenia,” says Dr Jacinta Powell, clinical director of mental health at the Prince Charles Hospital in Brisbane. “This is how these things develop: psychiatrists make leaps of logic, they try them out, and see whether it works.”

What they hope for with any treatment is remission. So, how does ECT stack up against other methods of treating depression?

According to statistics presented in May 2011 at the American Psychiatric Association Conference in Hawaii, 34 per cent of ECT patients were in remission after two weeks of treatment. Four weeks later, that had risen to 65 per cent; and after a full course of ECT, that figure reached a 75 per cent remission rate. Those success rates aren’t just good; they’re remarkable.

So, why are we still so scared? Perhaps Dr Geffen [pictured right] – the man who treated John Vincent – would have some answers. A stocky, silver-haired man in a dark suit, he leads me into the theatre where John was first treated on Boxing Day. He drags in a couple of chairs from the waiting room, which is adorned with intricate paintings of wildflowers and a poster entitled ‘Understanding Depression’. We sit in the middle of the theatre and begin talking ECT. “Intuitively, it does seem like a worrying thing to do,” he admits, “to pass a dose of electricity through somebody’s brain in order to treat them.”

And he’s right. A seizure-inducing electrical current sent through the brain, where all our memories, emotions, likes, dislikes, fears and secrets are stored; where our very personality is kept? The mind recoils in horror at the thought alone.

That’s partly because, for the majority of us, who haven’t had any first-hand experience of ECT, our knowledge is mostly based on what we’ve seen in movies. Take One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest – the 1975 Miloš Forman adaption of Ken Kesey’s 1962 novel.

You’ll remember the scene when the main character, Patrick McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, is judged to be so disruptive to the daily routine of his fellow psychiatric ward patients that doctors see no alternative but to treat him with ECT.

McMurphy is led to a bed, his hairline coated with a conductive gel and a piece of leather placed between his teeth. Electrodes are applied to each temple, and his brain is exposed to a current of electricity. There’s no anaesthetic, nor is the patient forewarned of what’s about to happen. McMurphy appears to be in severe pain, with several men restraining his wildly convulsing body. It’s unclear whether McMurphy’s treatment is an attempt to ‘fix’ him psychologically, or simply to punish him for being a trouble-maker, but it was a very convincing performance that won Nicholson an Oscar, a Golden Globe, and a BAFTA for Best Actor.

“It’s a great movie. I love Jack Nicholson; he’s fantastic,” says Dr Geffen, with a grin. “It’s also nothing like modern ECT. It was set during a time when anaesthesia was already involved, so a bit of creative licence has cost us quite a lot of bad press.” He continues with his list of ways the film misrepresents modern ECT. “No treatment electrodes are placed on people until they’re asleep, because it’s not a very pleasant feeling if you’re coming in for your first treatment,” he says. “It’s much kinder for the person who’s anxious about what’s going on.”

It’s also worth noting that the vast majority of treatments do not induce enormous, full-body convulsions like the reaction portrayed by Nicholson. In most cases, the only physical sign of the electrical current is a slight twitching of the patients’ fingers and toes.

At the Prince Charles Hospital, Dr Powell shows me a segment from the 1990s-era television program Good Medicine, in which a greying man in his mid-forties is treated with ECT. The footage of his treatment is so incredibly mundane and unremarkable that I can’t help wondering what all the fuss and controversy is about. Particularly given the guidelines adopted by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists in 1982, which note that it’s “among the least risky of medical procedures carried out under general anaesthesia, and substantially less risky than childbirth.”

“It’s a very effective treatment for very ill people,” agrees Geffen. “It’s more likely to get you into remission than any other treatment.” Success rates with medication when used as a first-line therapy are only 30 per cent, he says. After a year of trying different strategies, this may rise to around 60 per cent in a best-case scenario.

And what about therapy for depression – you know, the kind where you lay on a couch and talk things through?

“The type of depression we see here, people are too sick to be having much talking therapy. Not that talking’s unimportant, but that’s part of the post-recovery.”

Yet somehow, even though lying on the therapist’s couch isn’t the right thing, and months of antidepressants aren’t very effective, people are instinctively more keen to stick to those methods than to volunteer to be subjected to a series of electric shocks.

“A few things soften that,” says Geffen, ever the salesman. “The dose of electricity is quite small; 0.8 to 1 amp. I was treating an electrician, and I asked him, ‘How can I explain it to people?’ He said, ‘Well, it’s about 10 per cent of what a toaster puts out.’ Now I always tell people, ‘Don’t stick forks in toasters, please!'”

Geffen breaks into a wide smile and continues, “Another way to put it is that the current is enough to light up a 25 watt bulb for about one second. Once or twice in the process, I’ll pass the electricity across my hand, and feel a little jolt. But it doesn’t throw me to the ground.”

And of course, ECT isn’t the only instance of doctors using electricity to reset an organ that’s not operating properly; cardioversion, for example, applies the same theory to correct a malunctioning heart. “I do wonder, sometimes, why the person who cardioversed Tony Blair is the ‘cardiologist hero’,” Geffen says, “but I can be painted as a ghoul for trying to treat people’s depression.”

++

Part of our reluctance to embrace ECT, though, may well be because, despite years of research, it’s still a bit of a mystery. We know it works best when used to treat severe depression, but when it comes down to it, we don’t really know why. “At one level, that’s true,” agrees Geffen. “We don’t fully understand all of the mechanisms of its action. However, that’s true of many treatments in medicine. We do know how damaging severe depression is to people’s brains and their lives. At another level, we’re understanding a lot more about how it works, as well as the key chemicals involved in depression: serotonin, adrenaline, dopamine, and this – being a powerful treatment – influences all of them. Most antidepressants work on one, or – at most – two of those. ECT is a potent stimulus for brain cell growth.”

His sentiments are echoed by Dr Daniel Varghese, a Brisbane-based psychiatrist in both the private and public health fields. “I think it’s true to say we don’t really know why or how it works,” Dr Varghese says.

“But then again, we don’t know why or how people get severe mental illness either, because the brain is clearly an inherently complex thing. That’s something that psychiatrists and people with mental illness have to deal with in a range of illnesses: we don’t really know why, but we do know some strategies and treatments that we’ve found to be helpful.”

++

Of course, it’s important to make it clear that ECT is not a catch-all miracle cure for depression, and some of the fears surrounding its usage are real. It certainly has its fair share of detractors.

On a chilly morning in the Brisbane suburb of Highgate Hill, I meet with Brenda McLaren, a spritely woman who loves to talk. Her face is riddled with deep wrinkles, which make her appear far older than her 57 years. Her memory is shot, however, and she has prepared notes in an A5 notebook ahead of my visit. Her relationship with ECT has not been an altogether pleasant one. She was first treated in 1988, as a severely depressed 34-year-old. At first she consented, as she wanted to get better and believed that the doctors at Prince Charles Hospital were acting in her best interests. Over 20 years later, she’s not so sure.

Brenda smokes a cigarette on the sun-soaked front balcony of the Brook Red Community Centre where she works as a peer support worker, and reads her handwritten notes. In 1988, her youngest son was six. “I can’t remember him between the ages of six to 15,” she says. “In some ways, [ECT] must cause some sort of brain injury for that to occur. He talks to me about things, and I honestly don’t remember.”

“My other children would come up to visit me at that time,” she says, “and I wouldn’t know who they were. This would happen quite regularly after ECT. This made them hate the whole system, which is still a big thing with them. It created relationship problems within the family. I’m not saying there weren’t already problems, but it didn’t help. Because… how can a mother forget her children?”

She looks up with sadness in her eyes, and it’s clear the memory loss still hits her hard. “It made me feel very guilty. When you really think about it, in some ways you lose your identity,” she says. “You lose who you are.”

“I would be the most forgetful person here,” she says of her peers at the Centre, which supports people living with mental illness. “I put things down constantly, and never know where they are. I lose things. I believe it’s affected that part of the brain that makes you remember things, long-term. I find it hard to retain information. I find it hard to bring information out. That’s why I’m reading this.” She points at her notebook.

McLaren says she received “dozens” of courses of ECT in her life, the last of which took place around 13 years ago. “I know they do it as humanely as possible,” she says, “but I think it’s barbaric, and in some ways, it’s a form of torture. If I was told I needed ECT today, they would have to take me screaming. Because I will never sign to have ECT again. Ever.”

++

In an adjoining room to the ECT theatre at Toowong Private Hospital, Dr Geffen and his colleagues have written some literary quotes on a whiteboard to keep them focused on the job at hand. “Diseases desperate grown by desperate appliance are relieved, or not at all” – William Shakespeare. “Diseases of the mind impair the bodily powers” – Ovid. “When you treat a disease, first treat the mind” – Chen Jen.

I tell Brenda McLaren’s story to Geffen, interested to hear his thoughts. “I feel sorry for her,” he says, after listening carefully. “I believe her when she says that ECT has damaged her memory, and that this affects her sense of identity. Recurrent ECT of this nature is a difficult scenario; if she was severely suicidal or malnourished from depression it may have saved her life, although obviously at some cost.”

What Brenda described is, he says, a mixture of the common side effect of peri-treatment amnesia – loss of memory of the period around treatment – as well as the rarer retrograde amnesia, which is the loss of memory for “weeks, months, even years” before being treated. “With modern techniques, the peri-treatment amnesia is less severe and retrograde amnesia is even rarer,” he says.

That’s partly thanks to the more recent side-lining of a variation of the treatment, called bitemporal ECT, in which an electrode is placed above each temple (as seen in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest). ECT guidelines note that “bitemporal ECT is associated with greater cognitive impairment, but these effects vary from patient to patient. Any memory impairment is usually resolved by 4-6 weeks following ECT, but a number of patients report persistent difficulty with retrograde memory.” The other, now more popular, method is unilateral ECT, where one electrode goes above the temple on the non-dominant side of the brain, while the other sits in the middle of the forehead.

We return to Brenda McLaren’s experiences. “The issue of difficulty learning new information some 13 years later is more problematic,” says Dr Geffen. “It’s not generally described in the literature, and may be contributed to by age, depression, and the impact of lifestyle factors like smoking. But,” he admits, “it is hard to rule out ECT as a factor.”

Geffen has been immersed in this world of ECT for more than 15 years. “We start at 6.30am every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, and we’re done by 9am; 10am if we’ve got a long list,” he says. “It’s generally done in the morning; it’s a lot kinder to do it then, as our patients fast from midnight.”

As he said earlier, it’s a treatment for the very ill, and here in this room, Geffen only sees those closest to the brink. I wonder whether the constant exposure to the severely depressed takes a mental toll on him. “When you see patients who are distressed coming in, or patients who have a really good response, you take that home with you and think about it a little bit,” he says, and then smiles. “My wife works in mental health, so it allows for a bit of pillow talk. She’s very familiar with all of this.”

What does he say when asked what he does for a living? “I talk quite openly and freely to my children about what my job is, and explain to them about this,” he says, gesturing at his workspace, with a hint of pride. “Although it’s a stigmatised area, there’s nothing terrible that we do here. We help people who haven’t done anything wrong; they have a brain illness. In that sense, in my social life, I do carry on that view that you can de-stigmatise this.”

++

John Vincent isn’t sure whether he received eight or nine treatments of ECT in total, as he, too, experienced peri-treatment amnesia. “I can’t remember a lot of things that happened when we were back at school,” he says with a shrug. “Birthdays, big events, I can’t remember so much. Things close to me I still remember, though.” Childhood camping and fishing trips, for example, take a while to recall, but his foggy mind does eventually reach back to find the details.

It can be difficult, but he’s philosophical. “I’d rather feel happy, and more myself, than have memories,” he says with a tone of finality. “My health is worth more than having memories.”

Vincent says his course of ECT made him feel more lively. “I’m not so anxious anymore. I’m not short-fused or jumpy. Now I feel more cooperative; I get along a lot more with people.” Not that ECT was a quick fix. “It was a gradual recovery. It wasn’t as though, when I got out, I was right as rain again. It took a while to slowly get to that stage where I felt comfortable.”

His parents stayed at John’s bedside for 12 hours a day through his month-long stay at Toowong Private Hospital. His mother remembers that, within 24 hours of John receiving his first treatment of ECT, she and her husband could see a “definite improvement”.

“John’s had very good results with it. It’s been really quite incredible,” she says. “It’s almost like having a flat battery in a car. You put the jumper leads on and give it a bit of a boost, and it comes back again.”

She doesn’t really understand how it works, and she doesn’t care: she’s just glad to have her eldest son back again. It’s been two months since his last treatment. “He’s on track, and everything is going well. Geffen says, ‘If you go for three months and you don’t need any more ECT, and the drugs are keeping you level, everything’s good,'” Tina says.

“We had no knowledge about ECT until John went into this meltdown and went into hospital,” she continues. “I think the more people talk about it, the better it’ll be. The more I can tell people, and the more open you are about it, the more it will become accepted.”

As for Vincent, now that things are on the up, he’s looking forward to returning to work at his parents’ small business in Townsville. He’d like to settle down with a girl and he can see himself – one day – getting married and having kids, “but they’re a while away yet,” he says with a grin. Vincent isn’t sure what career path he’ll take – something to do with machinery, perhaps, as he’s always had an interest in that area – but he knows that, thanks to ECT, he’s in a better mental state to confront the future than ever before.

*Names have been changed.

Note: due to an error in the production process, a photograph of Dr Josh Geffen’s father, Laurence, appeared in the original article, rather than Josh himself. This error has been corrected in this blog entry.

For more on electroconvulsive therapy, visit Wikipedia. If you are feeling depressed or suicidal, please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, which is available 24 hours a day.

Really good article, great work.

wow! nice to be on the same page and have an awareness of other consumers lived experiences with ECT.

I coordinator the ECT suite at the Prince Charles Hospital, a mental health nurse of 13yrs. I love it! I love the mind and it’s mysteries. The {untouchable} sense we dont always know everything about its greatness. I love life, people of all walks & talks.

My role is but a piece of the puzzle which completes and contributes to a consumers landscape, spiritual peace, kindness and compassion.

I am inspired by the above stories to continue to provide, support, educate and research to keep every current and future consumer who may enter our welcoming doors to Electroconvulsive Therapy!!!

I believe you are the heart function of your mind you can create your reality or live in a delusion lost and scared. Live, love and be happy.

Thought you might be interested in a controversy – extend yourself to include ALL the info. On reading your web page about ECT I find it interesting that you have accepted the all the data provided by the ANZCP, `absolutely safe and effective, the best thing for depression since sliced bread, NO `permanent’ damage to the brain.’ This sunshine and light view of ECT is not supported by the evidence.

Psychiatrists are well aware that there IS damage to the brain, and it is highly likely to be permanent. (Sackheim 2007). They admit it to each other. (Recorded at a convention in California in 2007, well over half agreed.)

Let’s look at memory/cognitive damage. Doctors comments: “During the course of the treatment, many people experience problems with short-term memory, but this side effect only lasts a few days or weeks. A few people, (one suggestion 1:200, but this is actually the ECT death rate for over 65‘s in the US), however, experience long-term difficulties with memory. This effect is more common in people who undergo bilateral, rather than unilateral, ECT.”

In fact, serious and permanent retrograde autobiographical memory loss occurs in over 60% of people who have received ECT. This is not a few. Anterograde, or working memory, for recent and current events, is also affected and results can also be permanent.

Neuropsychological reports indicate that people can lose 30 points on their IQ scores, accompanied by specific losses in cognitive function in the right brain and the cerebral cortex. Physical coordination, (dancers, sportsmen,) creativity, (artists and writers,) the organisational skills and the `higher’ human executive functioning of the frontal lobes, thinking, planning among others, that which makes us human, are often reduced by huge and crippling amounts.

As much as 30 years can be wiped out after a single course of ECT, (6 treatments), and there is a rising amount of research showing the newer brief and ultra-brief, electrical charges cause as much damage as their predecessors, unilateral or not. This information is readily available but is shuffled under the table when `consent’ time comes. (Sackheim 2007)

You write about Dr. Josh Geffen. I saw him on the SBS Insight program. I have seen many such as he. Reasonable, personable and lying through his teeth.

[Geffen] says, a mixture of the common side effect of peri-treatment amnesia – loss of memory of the period around treatment – as well as the rarer retrograde amnesia, which is the loss of memory for “weeks, months, even years” before being treated. “With modern techniques, the peri-treatment amnesia is less severe and retrograde amnesia is even rarer,” he, [Geffen], says.

Permanent retrograde, anterograde amnesia and cognitive dysfunction are NOT RARE following ECT. At least 1:2 people will have permanent damage. (Sackheim 2007)

I have recently studied a survey done in the UK by `Daily Strength’. Of 483 replies, 204 reported that ECT did not work for them; 195 recorded that it `Worked or was Somewhat Helpful’. Call it 50% each. Complaints of memory loss were 103 in the `not worked’ group = approx. 50%; In the Worked/Somewhat Helpful, 87 complained of Memory loss = approx 45%. The total for all was, from 483: 204 = 45% people had specified memory loss as an issue. (Around 1:2) There were two other groups noted, an ambiguous group where there was not enough evidence to show whether the procedure had affected their depression/schizophrenia/other. 33% of those also complained of memory loss.

Another major feature was that 20-40% of people complained of bad emotional experiences with ECT. Rape, violation, helplessness, humiliation, and de-personalisation are just a few. (Lucy Johnstone 1999)

Psychiatrists claim there is no physical evidence for brain damage and use scans performed during and shortly after ECT. At that time the brain is still swollen. It is not until later that the cells whose blood supply is cut off by the swelling of the injured brain, die, leaving shrinkage across the entire brain surface. This process takes time and the psychiatrists are well aware of that. Neurologists commonly find that in later scans the brain atrophy from ECT is significant. There may also be evidence of small infarcts, (strokes) deep in the tissues.

Post-mortems typically display evidence of massive pinpoint bleeds across the brain surface, typically worse in the temporal and frontal lobes, as well as the scars from the infarcts. I have yet to see ANY ECT psychiatrists refer anyone for neuropsychological assessment post treatment. (Neurophsychology was developed to ascertain the type and degree of cognitive damage.) Interestingly the results of those I have seen describe the exact symptom set as other Traumatic Brain Injuries and lead to the same future deficits.

Studies in the UK , (1998, 2003, 2005, 2008 and others), have documented these issues.

I have seen people so damaged they don’t know how badly they are damaged. These are the people who are “slowed up in thinking and acting, they are dull, at times completely lacking in emotional expression or display and showed a striking reduction in interest and driving energy.”

Then we come back to Josh Geffen. On the SBS `Insight’ program he presented a woman called Natalie, who stated she had lost 30 years of her memory for her husband and children, whom he had been shocking for years.

Having worked in one of the old mental hospitals, the more I looked at her, the more uncomfortable I became. Something was very amiss. She was quite bland as she told of her 30 year memory loss. Her son was clearly upset when he said it was difficult for him that his mother didn’t know who he was. She was not obviously concerned. (If it was me I’d be screaming the place down). She was, as I described above, slowed, unconcerned, and lacking in emotion.

I saw almost identical signs at the old hospital of people who had had massive courses of ECT as well as many who had had lobotomies. A neurologist friend of mine agreed with me. This lady appears very severely brain damaged. The fact that Geffen presented a badly damaged patient whom he was/is still shocking as an advertisement for the value of ECT was totally cynical. He has rendered her less than human. In his arrogance perhaps he didn’t think anyone would notice.

Of course Geffen didn’t bother to tell us that memory is not a different and localised part of the brain. If she has lost 30 years of memory she has lost a lot more than that. In fact she no longer works as a qualified nurse but as an `attendant’’ in a nursing home.

A woman, Peggy Salter, in the USA in 2005, successfully sued her doctor and the hospital where she received ECT. She, also a highly qualified nurse, had lost all memory of her professional training and the raising of her children. She was found to be permanently disabled and received a jury award of $635,000. She was 60 years old. `Natalie’ appeared to be under 50. She could have another 40 years to live.

I hope Natalie’s family see this.

The claim of the `life saving’ aspects of ECT in that it saves people from suicide. There is no evidence that this is the case. ECT does not have an effect on completed suicides beyond the actual treatment time where highly suicidal people are confined. Suicide is four times more likely in ECT recipients during the first year following ECT. In the long term, over a year +, there is no difference between ECT patients and non ECT patients.

Loss of function, even temporarily, in the brain is caused by damage. It’s found in athletes in impact sports, road accident victims, as a result of fights and physical abuse. It’s called Traumatic Brain Injury. Unlike these other examples which are considered unfortunate/accidental, ECT machines are purpose-built to cause brain damage. No matter what you want to believe, this is its action. From the very beginning this has been documented. And it is repeated over weeks and months on end. After three head injuries footballers in the USA may not play for the rest of the season. ECT can cheerfully be repeated every other day for 20, 40, 66 treatments!

“Bilateral ECT is associated with greater cognitive impairment, but these effects vary from patient to patient.” So we’re not talking about no cognitive impairment, just lesser. Greater or lesser it’s still damage. In Australia there are no checks and balances on the use of ECT generally. Perhaps that’s why we have the highest per capita use of this treatment in the world.

“Geffen has been immersed in this world of ECT for more than 15 years”, and at $250 – $500 per treatment, (he cited 60 treatments a week on `Insight’) we are looking at an income of approximately $15,000 to $30,000 a week.) I don’t think he would be too willing to give that up, do you?

Now let’s see about the small electric current. The psychiatrists, description, `A series of brief, low-frequency electrical pulses prompt a convulsion’. What they don’t tell the patient is that the specifications for the Thymatron (from Somatics Inc), allows for from 150 – 450 volts in 140 pulses per second for 5.3 seconds. It’s the pulses that are brief but there are an awful lot of them.

The person is under anaesthesia before the treatment is applied, and the muscle relaxant reduces the intensity of muscular spasms. Unfortunately the anaesthesia itself makes the brain less able to convulse so more electricity has to be used to produce a convulsion. More power = more damage. In any case the psychiatrist will `titrate’, i.e. build the level of power, giving more and more shocks until a `seizure threshold’ is found. The doctor will then increase the power needed for the convulsion 2.5 times higher. This is standard procedure, at least under research terms. Individual unsupervised doctors may, and often do, increase the power by up to 400 times the basic level.

Secondly, there is ample evidence that permanent damage to some degree is almost universal. The claim that because of the anaesthesia `ECT carries a small degree of risk.’ What sort of risk? The psychiatrists claim 1:10,000 death rate. Unfortunately, particularly for older people, this is not true. Figures taken from the compulsory reporting of ECT outcomes in the US, California, Texas and Massachusetts, indicates that the figure comes down to 1:180-200 for 60+ and 1: 6-800 generally. (Read and Bentall 2010)

SO. Does it work?

No it doesn’t. In fact for the 30-60% of recipients who get relief of their symptoms during the actual treatment, 40% of any improvement will be lost after 10 days. (Prudic, 2003) At one month most will have relapsed. By six months virtually all will have relapsed. I know the ECT bio-psychiatrists claim miraculous improvement in 80-90% of their patients. Indeed, in some studies which used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale as a basis of their assessment of improvement, (standardised over many years), patients were given the questionnaire, firstly by their doctor where they recorded the 80-90% improvement.

However, when the same patients are given the same questionnaire by a fellow patient the improvement rating drops to 30%, a discrepancy of 60%. In research terms this anomaly is called the `intimidation factor’. Not that the doctor is necessarily abusive in any way, but his/her patients are eager to give the doctor what he/she wants to hear. In fact with manipulation of figures, types of scoring can indicate a mere 16% will improve. The short lived phenomenon is dealt with by prescribing `maintenance’ ECT. This means that every time the brain tries to heal itself it gets another blast. In 1998 a study in Manchester, UK, found that the most damaging use of ECT is the `maintenance’ ECT at once a week, a fortnight, a month. It will be able to be stretched out when the individual no longer has the capacity to be depressed, or anything else.

Ask Josh what he thinks of ECT for children.

Another claim to deal with this issue is to advise the patient that they will have to go back on the anti-depressants, (that failed to work before ECT and is why they are having ECT at all), in order to maintain their remission. Bollocks.

The anti-depressants don’t work in 80% of people, the `chemical imbalance in the brain’ nonsense is now recognised as nonsense. NO science supports that. It was a marketing strategy to sell Prozac.’

So we’re now expected to believe:

“It is tempting to speculate that ECT might act to rebalance” specific brain activity” . I. Reid, Aberdeen

…ECT works by “turning down” an overactive connection between areas of the brain causing depression. Incredibly, the authors claim electric shock may restore the brain’s natural chemical balance. Professor Ian Reid from the University of Aberdeen, and colleagues

“The reduction of intelligence is an important factor in the curative process… the fact is that some of the very best cures that one gets are in those individuals whom one reduces almost to amentia (feeble-mindedness).

In 1942, psychiatrist Dr. Abraham Myerson said: …” (translated from the French original)***

…the procedure does induce seizures, but they’re not painful and don’t cause convulsions…”(?)

“…As an effective and lifesaving treatment, it rates right up there with the discovery of penicillin…

“…has seen ECT help fight depression and prevent many suicides.” (No, as we’ve seen)

Dr. Niza Lahda, psychiatrist in St. John’s, Canada.

…he did not think there was any organic pathology in the brains of the mentally ill, but rather that their neural pathways were caught in fixed and destructive circuits leading to “predominant, obsessive ideas”.[n 11][74] As Moniz wrote in 1936:

[The] mental troubles must have […] a relation with the formation of cellulo-connective groupings, which become more or less fixed. The cellular bodies may remain altogether normal, their cylinders will not have any anatomical alterations; but their multiple liaisons, very variable in normal people, may have arrangements more or less fixed, which will have a relation with persistent ideas and deliria in certain morbid psychic states.[75]

For Moniz, “to cure these patients”, it was necessary to “destroy the more or less fixed arrangements of cellular connections that exist in the brain, and particularly those which are related to the frontal lobes”,[76] thus removing their fixed pathological brain circuits.

Moniz, 1936 (This is old, but the others are saying the same thing today.)

Current ECT promoters claim that the introduction of oxygen and anesthesia made ECT safe: “nothing equal to it in efficacy or safety in all of psychiatry”. Max Fink quoted in Boodman, SG, Shock therapy: It’s back, The Washington Post, September 24 1996, Page Z14. (Older people don’t do well with anaesthesia. If this is the best, God help us with the rest!)

“[it] rewires the brain”

“…not a treatment from the dark ages – it does not do the brain any harm”

Dr. Paul Skerritt, AMA Psychiatrist.

“…It is thought that the seizure `resets’ the brain.

…The reason why this treatment is so effective is still unclear. The brain functions using electrochemical messages, and it is thought that ECT-induced seizures `interrupt’ these messages.

Better Health Channel State Government Victoria, Department of Health last updated 2013

“The brain functions through complex electrical and chemical processes, which may be impaired by certain types of mental illness. It is believed ECT acts by temporarily altering some of these processes thereby returning function towards normal.” Electroconvulsive Therapy [ECT], Information for patients and Their Family. Reproduced with permission from “Electroconvulsive Therapy An Australian Guide”, eds JWG Tiller and RW Lyndon, Australian Postgraduate Medicine, 2003

The apparent paradox develops, however, that the greater the damage, the more likely the remission of psychotic symptoms…it has been said that if we don’t think correctly, it is because we haven’t `brains enough’. Maybe it will be shown that a mentally ill patient can think more clearly and more constructively with less brain in actual operation.”

Walter Freeman MD 1940s

Have a look at this one:

“shock treatment was not harmful, and although it might cause some limited memory loss, it only eliminated unhappy or depressing memories, and that Mr. Akkerman’s full memory would be restored in a short time but that he would no longer feel depressed.” Psychiatrist, 2001

(Mr. Akkerman lost his memory for most of the events of his life. He no longer recognised or knew his wife. He no longer recognised or knew his two teenaged children. He no longer knew or recognised his parents. His brother, who was a close companion and best friend in his childhood years, was a stranger. Mr. Akkerman had not recovered these memories.

Abilities lost included playing and writing music (he played professionally for years) and toured with the US Navy band. Prior to the shock treatment, Mr Akkerman was employed in a supervisory position with a non-profit foundation. After the shock treatment, he was unable to remember what he did in his job, did not know how to perform the duties of his job, and no longer knew the people he formerly worked with.

I didn’t think a 450 volt, with a 140 per second electric pulse through the brain could be that delicate and discerning that it only did away with `bad’ memories.

I wouldn’t insult your intelligence by expecting you could believe any of this rubbish, so I have listed some studies that might interest you. After all, once we have real science, we can move on from superstition and fanciful ideas.

REFERENCES:

Adverse psychological effects of ECT: Lucy Johnstone; Journal of Mental Health 1999

Shock Treatment: Efficacy, Memory Loss, and Brain Damage – Psychiatry’s Don’t Look, Don’t Tell Policy: Richard A Warner; 2005

The Sham ECT Literature: Implications for Consent to ECT: Colin A Ross, MD; 2006

Memory and Cognitive effects of ECT: informing and assessing patients: Harold Robinson & Robin Pryor; 2006

The Effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy: A literature review: John Read and Richard Bentall; 2010 (John Read was the `expert’ invited via a video link to the UK by the SBS `Insight’ program in October. He was shouted down in a disgraceful display by the 4 psychiatrists present during the program. Josh Geffen, Paul Fitzgerald, Colleen Loo and another guy. I was ashamed for my countrymen.)

MIND The Mental Health Charity 2001: A survey of people’s experiences of Electroconvulsive therapy ECT

Electroshock: scientific, ethical and political issues: Peter Breggin; International Journal of risk and safety in medicine 11 (1998)

“The Cognitive Effects of Electroconvulsive Therapy in Community Settings,” 2007) ..Harold Sackheim et al

ENJOY

Deirdre Oliver: deeeo42@yahoo.com.au NEW KNOWLEDGE IS SO EXCITING!

I myself had 12 rounds of ECT two years ago. My memory after having the procedures done is still horrible. I forget what I say to people sometimes, and I forgot a lot of things that happened to me in the psych ward.

The sad thing is, is that while I was waiting to get my ECT in the waiting room, there were ELDERLY people waiting to get the treatment. That is a really sad thing to witness. I reckon ECT should be banned in Australia!

I’ve not long finished Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine which she opens with a chilling account of Ewen Cameron’s use of extensive electroconvulsive therapy coupled with hallucinogenics, sensory deprivation and overload etc. in collusion with the CIA. Interesting to know that it is used today, in Australia (albeit a little more above-ground).